Collectibles Club — a membership association for sports memorabilia fans and other hobbyists — sounded innocuous enough when it was launched in 2013.

But as law enforcement agencies subsequently discovered, the company was actually a front for Coin.mx, a bitcoin exchange responsible for laundering more than $10 million over the span of two years.

The plot involved some twists fit for Hollywood — investigators found that those behind the scheme went so far as to bribe the head of a New Jersey credit union so they could take control of the institution and further evade the government’s scrutiny.

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or Fincen, a bureau of the Treasury Department, recently held up the case as a triumph for the Bank Secrecy Act — and the work banks undertake to help stop money laundering — as part of an annual awards program. Fincen noted in a May press release that “a high volume of sensitive financial information was instrumental” in shutting down the operation.

The story is a positive one — financial data also helped prosecutors find out that the exchange was connected to a hacker involved in several high-profile data breaches, including one at JPMorgan Chase. Investigators found that the exchange was used to launder money for the criminal organization behind the cyberattacks, which stole the personal information of more than 100 million people.

Still, there’s a problem. The aggregate data tells a far more sobering story.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that as much as $2 trillion is illegally laundered around the world each year — while law enforcement reportedly catches less than 1% of that.

As much as $300 billion in illicit funds make their way through the U.S. financial system in a given year, according to the Treasury Department.

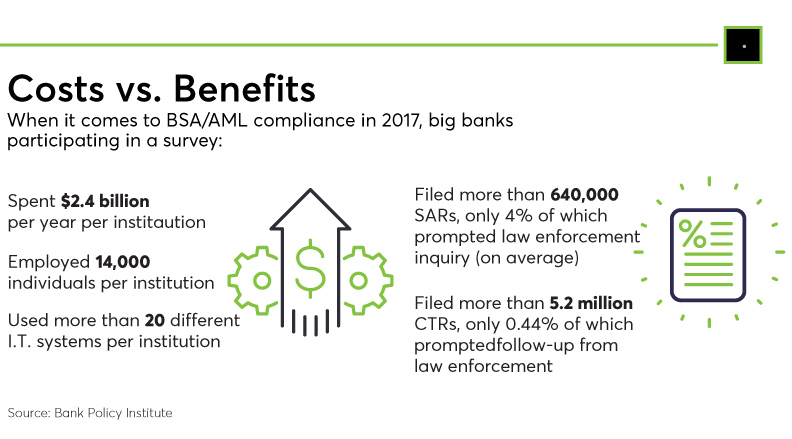

All the while, banks are submitting millions of BSA reports annually, running up a sectorwide compliance bill of $25 billion, money spent on a system in which, according to the banking industry, the vast majority of filings go unseen, much less are used in criminal prosecutions.

It’s a multitrillion-dollar problem that has plagued the financial industry and government officials for decades: Can we make the system less burdensome on banks, while also providing law enforcement with the information on criminals that it actually wants?

It’s not that the current system isn’t helping the cops on the beat do their jobs or that the data being compiled is worthless. But there are critical disconnects waiting to be addressed, and incentives across the regime that remain at cross-purposes. The question is whether there’s now finally enough collective interest to see concrete improvements put into place — even as significant details still need to be ironed out.

“Everybody in the regime wants to try to make it more efficient and effective, but everybody’s got a different definition of efficient and effective,” said Jim Richards, the former global head of financial crimes risk management for Wells Fargo and the founder of RegTech Consulting.

‘Mountains’ of data

For bankers, the sheer volume of information that must be filed under current standards can be overwhelming to comprehend — more than 15 million reports per year on cash transactions over $10,000 and suspicious activities.

“All of these reports are like hay straws — they’re just piling up, and there may or may not be a needle in there somewhere,” said Camden Fine, president and CEO of Calvert Advisors and the former head of the Independent Community Bankers of America. “But we can’t find the needle because we’ve created mountains, literally, warehouses full of mainly innocuous transactions.”

