If you spend any time consuming right-wing media in America, you quickly learn the following: Liberals are responsible for racism, slavery, and the Ku Klux Klan. They admire Mussolini and Hitler, and modern liberalism is little different from fascism or, even worse, communism. The mainstream media and academia cannot be trusted because of the pervasive, totalitarian nature of liberal culture.

This belief in a broad liberal conspiracy is standard in the highest echelons of the conservative establishment and right-wing media. The Russia investigation is dismissed, from the president on down, as a politicized witch hunt. George Soros supposedly paid $300 to each participant in the “March for Our Lives” in March. (Disclosure: I marched that day, and I’m still awaiting my check.) What is less well appreciated by liberals is that the language of conspiracy is often used to justify similar behavior on the right. The Russia investigation is not just a witch hunt, it’s the product of the real scandal, which is Hillary-Russia-Obama-FBI collusion, so we must investigate that. Soros funds paid campus protestors, so Turning Point USA needs millions of dollars from Republican donors to win university elections. The liberal academic establishment prevents conservative voices from getting plum faculty jobs, so the Koch Foundation needs to give millions of dollars to universities with strings very much attached.

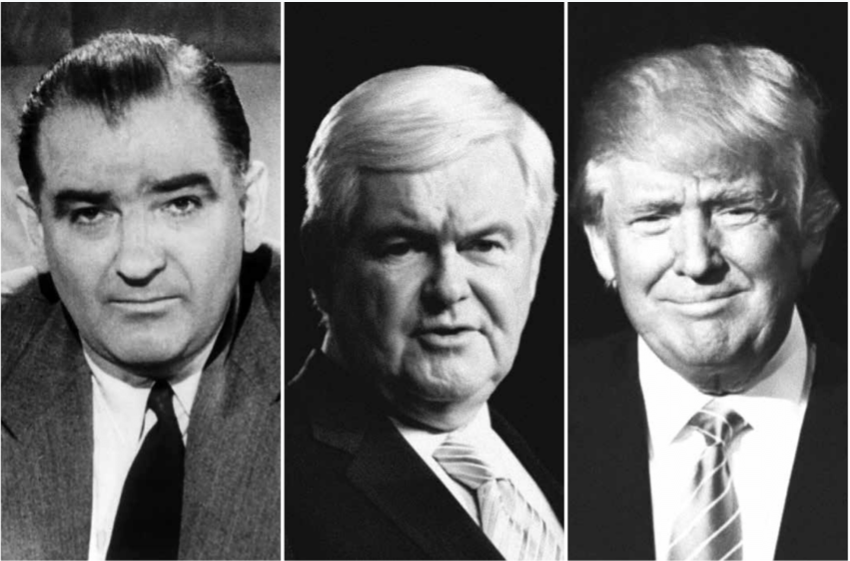

This did not begin with Donald Trump. The modern Republican Party may be particularly apt to push conspiracy theories to rationalize its complicity with a staggeringly corrupt administration, but this is an extension of, not a break from, a much longer history. Since its very beginning, in the 1950s, members of the modern conservative movement have justified bad behavior by convincing themselves that the other side is worse. One of the binding agents holding the conservative coalition together over the course of the past half century has been an opposition to liberalism, socialism, and global communism built on the suspicion, sometimes made explicit, that there’s no real difference among them.

In 1961, the American Medical Association produced an LP in which an actor opened a broadside against the proposed Medicare program by attributing to Norman Thomas, a six-time Socialist Party candidate for president, a made-up quote that “under the name of liberalism the American people will adopt every fragment of the socialist program.” Because these ideologies were so interchangeable in the imaginations of many conservatives—and were covertly collaborating to enact their nefarious agenda—this meant that it was both important and necessary to fight back through equally underhanded means.

One of the binding agents holding the conservative coalition together over the course of the past half century has been an opposition to liberalism, socialism, and global communism built on the suspicion, sometimes made explicit, that there’s no real difference among them.

The title of that LP? Ronald Reagan Speaks Out Against Socialized Medicine. The American left is used to waiting for liberals to finally get ruthless. Through the eyes of the right, they always have been.

