The United States and Israel combined are home to an estimated 80% of the world’s Jews. The new survey of Israelis, together with Pew Research Center’s 2013 survey of U.S. Jews, can be used to compare the world’s two largest Jewish populations.

Jews in the U.S. and Israel have deep connections. Majorities of Israeli Jews feel they share a common destiny with U.S. Jews and have either “a lot of” or “some” things in common with U.S. Jews. And most think that, overall, American Jews have a good influence on Israeli affairs. For their part, most U.S. Jews say they are either very or somewhat emotionally attached to Israel and that caring about Israel is essential or important to what being Jewish means to them. More than a third of Israeli Jews have traveled to the U.S., and a similar share of American Jews have been to Israel.

At the same time, however, Jews from the United States and Israel have differing perspectives on a range of political issues concerning the State of Israel and the peace process. While Israeli Jews are skeptical that Israel and an independent Palestinian state can peacefully coexist, most American Jews are optimistic that a two-state solution is possible. On the controversial issue of the continued building of Jewish settlements in the West Bank, the prevailing view among Israeli Jews is that settlements help the security of Israel. By contrast, American Jews are more likely to say the settlements hurt Israel’s own security.

The two communities also differ over the U.S. government’s level of support for Israel. The most common view among Israeli Jews is that the U.S. is not supportive enough of Israel, while the most common opinion among American Jews is that the level of U.S. support for Israel is about right.

Most Israeli Jews describe their ideology as in the center (55%) or on the right (37%) within the Israeli political spectrum. Just 8% of Israeli Jews say they lean left. American Jews, meanwhile, generally describe their ideology as liberal (49%) or moderate (29%) on the American political spectrum, while about one-in-five (19%) say they are politically conservative.

These two political spectrums (liberal/moderate/conservative in the U.S. and left/center/right in Israel) represent different constellations of views on political, economic and social issues in each country. Nevertheless, in both Israel and the U.S., religious Jews tend to lean more to the right, while more secular Jews are centrist or liberal.

When it comes to opinions about the peace process, settlements and U.S. support for Israel, both Israeli Jews and American Jews express a wide range of views. But on the whole, Israeli Jews are more deeply divided along ideological lines than are American Jews. One way to see the magnitude of these ideological differences in each society is the gap in opinions between Jews on each end of the political spectrum. For example, among American Jews, 43% of those who describe their political opinions as conservative say a peaceful two-state solution is possible, compared with 70% of those who say they are liberal – a gap of 27 percentage points. Among Israeli Jews, 29% of those on the political right say a peaceful two-state solution is possible, compared with 86% on the left – a 57-point gulf.

While they follow the same ancient religious tradition, U.S. Jews and Israeli Jews also differ in their relationship with Judaism as a religion. Virtually all Israeli Jews say they are Jewish when asked about their religion, even though nearly half of them also identify as secular Jews and one-in-five do not believe in God. But fully 22% of American Jews – including about one-third of those in the Millennial generation (adults born in 1981 or later) – do not identify as Jewish on the basis of religion. Instead, they say they have no religion but they have Jewish parents and consider themselves Jewish in other ways, such as by ancestry or culture.

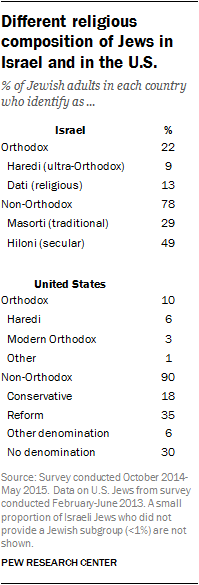

Many American Jews identify with Jewish denominations that do not have a major presence in Israel, such as the Conservative and Reform movements. And Orthodox Jews make up a bigger share of adults among Israeli Jews than American Jews (22% of Israeli Jewish adults are Orthodox, compared with 10% of American Jews).