A Bank Policy Institute survey last year of 19 major banks found that they produced 640,000 suspicious activity reports and 5.2 million currency transaction reports in 2017, based on 16 million alerts. But law enforcement agencies followed up on only 4% of the SARs and less than 0.5% of the CTRs.

This state of affairs is largely a product of how the regime has been expanded over time. The system was built in 1970 to catch mob bosses and tax cheats, but was amended in the 1980s to add a focus on drug cartels. After 9/11, the regime was modified again to address terrorist financing. And a growing number of organizations, from money transmitters to casinos to jewelers, now have anti-money-laundering responsibilities as part of running their businesses.

"You have a system that has multiple objectives — that defaults into producing as much information as possible and leaving it to someone else to figure out what’s useful,” said Aaron Klein, policy director of the Brookings Institution’s Center on Regulation and Markets.

While bankers see this mountain of data as a drawback, law enforcement officials often do not. Indeed, one of the fundamental tensions in the debate between the financial industry and law enforcement is that from the latter’s point of view, the more data, the better. Officials argue that just looking at the number of SARs used to put specific bad actors in jail misses the point.

“When I looked at SARs, I looked at the full universe of SARs from a macro level, and we were analyzing SARs not only to identify SARs for ongoing investigations or predicate investigations, but for me, more importantly, I was trying to identify emerging trends — SARs are a huge part of those types of analytics, especially in terrorism,” said Dennis Lormel, a former chief of the FBI’s financial crimes section who is now the president and chief executive of DML Associates, a consultancy.

Fincen reports that users of its database have initiated more than 10 million queries over the five past years, and that more than 21% of FBI investigations draw on Bank Secrecy Act data.

As technology has advanced, this evolution toward using the data for trend-spotting has accelerated, opening up new avenues for government officials to develop insights beyond the specifics contained in any one report. Still, those in the financial industry say this means there’s arguably even less reason for law enforcement to seek changes to make the system more efficient, particularly if the result is that less data comes over the transom.

Banks point in particular to cases where institutions feel compelled to file reports simply to avoid potential pushback from regulators — so-called defensive suspicious activity reports. Law enforcement isn’t necessarily very worried about such filings, bankers say, but they come at a price.

“What’s changed is, the cost of all the defensive and useless SAR filings is not that you’re wasting the time of a law enforcement officer who has to read it; it’s the opportunity cost for the bank,” said Greg Baer, chief executive of the Bank Policy Institute. “It’s having to do investigations in order to make that SAR decision that take resources away from actual innovation and creative thinking about how the bad guys behave.”

John Ciulla, the president and CEO at the $27.6 billion-asset Webster Financial in Waterbury, Conn., is almost wistful at the idea of reform.

“Imagine if you could pull all your resources and have the best technology and have all your transactions monitored,” he said in an interview earlier this year. Anti-money-laundering compliance “is a costly endeavor. If you’re a small bank, you don’t get a discount to put in the technology and have the people to chase down a lot of false positives. So if there’s a way to simplify, increase the [dollar] amount of transactions we are looking at and potentially merge technology across a group of banks, that would be terrific.”

Siloed regime

There are a growing number of efforts aimed at improving the system — including those to enhance the quality of information that gets passed on to the FBI and other officials and to reduce the compliance burdens associated with those reports.

On the front end of the detection process, many observers are watching eagerly to see if beneficial ownership legislation — aimed at eliminating the use of anonymous shell companies — can make it over the finish line this term. There are bills pending in the House and the Senate that would require the true owners of a corporation to register with the government when a firm is formed, instead of through the banking system, in cases where those companies seek a bank account.

“Beneficial ownership transparency is the foundational reform — without that the system can’t really improve,” said Clark Gascoigne, deputy director of the Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition.

At the same time, the industry has been pushing for more feedback and transparency around how the information being collected is used — to help better inform which types of reports are most valuable and how they aid the intelligence communities. Many have pointed to the transformative role that artificial intelligence and machine learning could one day play, simplifying and improving the process for financial institutions — although widespread adoption of such technologies is likely still years away, as the technologies will need to be tested for their effectiveness against traditional compliance.