Long before Fox News, conservatives began forming their own explicitly right-wing media landscape. Supporters of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal dominated the “mainstream” press, which meant that conservative dissidents needed a home. The conservative magazine Human Events was launched in 1944 as an alternative to what its cofounder, Felix Morley, believed was a stifling conformity in the American press. The same was true of the American Mercury in 1950, when under the ownership of William Bradford Huie the formerly social-democratic magazine moved to the right. “There is now far too much ‘tolerance’ in America,” Huie declared in the first issue of the new Mercury. “We shall cry a new crusade of intolerance . . . the intolerance of bores, morons, world-savers, and damn fools.”

Both Morley and Huie felt victimized by a liberal press establishment that stifled alternative voices—and, after all, liberals had the New Republic and leftists the Nation as journals of opinion—but their charge of mainstream “bias” was more complicated. One of the largest newspapers in the United States, the Chicago Tribune, owned by conservative businessman Robert McCormick, had militantly opposed the New Deal and American entry into World War II. Fulton Lewis Jr., a Washington, D.C.–based political journalist who was, by 1950, one of Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy’s biggest supporters, had one of the most listened-to radio programs in the country. And both Morley and Huie had had illustrious careers before launching their magazines. Morley won a Pulitzer Prize when he edited the Washington Post in the 1930s; Huie had a solid reputation as a freelance journalist. But they clung to the belief that dissenters from the liberal orthodoxy were being hounded out of media, which more than justified questionable acts, particularly on Huie’s part. Desperate to keep his magazine afloat, Huie sold the American Mercury in 1952 to far-right businessman Russell Maguire, who was closely tied to prominent anti-Semites and was one himself. Huie told a reporter at Time that he knew all about Maguire’s unsavory views, but believed his financial backing was necessary in order to ensure a conservative voice in American letters. “If I suddenly heard Adolf Hitler was alive in South America and wanted to give a million dollars to the American Mercury, I would go down and get it.”

Even more alarming to conservatives than the bias of the mainstream press was the number of liberals, radicals, and communists alleged to be in higher education. In a 1952 American Mercury article, a twenty-seven-year-old William F. Buckley accused liberal historians of a “conspiracy against giving the American people the facts” about Franklin Roosevelt, and claimed that they thus “betrayed the American people.” In his debut book, God and Man at Yale, published the year before, Buckley had dismissed academic freedom as a cynical shield wielded by left-wing faculty to protect themselves from the political consequences of their views; he advocated using the threat of withholding alumni donations as a weapon against the liberalism and leftism running amok in the academy. Buckley would soon become the gatekeeper of “respectable” conservatism by pushing back against the conspiratorial excesses of the John Birch Society. But he began his career by indulging in some of those rhetorical flourishes himself, along with a plan of action on how to fight back against the stranglehold of leftists on the academy.

Buckley was also one of McCarthy’s most vociferous defenders. Although popularly remembered today as a drunken punch line discredited by crusading journalists like Edward R. Murrow in the 1950s, McCarthy is actually an important figure in the development of American conservatism. Almost every major conservative journalist and politician in the 1950s defended him. Senator Barry Goldwater voted against McCarthy’s censure in 1954. Conservative radio pundit Fulton Lewis defended McCarthyism in his broadcasts even after the senator’s death. William F. Buckley was no exception: he went to the bat for McCarthy in the 1954 book McCarthy and His Enemies. Buckley applauded McCarthy for recognizing that “coercive measures” were necessary to enforce a new anticommunist “conformity.” While Buckley—unlike many of his peers—did distinguish between “the Liberals” and “the Communists,” he suggested that “atheistic, soft-headed, anti-anti-Communist liberals” were ultimately little better than communists, and by far a greater danger to American democracy than any supposed excesses of McCarthyism. And indeed, Buckley never abandoned his defense of McCarthy and repeatedly attempted to rehabilitate the senator in the eyes of the broader public. In 1999 he published a pro-McCarthy novel, The Redhunter, which incorporated large swaths of McCarthy and His Enemies almost verbatim.