Overall, Jews in Israel are more religiously observant than Jews in the United States. In part, these differences reflect the higher share of Israeli Jews who are Orthodox. But even among the non-Orthodox, American Jews are less religious by several measures of observance, such as frequency of synagogue attendance, certainty of belief in God and rates of keeping kosher at home or attending a Seder. For example, nearly two-thirds of Israeli Jews say they keep kosher at home, compared with about a quarter of Jewish Americans.

This chapter takes a deeper look at connections and similarities between Israeli Jews and U.S. Jews as well as some areas of divergence between the two groups, beginning with religious differences between the two communities.

Israeli Jews more observant than U.S. Jews

Share of Jews who are Orthodox is twice as large in Israel as in the U.S.

Although they share the same religion, Israeli Jews and U.S. Jews often do not practice Judaism the same way. Israeli Jews themselves range from very religious to secular, but they are, on average, more religiously observant than American Jews.

One driver of the religiosity gap between Israeli Jews and U.S. Jews is the fact that Orthodox Jews make up about one-in-five Jews in Israel (22%) but only one-in-ten Jewish adults in the United States (10%). In both countries, Orthodox Jews tend to be far more religiously observant than other Jews.

In this report, Israeli Jews are categorized into four main subgroups – Haredi (often translated as “ultra-Orthodox”), Dati (“religious”), Masorti (“traditional”) and Hiloni (“secular”). Nearly all Israeli Jews self-identify with one of these four identity categories. Both Haredim and Datiim are classified as Orthodox in this report. (For more details on Orthodox Jews in the U.S., see “A Portrait of American Orthodox Jews.”)

In the U.S., meanwhile, Jews commonly identify with more formal, institutionalized movements, often called “Jewish denominations” or “streams” of Judaism. About half of U.S. Jews identify with either the Conservative (18%) or Reform (35%) movements, and roughly 6% belong to smaller streams, such as the Reconstructionist and Jewish Renewal movements. An additional 30% of U.S. Jews do not identify with any particular stream or denomination of Judaism.

For this reason, it is perhaps best to compare Orthodox U.S. Jews to Orthodox Israeli Jews and, separately, to compare all non-Orthodox Jews in the two countries.

In both Israel and the U.S., Haredim are analogous groups. Haredim in both countries tend to live in tight communities and to divide themselves into numerous small groups, including many different Hasidic sects as well as Yeshivish (also known as Lithuanian Orthodox) communities. And in both countries, Haredim tend to view their strict adherence to the Torah’s commandments as largely incompatible with secular society.

To some extent, Datiim in Israel are analogous to Modern Orthodox Jews in America. But Masortim and Hilonim do not have direct equivalents in the U.S., even though the term “Masorti” is the official name of the Conservative Jewish movement in Israel.

To explore the overlap (or lack thereof) between American Jewish denominations and Israeli Jewish identity, the survey asked Jews in Israel about common streams within Judaism around the world. Acknowledging that some of these streams may not be familiar to them, the survey asked respondents, using the transliterated English terms, whether they identify with any of these streams – Orthodox, Conservative, Reform or no particular stream. (See survey topline results for full question wording.)

Fully half of Israeli Jews say the international stream of Judaism they identify with is Orthodox. In addition to the vast majority of Haredim and Datiim, roughly two-thirds of Masortim and about one-in-five Hilonim say they identify with the Orthodox stream, even though Masortim and Hilonim are commonly considered non-Orthodox groups. In some cases, their identification with Orthodox Judaism may have less to do with their personal religious beliefs or practices and more to do with a recognition of Orthodoxy as the oldest and most traditional kind of Judaism, or perhaps with Orthodox rabbis’ key role in Israeli public life.13 The second most common choice among Israeli Jews is “no particular stream” (41%). Relatively few Israeli Jews identify with either Conservative (2%) or Reform (3%) Judaism.

Israeli Jews more likely than U.S. Jews to observe Jewish rituals and practices

Overall, Israeli Jews display more religious involvement than U.S. Jews on several measures. Roughly a quarter (27%) say they attend religious services at least weekly, more than double the share of American Jews who say the same (11%). Israeli Jews also are somewhat more likely than U.S. Jews to say religion is very important in their lives (30% vs. 26%), and considerably more likely to say they believe in God with absolute certainty (50% vs. 34%) and that they believe God gave Israel to the Jewish people (61% vs. 40%).