“People in different agencies and institutions put different value on different pieces of information,” said Kenneth Blanco, the director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. (Photo: Bloomberg News)

“People in different agencies and institutions put different value on different pieces of information,” said Kenneth Blanco, the director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. (Photo: Bloomberg News)

“The tools we have were written in an era when all these processes were originally designed on paper — and now they can be digitized. We can turn the information in the system into digital forms that we can work with much more data, and we can bring machine learning and artificial intelligence into analyzing the data,” said Jo Ann Barefoot, co-founder of the regtech startup Hummingbird and a former deputy comptroller of the currency. “And the secret to it is to enable computers to find the big patterns of crime that we can’t detect just by looking at spreadsheets or reading suspicious activity report.”

Baer said that the use of such technologies will be integral to improving and simplifying the system.

“The real holy grail is on the monitoring side. Banks of every size are still using off-the-shelf software to do transaction monitoring, which incidentally, sophisticated criminals have that software too and know how to avoid it,” he said. “You can get to a world where you are generating dramatically fewer alerts, filing significantly fewer SARS and yet are catching exponentially more bad guys."

Until recently, regulators appeared wary of AI programs. Even if supervisors allowed banks to test them, there was a concern that examiners might still want them following the same rules-based system they’ve used in the past. In other words, banks were allowed to pursue AI, but didn’t really any see benefits from doing so, because they feared having to keep using the traditional methods to detect suspicious activity as well.

Critically, there are signs that view is changing. Fincen and the prudential regulators issued a joint statement last year encouraging banks to consider the use of new technologies to comply with AML standards — something Baer called “a good sign.” That’s in addition to a second joint statement that highlighted the potential benefits that community banks and credit unions could gain by pooling BSA resources through collaborative agreements. In July the group issued a third joint statement, this time emphasizing the use of risk-based exams for AML compliance. Fincen also announced a new “innovation hours” program in May, which will give financial institutions and startups the opportunity to hold demonstrations of new AML technologies at the bureau.

“We are much more coordinated than I think we have been” with the prudential regulators, said Kenneth Blanco, Fincen’s director, noting that he regularly meets with the heads of the agencies. “We have monthly meetings to talk not only about innovation, but about things that are happening out there in the financial sector, how we can work together, how we can be more efficient.”

Blanco said he has invited bank CEOs to meet with him privately to discuss their concerns about the system. “I will walk them through exactly what it is we’re using their information for, so that they can understand that the information — and the money that they’re spending — is valued,” he said.

Fincen has similarly indicated that it’s working with a private vendor on a process aimed at determining what’s working and what isn’t under the current regime.

“If you think about it on its face, what is the value of BSA? It sounds like a pretty simple question, but it really is hard — people in different agencies and institutions put different value on different pieces of information,” Blanco said.

But bankers don't necessarily feel like Fincen is working with them.

"If you go up to the Hill and talk to the legislators, they hear from Fincen and they want to keep things the way they are," said Jim Reuter, the president and CEO at the $18.5 billion-asset FirstBank Holding Co. in Lakewood, Colo. "The problem is that we are still operating as if it was 25-30 years ago. I feel like if we worked together, banking and Fincen, we could just be much more strategic."

At the same time, broad AML legislation recently introduced by a bipartisan group of senators — Mark Warner, D-Va., Doug Jones, D-Ala., Tom Cotton, R-Ark., and Mike Rounds, R-S.D. — would require the Department of Justice to report annually on how frequently law enforcement agencies use Bank Secrecy Act reporting as part of their investigations. The bill would also establish beneficial ownership reporting requirements and mandate a number of steps aimed at improving coordination between all of the different players in the regime.

Draft legislation being debated in the House would similarly establish a voluntary “Fincen Exchange” between financial institutions and their affiliates, law enforcement and Fincen, designed to improve the efficacy of the system.