Still, Buckley was comparatively moderate next to other conservatives, who suggested that the answer to the communist threat might be to adopt the communists’ own tactics. Fred Schwarz, an Australian-born doctor who founded the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade in 1953, wrote in his book You Can Trust the Communists (to be Communists) that liberals were effectively “protectors and runners of interference for the Communist conspirators.” Why? Because liberals resisted efforts to purge communists and their sympathizers from schools and universities, and insisted on pesky legal technicalities like the Fifth Amendment. “[O]rganization is the genius of Communism,” Schwarz continued, and so “an anti-Communist program needs organization.” Just as communists “operate through a great number of front organizations, each of which is tuned to some specific motivating dynamic,” so must “every religious, professional, economic, and cultural group” adopt this model to “organize an anti-Communist program.”

A full-blown Leninist approach was tempting, Schwarz wrote, but he preferred a decentralized organization based on “voluntary choice and free will.” Not all on the anticommunist right were so circumspect. Robert Welch, a wealthy retired candy manufacturer and right-wing activist, organized the John Birch Society in 1958 explicitly along the lines of what he called “international communism.” Welch wrote in the society’s founding document, The Blue Book, that this was simply a savvy political decision: the communist conspiracy was, after all, “incredibly well organized,” and “so well financed that it has billions of dollars annually just to spend on propaganda.” The Birchers would, like the communists, organize themselves into cells (or, as Welch preferred to call them, “chapters”), set up front organizations, and distribute propaganda (by which Welch meant conservative magazines and journals, including National Review, Human Events, and his own American Opinion). The goal was not to become a mere “organization” like the Democratic or Republican Parties, but to become a movement, in the same sense as communism or its close ideological ally, organized labor. And indeed, at its peak in the early 1960s the John Birch Society claimed around 100,000 members, more than the Communist Party USA at its height in the 1940s, easily making it the largest and best-organized group on the right. The Birchers’ on-the-ground presence certainly dwarfed the reach of the National Review, which in 1961 counted only 29,000 weekly subscribers.

One of the Birchers’ most prominent campaigns was a drive to impeach Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, who had presided over a Court that made dramatic rulings in favor of civil rights, ranging from establishing a right to birth control to abolishing mandatory school prayer to the greatest sin of all, desegregating public schools. In August 1963, Welch accused the civil rights movement of being a communist plot to create a “Soviet Negro Republic” in the South, with Martin Luther King Jr. as president, and blamed Brown v. Board of Education for poisoning race relations in America. “What we want to do,” Welch wrote in the Birch Society’s bulletin, “is to concentrate the whole opposition to what is happening in the South, and resentment of it, into one course of action: The Movement to Impeach Earl Warren.”

The conflation of communism and the NAACP was not accidental. Of all of the supposedly communistic liberal front groups, none drew conservative scorn more fiercely than the civil rights movement. William F. Buckley, who opposed the impeachment as a tactic against the Warren Court, nonetheless infamously wrote in 1957 that the “advanced” white race in the South was justified in taking “such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally,” in areas where “it does not predominate numerically.” His magazine, National Review, repeatedly suggested that the civil rights movement was communist inspired, riddled by communist infiltration, or composed of communist front organizations. Martin Luther King himself was suspect—National Review called him the “source of violence in others” in 1965.

Robert Welch, a wealthy retired candy manufacturer and right-wing activist, organized the John Birch Society in 1958 explicitly along the lines of what he called “international communism.”

King was far more radical than his sanitized popular memory today—he spoke out against American imperialism in Vietnam, called for a guaranteed basic income, and was murdered while visiting Memphis to support a strike by public-sector sanitation workers—but he was no doctrinaire Marxist-Leninist. “Communism forgets that life is individual,” he said in a 1967 speech, while also condemning capitalism for forgetting “that life is social.” These distinctions were lost on the civil rights movement’s right-wing opponents. By painting civil rights activists as communists, or at the minimum dupes of an international communist conspiracy, segregationist southerners were making a bid for the support of conservative anticommunists elsewhere in the country.

They got it. Barry Goldwater, whose anti-liberal and anticommunist political bona fides were so secure he could get away with criticizing the John Birch Society without losing the support of its members, voted against the Civil Rights Act in 1964. The vast majority of conservative publications opposed the bill’s passage, on the grounds both that it was an unacceptable expansion of federal power and that the “mobocratic” and “unruly” civil rights agitators were in effect advocating for socialism. George Wallace, the hyper-segregationist governor of Alabama, recognized the potency of this conspiratorial rhetoric during his third-party run for president in 1968. Shunned by Buckley and the conservative establishment on the basis of his sympathy for New Deal–style welfare programs, Wallace was embraced by the Birchers because of his unwavering opposition to the “communists,” “radicals,” and “agitators” in the civil rights movement.