Additionally, Jews in Israel report more frequent participation in specific Jewish practices than do Jews in the U.S. For example, 56% of Israeli Jews say someone in their home always or usually lights Sabbath candles on Friday night, compared with 23% of U.S. Jews who say the same. Roughly six-in-ten Jews in Israel (63%) say they keep kosher in their home, nearly three times the share of American Jews who do this (22%). Israeli Jews also are more likely than U.S. Jews to say they hosted or attended a Seder for Passover (93% vs. 70%) and fasted all day on Yom Kippur (60% vs. 40%) in the last year.

While the larger share of Orthodox Jews in Israel accounts for some of these differences, it does not always fully explain the gaps. By some measures, Orthodox Jews in Israel are even more religious than U.S. Orthodox Jews, and non-Orthodox Israelis show higher levels of religious engagement than their U.S. counterparts.

Even self-identified secular Jews in Israel (Hilonim) have higher rates of observance of certain Jewish beliefs and practices than do U.S. Jews overall. For instance, a third of Hilonim (33%) say they keep kosher in their home, while 22% of U.S. Jews overall do this (including just 7% of Reform Jews). And 87% of Hilonim say they attended a Seder last Passover, higher than the share of all U.S. Jews who observed this ritual (70%).

One possible explanation for the differences in levels of religious practice across the two countries is that Jewish observance is more ingrained in daily life in Israel than it is in the U.S. For example, many Israeli businesses close early on Friday afternoon before the start of the Sabbath, kosher food is more widely available in Israel, and major Jewish holidays are generally Israeli national holidays (whereas American Jews may have to miss normal business or school days to observe Jewish holidays).

But when it comes to standard measures of religious commitment, almost no Hilonim (2%) say religion is very important in their lives, and a majority say they never go to synagogue (60%). Virtually all Jewish subgroups in the U.S. are more religious than Hilonim by these measures.

In fact, the strongly secular habits of many Israeli Jews add a layer of nuance to the comparison with U.S. Jews, who by some measures are more likely to display a moderate level of religious observance. While Israeli Jews overall are more likely than U.S. Jews to attend religious services weekly, they also are more likely to say they never attend synagogue (33% vs. 22%). Roughly a third of American Jews (35%) say they attend synagogue “a few times a year, such as for High Holidays,” far higher than the comparable figure for Israeli Jews (14%).

There are also some demographic differences between Israeli and American Jews. While Israeli Jewish men overall show higher measures of religious commitment than women, the opposite is true among U.S. Jews by some measures. For example, among Israeli Jews, men are more likely than women to say religion is very important in their lives (35% vs. 25%), but among U.S. Jews, women are more likely to say this (29% vs. 22%).

U.S. Jews are older, more educated than Israeli Jews

U.S. Jews, who have a median age of 50 (among adults), are somewhat older than Israeli Jews (median age of 43).

But perhaps the more striking demographic difference between the two groups is that, overall, American Jews have considerably more formal education than their counterparts in Israel. This reflects the fact that American Jews are a small minority (roughly 2% of the total U.S. population) at the high end of the U.S. educational spectrum, while in Israel, Jews make up roughly 80% of the total adult population and are more evenly distributed across the spectrum of educational attainment.

A majority of American Jews (58%) have a college degree, including 28% who have a postgraduate degree. Among Israeli Jews, a third of adults have finished college (33%) and roughly one-in-ten (12%) have a postgraduate degree. Israeli Jews’ rates of attainment are roughly similar to U.S. adults overall, 29% of whom have finished college (including 10% who have a postgraduate degree).

While very few American Jewish adults (2%) have not finished high school, fully a quarter of Israeli Jewish adults say they did not complete high school.

Close connections between Jews in U.S. and Israel

Despite the differences in affiliation and other demographic characteristics between Israeli and American Jews, strong bonds between the two communities are readily apparent. A sizable minority of Jewish Americans (43%) say they have traveled to Israel, comparable to the share of Israeli Jews who have made the lengthy trip to the United States (39%).

