Trust Is Collapsing in America

When truth itself feels uncertain, how can a democracy be sustained?

“In God We Trust,” goes the motto of the United States. In God, and apparently little else.

Only a third of Americans now trust their government “to do what is right”—a decline of 14 percentage points from last year, according to a new report by the communications marketing firm Edelman. Forty-two percent trust the media, relative to 47 percent a year ago. Trust in business and non-governmental organizations, while somewhat higher than trust in government and the media, decreased by 10 and nine percentage points, respectively. Edelman, which for 18 years has been asking people around the world about their level of trust in various institutions, has never before recorded such steep drops in trust in the United States.

“This is the first time that a massive drop in trust has not been linked to a pressing economic issue or catastrophe like [Japan’s 2011] Fukushima nuclear disaster,” Richard Edelman, the head of the firm, noted in announcing the findings. “In fact, it’s the ultimate irony that it’s happening at a time of prosperity, with the stock market and employment rates in the U.S. at record highs.”

“The root cause of this fall,” he added—just days after polling revealed that Americans’ definition of “fake news” depends as much on their politics as the accuracy of the news, and a Republican senator condemned the American president’s Stalinesque attacks on the press and “evidence-based truth,” and a leading think tank warned that America was suffering from “truth decay” as a result of political polarization and social media—is a “lack of objective facts and rational discourse.”

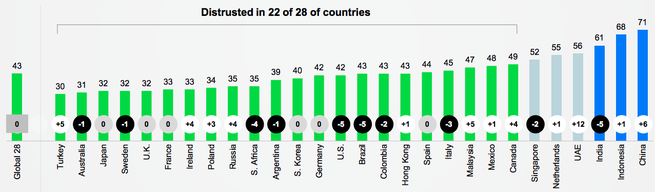

It used to be that what Edelman labels the “informed public”—those aged 25 to 64 who have a college degree, regularly consume news, and are in the top 25 percent of household income for their age group—placed far greater trust in institutions than the U.S. public as a whole. This year, however, the gap all but vanished, with trust in government in particular plummeting 30 percentage points among the informed public. America is now home to the least-trusting informed public of the 28 countries that the firm surveyed, right below South Africa. Distrust is growing most among younger, high-income Americans.

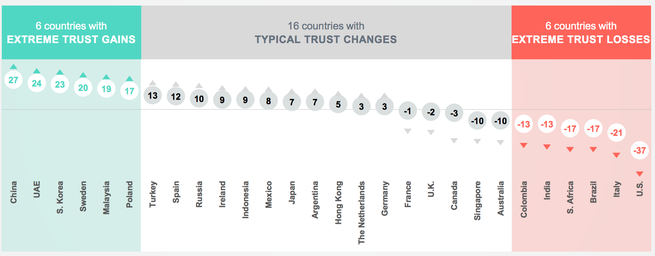

But whereas trust is falling in the United States and a number of other countries with tumultuous politics at the moment, including South Africa, Italy, and Brazil, it’s actually increasing elsewhere, most prominently in China. Eighty-four percent of Chinese respondents said they trusted government—levels the United States hasn’t seen since the early Johnson administration—and 71 percent said they trusted the media. The world’s two most powerful countries, one democratic and the other authoritarian, are moving in opposite directions. In each case, the trajectory is largely being determined by people’s views of government.

Chinese respondents are probably reflecting on the upward mobility and improving quality of life that their political leaders have helped deliver, David Bersoff, the lead researcher for the Edelman report, told me: “I’m looking at my life now and it looks a lot better than it did before, and I can look forward and still see things that would get even better.” When I asked Richard Edelman why survey participants tended to trust technology companies much more than government, he reasoned that it was because those companies “have products that perform for you every day—whether it’s your cell phone or your airline.” Chinese respondents might have been making a similar statement about the government’s performance.

“There’s a lot of chaos and uncertainty in the world, and when there is chaos and uncertainty in the world centralized, authoritative power tends to do better,” Bersoff added. (It’s worth noting that other countries with high trust levels in the report range politically from democratic India to more-or-less democratic Indonesia and Singapore to the undemocratic United Arab Emirates.)

Why, though, is trust eroding in the United States in the absence of an economic crisis or other kind of catastrophe? What’s changed, according to the Edelman report, is that it’s gotten much harder to discern what is and isn’t true—where the boundaries are between fact, opinion, and misinformation.

“The lifeblood of democracy is a common understanding of the facts and information that we can then use as a basis for negotiation and for compromise,” said Bersoff. “When that goes away, the whole foundation of democracy gets shaken.”

“This is a global, not an American issue,” Edelman told me. “And it’s undermining confidence in all the other institutions because if you don’t have an agreed set of facts, then it’s really hard to judge whether the prime minister is good or bad, or a company is good or bad.” A recent Pew Research Center poll, in fact, found across dozens of countries that satisfaction with the news media was typically highest in countries where trust in government and positive views of the economy were highest, though it didn’t investigate how these factors were related to one another.

America actually falls in the middle of surveyed countries in terms of trust in the media, which emerges from the Edelman poll as the least-trusted institution globally of the four under consideration. (In the United States, the firm finds, Donald Trump voters are over two times more likely than Hillary Clinton voters to distrust the media.) Nearly 70 percent of respondents globally were concerned about “fake news” being used as a weapon and 63 percent said they weren’t sure how to tell good journalism from rumor or falsehoods. Most respondents agreed that the media was too focused on attracting large audiences, breaking news, and supporting a particular political ideology rather than informing the public with accurate reporting. While trust in journalism actually increased a bit in Edelman’s survey this year, trust in search and social-media platforms dipped.

In last year’s survey, the perspective that many respondents expressed was “‘I’m not sure about the future of my job because of robots or globalization. I’m not sure about my community anymore because there are a lot of new people coming in. I’m not sure about my economic future; in fact, it looks fairly dim because I’m downwardly mobile,’” Edelman said. These sentiments found expression in the success of populist politicians in the United States and Europe, who promised a return to past certainties. Now, this year, truth itself seems more uncertain.

“We’re desperately looking for land,” Edelman observed. “We’re flailing, and people can’t quite get a sense of reality.” It’s no way to live, let alone sustain a democracy.