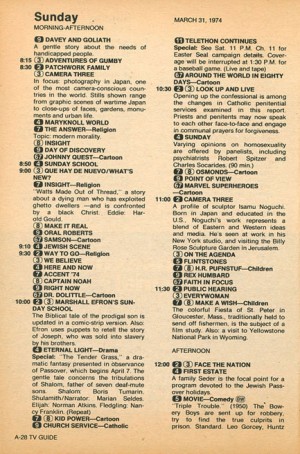

In the spring of 1978, the program guide published by a Los Angeles public television station contained more than just schedules; it told viewers when they could watch its programs—and what they were allowed to do with those programs.

Some programs, the guide showed, could be taped without restriction. For others, viewers could record as long as they followed certain restrictions, such as deleting the recording within seven days. Still other programs shouldn't be recorded at all, since the copyright holders objected to such recording.

In all, out of the 107 television programs that would be broadcast on Channel 58 that season, 62 of them authorized some home taping. Only 21 of them—about 20 percent—allowed "unrestricted" home taping.“Everyone said the sky is falling. Broadcasters were saying no one would ever advertise if people time-shift.”

Videotape recording machines belonged to a relatively small number of households back then, and it's unlikely that many of the owners paid close attention to such complex rules about what they could tape and how long they could keep it. The Channel 58 guide was reflective of the limbo-state in which home recording machines found themselves, however. After being on the market two years by that point, it still wasn't clear whether video tape recorders (or VTRs, as they were then called) were actually legal. Indeed, movie studios argued that they were not.

In 1976, shortly after its Betamax machine hit the market, Sony Corporation had been sued by the studios, which said that home taping was illegal. They hoped to force Sony to pay a royalty for each device and cassette sold or to withdraw from the market. Sony fought back, saying that many forms of home recording were absolutely legal and that, in any event, it couldn't be held responsible for what its customers did with its machines.

"Everyone said the sky is falling," said Gary Shapiro, head of the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA), in an interview with Ars about the Betamax decision. In the early 1980s, Shapiro worked for the CEA's predecessor organization and was at the heart of an all-out lobbying war in the halls of Congress. "Broadcasters were saying no one would ever advertise if people time-shift."

The Sony Corp. v. Universal Studios ruling "was a statement that to allow innovation to flourish, government can't protect business models," said Shapiro. "Betamax is the 'Magna Carta' of the innovation world."

But another world was possible—in fact, it was just one vote away. In 1981, the US Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit handed down a decision that would have devastated Sony; when the Supreme Court overturned that ruling three years later, it did so on a 5-4 vote.

Today, on its 30 year anniversary, the ruling is more relevant than ever before.

From Megaupload to 3D printing, consumer-accessible tools for electronic copying remain at the center of the biggest legal fights in technology—and the Sony Betamax decision remains a key touchstone. Later this year, the Supreme Court will hear a case regarding Aereo, a company that has captured TV broadcasts and repackaged them for the Internet. Even though few consumers today rely on over-the-air broadcasts, whether or not there's a fair use right to record them in this way is up in the air yet again.

“How many people needed to do that?”

The first video recording device was demonstrated in Bing Crosby's studio in California back in 1951. It was essentially a beefed-up audio recorder, and it had some serious limitations. It held 16 minutes of material on a reel and suffered from "poor resolution, flicker, diagonal disturbances, and occasional ghosts," according to James Lardner's account of the Betamax saga, Fast Forward: Hollywood, the Japanese, and the VCR Wars.

The device got the industry's attention, however, even though home recording was unimaginable at that time. RCA jumped into development, but its engineering efforts mostly led to bigger and faster-spinning tape reels. Tiny Ampex Corporation in Redwood City, California used "transverse recording" and dropped a fixed-head system for one where tape was recorded with moving heads. Ampex's breakthroughs led to a machine that held 90 minutes of programming on a 14.5-inch reel.

Unveiled to radio and TV broadcasters at a 1956 convention, the Ampex machine was an obvious triumph. The company knew there was a market in the media industry, but consumer potential for the unwieldy and expensive machine was expected to be zero. Ampex set the lofty goal of selling 30 machines in four years.

"It was just going to be used for time delay, and how many people needed to do that?" one Ampex engineer told Lardner.

By 1960, Ampex wanted to use "helical scanning" to make smaller machines. It hired Sony, which had made a name for itself in small radios, to make transistorized circuits for the new machines. As part of the compensation, Ampex gave Sony rights to sell video tape recorders in the non-broadcast market.

For several years, it looked like Ampex had given Sony the rights to a market that didn't and wouldn't exist. Sony first pushed a consumer-oriented VTR in 1961, but for many years it had almost nothing to show for its efforts. In 1965, the peak of Sony technology was the CV-2000, pumped up as the first "home videocorder." A 7-inch reel of tape could hold a half-hour of programming. The machine came with a built-in TV, cost $1,000, and weighed 66 pounds. It used "skip-field recording" that didn't grab every image and had a hazy picture. Worse, it was black-and-white in a country that was just falling in love with color television.

The machine wasn't widely adopted, but it had respectable sales to schools and other institutional buyers. Ampex didn't like the success. Its deal with Sony was cancelled in 1966, and Ampex demanded an eight percent royalty on future sales. A patent infringement lawsuit followed, which was settled two years later.

Sony was then on its own and increasingly focused on the home. In 1971, it produced another iteration of home recorder: the U-matic. The machine used a book-sized cassette and provided color recording; Sony believed that it was finally ready for the US and Japanese consumer markets.

Consumer reaction was lukewarm, however. The cheapest versions of the U-matic still cost over $1,000, and half-hour cassettes were $30 each. U-matics were compact, though, and made inroads among broadcasters; CBS used one to cover President Richard Nixon's 1974 trip to Moscow.

reader comments

93