Even many U.S. Jews who have not traveled to Israel feel an emotional attachment to the Jewish state. About seven-in-ten Jews in the U.S. say they are either very (30%) or somewhat (39%) attached to Israel, while more than eight-in-ten say caring about Israel is either an essential (43%) or important (44%) part of what being Jewish means to them personally.

The connection is also felt in the opposite direction. About two-thirds of Israeli Jews (68%) say they have at least some things in common with U.S. Jews, including 26% who say they have “a lot” in common with Jewish Americans. Three-quarters of Jews in Israel (75%) feel they share a common destiny with U.S. Jews in at least some way, including 28% who say they feel this way “to a great extent.” And 69% say a “thriving diaspora” is necessary for the long-term survival of the Jewish people (although even more – 91% – say a Jewish state is necessary for the long-term survival of the Jews).

Moreover, Israeli Jews are far more likely to say U.S. Jews have a good influence on the way things are going in Israel (59%) than to say U.S. Jews are having a bad influence (6%). About three-in-ten Israeli Jews say Jews in the U.S. have neither a good nor bad influence on Israeli affairs.

In the United States, younger Jews express lower levels of emotional attachment to Israel than do older Jews. Among Jews in Israel, however, the new survey finds few, if any, significant differences by age in attitudes toward U.S. Jews.

Israeli and American Jews also feel similar connections to the Jewish people more broadly defined. More than nine-in-ten in both groups say they are proud to be Jewish. Three-quarters or more of Jews in both countries say they feel a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people (88% in Israel, 75% in the U.S.). And more than half of Jews in Israel (55%) and a solid majority in the United States (63%) say they feel a special responsibility to care for fellow Jews in need around the world.

Different perspectives on the peace process, settlements and U.S. support for Israel

Despite their connections and shared attachment to the Jewish state, Israeli Jews and U.S. Jews have very different perspectives on some controversial political issues in Israel.

American Jews, at the time of the 2013 survey, were more optimistic about the prospects for a two-state solution than were Israelis when they were polled in 2014-15.14 Most U.S. Jews (61%) said in 2013 that they believe a way can be found for Israel and an independent Palestinian state to coexist peacefully. Fewer Israeli Jews (43%) take this view, while 45% say a two-state solution is not possible and 10% volunteer that it depends on the situation.

U.S. Jews and Israeli Jews also differ on the impact of Jewish settlements in the West Bank. While a plurality of Jews in Israel (42%) say the continued building of these settlements helps the security of Israel, only 17% of U.S. Jews agree with this view. By contrast, in the U.S., a plurality of Jews (44%) say the settlements hurt Israel’s own security interests; fewer Israeli Jews (30%) take this position.

About half of Israeli Jews (52%) feel their country should be getting more support from the U.S. government, while roughly a third (34%) say the amount of support the U.S. gives Israel is about right. Among Jewish Americans, these figures are flipped: Roughly three-in-ten (31%) say the U.S. does not support Israel enough, while more than half (54%) say U.S. support for Israel is about right (as of 2013).

On all of these questions, Israeli Jews’ views vary widely based on political ideology. The large segment of Israeli Jews on the political right are far more likely than the smaller number on the left to say a two-state solution is not possible and that settlements help Israel’s security.

Self-described politically liberal and conservative American Jews also offer differing opinions on the two-state solution and the impact of settlements on Israel’s security. But on these two questions, the difference in opinion between Jews on either end of the political spectrum in the U.S. is smaller than the ideological divide on these issues in Israel.

While American Jews are more optimistic than Israeli Jews about the possibility of a two-state solution, they are considerably less likely than Israeli Jews to say the Israeli government – controlled by a center-right/right-wing coalition for the last several years – is making a sincere effort to achieve peace with the Palestinians (38% vs. 56%). Like Israeli Jews, relatively few American Jews (12%) say the Palestinian leadership is making a sincere effort to achieve peace.

Orthodox Jews in both countries are about equally likely to say the Israeli government is making a sincere effort to bring about a peace settlement. But non-Orthodox Jews in Israel are considerably more likely than their American counterparts to say the Israeli government genuinely seeks a peace settlement (55% vs. 36%).

