The Mental-Health Consequences of Unemployment

Those who have been looking for work for half a year or more are more than three times as likely to be suffering from depression as those with jobs.

“Your whole life your job defines who you are,” Yundra Thomas told The New York Times two summers ago. “All of the sudden that’s gone, and you don’t know what to take pride in anymore.”

Unemployment is commonly understood as an economic problem, and inquiries into its nature tend to come from that perspective. Why do people struggle to find work even when jobs are available? What are the job prospects for those who have been unemployed for a long time? What policies, if anything, can Washington enact to help?

But, as Thomas is saying, unemployment often exacts a toll that goes beyond economic concerns to psychological ones. Humans, after all, are not robots, and the loss of a job is not merely the loss of a paycheck but the loss of a routine, security, and connection to other people.

A new poll from Gallup attempts to gauge the consequences of those losses and finds that "unemployed Americans are more than twice as likely as those with full-time jobs to say they currently have or are being treated for depression—12.4 percent vs. 5.6 percent, respectively." Moreover, for those who have been unemployed for 27 weeks or more (the "long-term unemployed," currently numbering 3.4 million people), the depression rate is 18 percent, nearly one in five.

Steve Crabtree, who wrote up Gallup's results, emphasizes that "the causal direction of the relationship ... is not clear from Gallup's data. It is possible that unemployment causes poor health conditions such as depression, or it could be that having such conditions makes it harder to land a job."

Or, if intuition will be allowed to supplement data, it could be a lot of both.

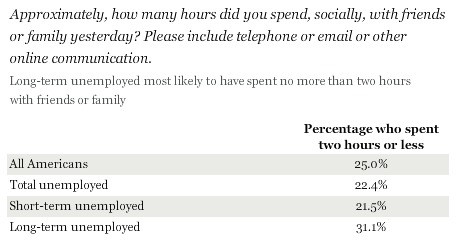

Crabtree cites a 2011 study by the Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University which found that long-term unemployed people were much more likely to report that they had spent two hours or less being social the previous day.

"Again," Crabtree writes, "these results don't necessarily imply unemployment itself causes these differences. It may be that unhappy or less positive job seekers are less likely to be able to get jobs in the first place—if, for example, employers are looking for more upbeat workers. It is also possible that those who spend less time with family and friends are therefore less able to draw on their social networks for employment leads."

Surely there are people out there who are accurately described by one of those possibilities. But it's all too easy to imagine a scenario in which all of these act together in a vicious cycle that mires a person in unemployment. That same Rutgers study found much higher rates of reporting "feeling ashamed or embarrassed" or "strain in family relations" for those for whom a loss of a job had had devastating financial consequences. As one reader wrote to The Atlantic in 2011, "I look at my peers who are getting married and having children and generally living life and it's depressing. They've got jobs, health insurance, relationships, homes; I don't even have a real bed to sleep on."

Would hanging out with friends and family be very appealing under such circumstances? Not to me, at least. From there, it's a pretty direct line to isolation, depression, the toll those will have on a job search, to more isolation, more depression, and on and on and on.

It gets worse: Crabtree notes a recent study that many people who find work after long periods of unemployment lose their new jobs within the year. Perhaps, he theorizes, their depression is causing them to miss work, and their employers aren't interested in waiting around for them to recover.