The rise in prominence of the religious right in the 1970s and ’80s did little to tamp down paranoid political rhetoric. Evangelicals like Jerry Falwell and Francis Schaeffer—as well as Catholics like Paul Weyrich and Mormons like W. Cleon Skousen—conflated liberalism, socialism, and communism under the broader umbrella of “secularism” and built alliances with one another to combat this scourge. Often, this merely meant consolidating preexisting activism: Falwell had been an outspoken opponent of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, and Skousen was a key propagandist for the John Birch Society in the 1960s and early ’70s before penning in 1981 The 5,000 Year Leap, a book that codified many of the shibboleths of the religious right to the present day. The evangelicals and their allies in other denominations were united in their opposition to abortion, gay rights, and feminism—the tangible realities of the nefarious left-liberal agenda.

Anti-Clinton paranoia may have been a necessity for Republicans who yearned to regain power in the 1990s. With relatively little substantive disagreement on policy, the easiest way to maintain energetic opposition was to construct a narrative of criminality and anti-American perfidy that must be countered at all costs.

Increasingly, the communist fingerprints to be found on these cultural changes were not to be found in an overarching conspiracy directed from Moscow—after all, the sexual politics of radical American feminists were hardly those of Leonid Brezhnev—but from a more nebulous grouping of student radicals, intellectuals, and activists. Although the term “cultural Marxism” would not be used to describe this new, somewhat murkier conspiracy until the 2000s, the outlines of the charge were already evident by the late 1970s. In 1980, televangelist James Robison declared in a speech that he was “sick and tired of hearing about all of the radicals, and the perverts, and the liberals, and the leftists, and the communists coming out of the closet,” and called for “God’s people” to fight back.

The collapse of the Soviet Union accelerated these trends. It was no longer possible to accuse liberals and remnants of the left of being in Moscow’s pocket, but this did not stop conservatives from invoking the specter of left-wing radicalism to rally support and justify extremism. It just took more creativity. Pat Buchanan deftly shifted midsentence in his infamous 1992 speech at the Republican National Convention from the Cold War to the “cultural war,” the “religious war . . . for the soul of America,” suggesting that the fight against liberalism, feminism, and the “gay agenda” was not just the equivalent, but in fact the continuation, of the Cold War itself.

The “culture war” was the basis of the Clinton hatred phenomenon in the 1990s, which—as in 2016—was particularly focused on Hillary Clinton. She was the worst of all possible worlds: an elitist big-government liberal with degrees from Wellesley and Yale Law, a feminist who initially refused to change her name after marrying Bill, declined to embrace the image of a mother and housewife in the White House, and was rumored to be the real powerhouse next to her husband.

Bill Clinton had run in 1992 as a “different kind of Democrat,” and after losing Congress in 1994 tacked even more to the right. Clinton embraced financial deregulation, effectively abolished the existing welfare program, and even signaled his openness to partially privatizing Social Security and Medicare. Yet Clinton’s policy concessions to conservatives won him little goodwill from across the aisle. Congressional Republicans embraced scorched-earth legislative tactics under firebrand House Speaker Newt Gingrich, including the 1995 government shutdown, a preview of the right’s nihilistic resistance to Barack Obama over a decade later.Gingrich was a veteran partisan bruiser—as House minority whip he led the successful effort to oust Texas Democrat Jim Wright as speaker for minor ethics infractions in 1989, suggesting for good measure that Wright and other Democrats harbored socialist sympathies given their willingness to negotiate with the Sandinista government to end the Nicaraguan civil war.

But in another sense, the fervid anti-Clinton paranoia may have been a psychic and political necessity for Republicans who yearned to regain power. With Clinton offering real policy conciliations to conservatives, the easiest way to maintain energetic opposition was to construct a narrative of criminality and anti-American perfidy that must be countered at all costs. Right-wing attacks against the Clintons could and did backfire—the president’s approval ratings actually rose during his impeachment—and accusations against Bill Clinton for affairs, sexual harassment, and even rape were easier to dismiss as part of a “vast right-wing conspiracy,” as Hillary Clinton put it, when right-wing magazines were also accusing her of murder. Bill Clinton weathered the Monica Lewinsky scandal, but Clinton hatred never went away. It reappeared with a vengeance in 2016.