Once again, in both countries, Jews on either end of the ideological spectrum offer differing opinions on the sincerity of both parties in the peace process (i.e., Jews on the left are less likely than those on the right to say the Israeli government is sincerely pursuing peace and more likely to say Palestinian leaders are sincere). But the ideological divide between left- and right-leaning Jews in Israel is deeper than the divide between liberal and conservative American Jews. Among Israeli Jews on the left, 23% say the Israeli government is making a sincere effort to achieve peace, compared with 70% of those on the right (a 47-point gap). There is a 31-point gap between liberal (27%) and conservative (58%) U.S. Jews on this question.

When it comes to these political issues, one key demographic difference between Jews in the two countries involves age. Younger American Jews (that is, those between the ages of 18 and 29) are more likely than their elders to take a more liberal stance on political issues involving Israel – e.g., more likely to say that a two-state solution is possible and that the U.S. is too supportive of Israel. However, there are few significant differences by age among Israeli Jews.

Perhaps one of the strongest indications that Israeli Jews and U.S. Jews have different perspectives on life in Israel is the question of the biggest long-term problem facing Israel. In response to an open-ended question, roughly equal shares of Israeli Jews cite economic issues (39%) and security (38%) as the biggest long-term problems facing their country. But among U.S. Jews, very few (1%) mention the economy as the biggest long-term problem facing Israel, while fully two-thirds of Jewish Americans cite security (66%). Similar shares in both countries – about one-in-six – say social, religious or political issues are the biggest problem Israel faces.

U.S. Jews have more social connections with members of other religions

American Jews are much more likely than Israeli Jews to have close friendships with people of other faiths, and intermarriage is also comparatively common among non-Orthodox U.S. Jews. This no doubt reflects the fact that Jews make up only about 2% of all U.S. adults – a far different religious environment than in Israel, where Jewish adults make up roughly 80% of the population. But it may also speak to the integration of Jews into the proverbial melting pot of American society.

Among U.S. Jews who are married, 44% say they have a spouse who is not Jewish. Just 2% of Israeli Jews who are married have a spouse who is a member of another religious group or religiously unaffiliated.15

American Orthodox Jews, however, look more like their Israeli counterparts. Very few married Orthodox Jews in the U.S. (2%) say they are married to a non-Jew. Similarly, no Haredi or Dati Jews surveyed in Israel are in a religious intermarriage. Among non-Orthodox American Jews, half of those who are married say they have a non-Jewish spouse. By contrast, very few non-Orthodox Israeli Jews in a marriage (2%) say they have a spouse who is not Jewish.

U.S. Jews also are much more likely to have friendships with non-Jews: 98% of Israeli Jews say all or most of their close friends are Jewish, while only about a third of U.S. Jews (32%) say the same. Roughly two-thirds of Jewish Americans say just “some” or “hardly any” of their close friends are Jewish.

Even among Orthodox Jews in the United States, friendships at least sometimes extend beyond the Jewish community; 84% of American Orthodox Jews say all or most of their friends are Jewish, but 15% say at least some of their friends are not Jewish. By comparison, virtually all Israeli Orthodox Jews (99%) say all or most of their friends are Jewish.

Jewish Americans are more likely than other religious minority groups in the U.S. to have close friends from outside their religious group. Previous Pew Research Center surveys have found that a majority of U.S. Mormons (57%) and roughly half of American Muslims (48%) say all or most of their friends share their faith.

Differing ideas on what is essential to Jewish identity

Religious practices, political views and social circles are not the only ways in which Jews in Israel differ from Jews in the U.S. Indeed, American Jews express different views from Israeli Jews about what it means to be Jewish.

Both surveys asked respondents about a series of possible “essentials” of personal Jewish identity. While most Israeli Jews and U.S. Jews say remembering the Holocaust is essential to what being Jewish means to them, personally, there are bigger gaps on several other questions.