All of these efforts go to vital questions banking officials and others have been asking themselves for more than two decades: What is useful information, how is it being used and where do we go from here?

“What the CFOs and the CEOs are saying is, what are we getting for all this money we’re pumping into the AML/BSA regime?” said Richards, the former Wells Fargo executive. “Can we produce fewer alerts and have it cost less and investigate fewer cases and file better SARs? The answer to that is maybe — but we don’t know what a better SAR is.”

Still, AML reform has been on the minds of many for years, with the need for updates and improvements fairly clear to most parties — somewhat of a rarity in policymaking circles. But that’s not to say those good intentions are always enough to lead to concrete changes, particularly when it comes to the more sweeping reforms being debated in the divided Congress.

For example, while the House’s beneficial ownership bill enjoys bipartisan support and recently advanced out of committee, it has been opposed by the Chamber of Commerce and other powerful business interests, raising questions about its fate on the House floor and in the Republican-led Senate. At the same time, smaller institutions have pushed for raising the thresholds for suspicious activity reports and currency transaction reports as a way to reduce reporting burdens, even as other industry officials argue that doing so would open up dangerous loopholes in the system.

“In some ways, it’s classic Washington — there’s a sense that something should be done, but not necessarily an agreement on what that should be,” said Edward Mills, a policy analyst at Raymond James.

That’s particularly true as large institutions, most recently Deutsche Bank, continue to stumble amid headline-grabbing compliance failures.

Regulatory oversight

And yet compliance with anti-money-laundering rules is very much on the minds of banking officials as part of the reform effort. Industry experts argue that bank examiners don’t have enough insight into the work institutions do to report suspicious activity, distorting how their compliance programs are evaluated.

“The examiners who determine compliance are not allowed to know, in all but rare cases, what becomes of the suspicious activity reports that are filed,” Baer of the Bank Policy Institute said. “So that compliance rating is driven far more by things like, are there written policies and procedures, has there been strict one hundred percent adherence to those policies and procedures, rather than the efficacy of the SARs that are filed.”

"What that leads to is, AML is examined much the same way as any other function — through a check-box kind of approach,” Baer said.

This in turns shifts the balance with regard to bank priorities, with compliance becoming the main focus. That includes an over reliance on defensive SARs and a fixation on minutiae, according to industry experts.

“We have these laws for one reason and one reason alone — and that’s to get valuable data and information in the hands of law enforcement, so there can be a reaction,” said John Byrne, an expert on anti-money-laundering issues and vice chairman of AML RightSource. “When regulators are criticizing banks for being a couple of days late in a filing or putting a company on a cash reporting exemption list by error, that’s a problem.”

For their part, regulators are taking steps that they say are designed to meet some of these concerns — including through the regular meetings held by the heads of Fincen and the prudential agencies, along with even more frequent discussions among staff.

“There is significant collaboration across all parts of this — among the regulators, among Congress, among all stakeholders,” said Grovetta Gardineer, the senior deputy comptroller for bank supervision policy at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. “There continues to be a heightened focus in order to really ensure that we can protect the system — and that’s a good thing that so many eyes are on it."

That collective effort also includes meetings held through the Bank Secrecy Act Advisory Group, which is made up of government officials, law enforcement bodies, financial institutions, trade groups and tech startups, officials said.

“We’ve re-energized the BSAAG since I’ve been here — we’re now making it an even bigger event, and our subgroups and our workstreams are more focused,” said Blanco, the Fincen director, who joined the bureau in late 2017.

Still, the biggest unanswered question looms large: How much change will the system undergo in coming years and will it be enough? To the degree there are broad strokes of agreement across the industry and government and other players, there are numerous areas where the essential details still need to be hashed out. Absent that, progress is likely to remain more piecemeal than comprehensive. What remains to be seen is whether that’s sufficient to keep up with the savviest criminal minds out there.

The bad actors “are getting smarter,” Gardineer said. “They’re figuring out how to get around some of these systems — and so, we have to keep pace in order to protect the integrity and the safety of the financial system.”