The bitter partisan battles of the 1990s intensified trends that had existed on the political right since World War II. Indeed, the creation of Fox News in 1996 was a supercharged throwback to the days of Human Events and the American Mercury. Fox News was necessary, the argument went, because conservative journalists and conservative perspectives were shut out of mainstream broadcasters. Never mind that even Bill O’Reilly had enjoyed a career at CBS and ABC before joining Fox News in its debut year. But while conservative media in the 1950s and ’60s either had a limited reach—the National Review in 1960 had less than a tenth as many subscribers as Time—or were counterbalanced by the FCC’s fairness doctrine, which was on the books between 1949 and 1987, Fox News presented an unchallenged right-wing worldview to millions of viewers twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year.

Conservative pundits repackaged Cold War–era attacks equating liberals with communists during the Bush years. In 2003, Ann Coulter, a frequent Fox News talking head, published Treason: Liberal Treachery from the Cold War to the War on Terrorism, which was a full-throated defense of Joseph McCarthy that accused liberals of being, well, traitors who hated America. The book sold 500,000 copies in its first three weeks. Even the racially charged birther myth—that Barack Obama was not a U.S. citizen, and was a covert Muslim, to boot—was a riff on the old John Birch Society charge that liberals, including moderate Republicans like Dwight Eisenhower, were secret members of the international communist conspiracy. The cry that Obama was a Marxist, Maoist, Muslim Kenyan socialist was almost interchangeable with right-wing attacks directed against the civil rights movement in the 1960s. And the idea that a vast left-liberal conspiracy was both undermining the country and using dirty, underhanded tactics to do so rhetorically justified an anything-goes strategy on the part of the right. Shutting down government. Refusing confirmation votes. Supporting Donald Trump for president.

So-called Never Trump conservatives lament that the Republican Party and, indeed, the conservative movement have ceased to be about ideas beyond slavish devotion to Trump’s cult of personality. But this critique ignores the centrality of the idea of liberal nefariousness even in the self-consciously intellectual corners of the conservative movement. Jonah Goldberg, who has been affiliated with National Review for twenty years, has called for a revived conservative intellectual vigor to tackle the policy challenges of the twenty-first century. He was also the author, in 2008, of the book Liberal Fascism, which—until a last-minute change by Goldberg—bore the subtitle The Totalitarian Temptation from Mussolini to Hillary Clinton.

Even the theory-heavy Chicago School movement that undergirded the post-Reagan shift to laissez-faire economic policy derived its momentum from the perceived need to rescue the “free enterprise system” from the clutches of liberalism, which would otherwise inevitably lead to communism. Robert Bork, the academic, judge, and Nixon administration official who was perhaps the preeminent ideological conduit between academia and government—and whose 1996 book Slouching Towards Gomorrah: Modern Liberalism and American Decline is exactly what it sounds like—described his antitrust theories as an antidote to the “reckless and primitive egalitarianism” of the Warren Court.

Trump is, in many ways, the ultimate embodiment of this long-standing tendency on the right. His transformation from New York Democrat to Republican Party celebrity began by embracing the birther conspiracy; he even took credit for Obama’s eventual decision to release his long-form birth certificate. As president, he has wondered aloud why Attorney General Jeff Sessions hasn’t personally defended him from the Russia investigation in the same way that, in Trump’s Fox News–fueled fantasies, Eric Holder once shielded Obama from “scandals” like “Fast and Furious.”

The idea that the left is depraved, corrupt, and ruthless has been an important strain of American conservatism since the movement began. But in the Trump era, it has metastasized. Right-wing policy ideas have been so thoroughly discredited—does anyone even argue anymore that trickle-down economics will ensure mass prosperity?—that the only apparent reason for conservatism’s existence is to fight back against evil liberals. This is, of course, not the sign of a healthy political movement. The right’s support for McCarthy has been a long-standing embarrassment for American conservatism. Its embrace of Trump may be history repeating itself.