In general, more American Jews are inclined to see personal and social responsibility as essential to their Jewish identity. For instance, U.S. Jews are more likely than Israeli Jews to say leading an ethical and moral life is essential to their Jewish identity (69% vs. 47%); the same is true of working for justice and equality (56% vs. 27%). Jewish Americans also are more likely than their Israeli counterparts to emphasize intellectual curiosity (49% vs. 16%) and a good sense of humor (42% vs. 9%) with respect to their Jewish identity.

Israeli Jews, by contrast, are more likely than U.S. Jews to see observing Jewish law as an indispensable part of what being Jewish means to them (35% vs. 19%).

In addition to the eight specific items mentioned in the survey (remembering the Holocaust, observing Jewish law, etc.), respondents in both countries were asked if there is anything else that is essential to what “being Jewish” means to them, personally. This open-ended question, which respondents were asked to answer in their own words, drew a relatively small number of responses in the U.S. survey – most American Jews (62%) did not describe any further attributes of their Jewish identity.

By contrast, nearly all Israeli Jews offered at least one additional essential element of their Jewish identity, and many offered more than one. The vast majority of Israeli Jews emphasize being connected with Jewish history, culture and community as central to their Jewish identity (93%). Specifically, 32% of Jews say having a sense of belonging to the Jewish community is essential to their Jewish identity. Roughly one-in-five Jews also mention having knowledge about one’s history and roots as being central to their Jewish identity.

A majority of Israeli Jews also cite being connected with one’s family (73%) as central to their Jewish identity. This includes roughly half (53%) who say passing on Jewish traditions to children is essential to what being Jewish means to them.

This large difference in open-ended responses between U.S. Jews and Israeli Jews may stem from several factors. Because of the difference in the social and political context between the United States and Israel, Israeli Jews may have been culturally predisposed to talk at greater length than Americans about their Jewish identity. Also, the Israel survey was conducted in person, which may have encouraged respondents to be more engaged with this open-ended question than the American respondents, who were interviewed on the phone. (For a full evaluation of how the mode of survey administration could have influenced the results of the study, see the methodology.)

Further, the questions about Jewish identity that preceded the open-ended question were originally designed for American Jews and used in the Israel survey to allow for comparisons between the two groups. Israeli Jews may have felt dissatisfied with the choices offered to them in the closed-ended questions, which led to more extensive responses in the open-ended question.

While U.S. and Israeli Jews may not always agree on what is essential to their Jewish identity, they generally concur on what does or does not disqualify a person from being Jewish. Both U.S. and Israeli Jews generally agree that someone can be Jewish even if he or she is strongly critical of the Jewish state (89% of U.S. Jews and 87% of Israeli Jews say this), works on the Sabbath (94% in U.S., 87% in Israel) or does not believe in God (68% in U.S., 71% in Israel).

Both groups are far less likely to say someone can be Jewish if that person believes Jesus was the Messiah (34% in U.S., 18% in Israel).

Regardless of Orthodox or non-Orthodox background, Jews in both countries take the same side on whether a person can be Jewish if he or she believes Jesus was the Messiah, works on the Sabbath or is strongly critical of the State of Israel. But when it comes to the question of whether a person can be Jewish if they do not believe in God, a much lower share of Orthodox than non-Orthodox Jews in Israel say this (48% vs. 78%). In the United States, majorities of both Orthodox (57%) and non-Orthodox (69%) Jews agree that a person can be Jewish even if he or she does not believe in God.

Among Jews in both the U.S. and in Israel, half or more (62% and 55%, respectively) describe their Jewish identity as primarily a matter of culture or ancestry.

Israeli Jews are somewhat more likely than American Jews to say being Jewish is mainly a matter of religion (22% vs. 15%). This gap is driven primarily by differences between Orthodox Jews in both countries; 60% of Haredim and Datiim in Israel say their Jewish identity is primarily about religion, compared with 46% of American Orthodox Jews who say the same, although considerable shares of both groups say being Jewish is a matter of both religion and ancestry/culture.

Overall, nearly a quarter of Jews in both countries (23% each) say their Jewish identity is a matter of religion and ancestry/culture.