Today is the last day of the annual Ars Electronica festival, held in Linz Austria. Over the past 37 years it has aimed to provide an environment of “experimentation, evaluation and reinvention” in the area broadly defined as art, technology and society. Its top award, the Golden Nica, honours forward-thinking work with broad cultural impact, in an effort to “spotlight the ideas of tomorrow.” However, the prize, hailed by many in the field as the top honour for artists working with science and technology, has a gender problem.

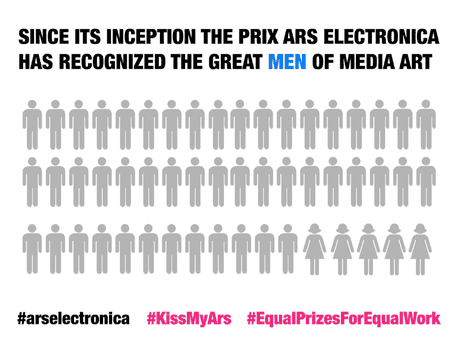

This was uncovered by artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg after she received an honourable mention in the Hybrid Arts Category last year. The prize’s online archive showed that throughout its 29-year history, 9 out of 10 Golden Nica have been awarded to men.

It was only weeks before the festival and her work was already shipped. Unable to withdraw, Heather began discussing the problem with other artists to develop a plan. A painstaking review of the statistics confirmed that more than 90% of winners self-identified as male. Although fewer women had applied, there was no shortage of great female artists among the applicants: the archive included internationally recognized women such as Rebecca Gomperts, Lillian Schwartz, Mariam Ghani, Pinar Yoldas, Daisy Ginsberg, Holly Herndon, Kaho Abe, and Ai Hasegawa. In response, Heather and the other artists developed a social media campaign: #KissMyArs.

The campaign spread quickly, generating a host of strong responses. While many were supportive, some voiced disagreement, including 2013 Golden Nica winner Memo Atken. He commented on what he viewed as the campaigners’ misrepresentation of statistics, focusing only on the winners rather than diversity of submissions. After being confronted with a significant backlash to these comments on social media, pointing out among other things that the prize was not a lottery and there was no shortage of impressive female applicants, Atken apologised.

On the flip side artists Golan Levin and Mushon Zer-Aviv critiqued the campaign as not being radical enough for their liking and calling for a “feminist revolution across media arts.”

Women’s experiences in art and technology

In an insular field like art and technology, making a statement means that you risk your career. Heather Dewey-Hagborg writes, “My participation in this campaign stemmed from a frustration that this highly esteemed prize was one designed for men, and others need not apply. As women in art and tech we are consistently under-recognised, under-funded, and written out of history. We are made to feel that our work must simply not be as good as that of our male peers, and if only we made better work we would attain the same accolades and accomplishments as they did. Last year I finally realised that this was bullshit.”

Addie Wagenknecht, a collaborator on the campaign, became aware of issues of gender bias in the tech industry when she joined a game development company out of college. Constantly surrounded by “a few thousand men” at game conferences started to feel suffocating, although a decade later she felt a shift in attitudes, not only toward women but also people of colour and from LGBTQ communities.

Nevertheless, Addie sees Ars Electronica’s top prize, as “the perfect metaphor of how women are represented”. It is a golden sculpture of an idealised female form, with her head cut off: “I find the irony in the ‘award’ being of a headless woman, to speak volumes towards how we commodify women within the communities in which we claim to be honouring.” She sees the male-bias of the prize as connected to a larger systemic problem which excludes women from exhibitions, under-cuts and discounts women’s work in galleries, and ultimately cuts women out of the larger canon of contemporary art.

Heather echoes Addie’s experiences. She remembers “with horrific clarity when I became aware of myself as a ‘woman in tech.’” Her college experience had been mostly female, and she was surprised by the change in tone in her first male-dominated work environment when she took a job as a software developer. At an after-work drinks event she casually found out that she was making substantially less money than her male colleagues, most of whom had less experience: “All at once in a single moment I became conscious of myself ... as a woman whose skills and experience and creativity were devalued. As a woman out of place.”

Suggestions for positive change

Change is possible. At Eyebeam, a prestigious art and technology centre in New York, the application process was recently revised to make it more accessible to underrepresented groups. This resulted in what they termed “the very first year”, the first time the number of women awarded residencies and fellowships outnumbered men. Eyebeam director Roddy Schrock explained that “we’ve institutionally raised the flag” on the issue of diversity.

Realizing that women often devalue their own expertise and qualifications, that they tend to demure their skills in applications, and to have less visibility than male peers, Eyebeam developed a list of strategies for becoming more inclusive:

- Reach out to women with personal invitations to encourage applications.

- Change the application language to focus on process rather than product.

- Place more emphasis on the interview than the written application.

- Do independent research about the applicants.

- Once women are accepted, make a point to highlight their work to the media.

These are tactics that could be deployed at almost any institution in any field. But since we know that both STEM careers and elite arts can be inhospitable to women it is imperative that action is taken within art and technology. Yet to date Ars Electronica has not commented publicly on matters of inclusivity, nor have they taken strong measures to improve on their track record.

Institutions like Ars Electronica have a tremendous opportunityto set a global example by highlighting diverse voices which run counter to the mainstream, and to open public dialogue around the problems, benefits, and tradeoffs new technology is bringing. If there is an “ask” associated with the #KissMyArs campaign it is for marginalised artists to be given a seat at the table; to have a voice in helping reshape this competition into one that is at once more inclusive and more relevant.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg, artist and bio-hacker

Addie Wagenknecht, artist and founder of Deep Lab

Camilla Mørk Røstvik, art and science historian and postdoctoral researcher

Kathy High, artist, curator and scholar

Update [21.09.16]: Eyebeam have asked us to clarify that, since the discussions

reflected in the comments above, their review policy has evolved

further. They suggest that the most effective strategy so far has been

simply composing a jury that is inclusive, and not only in terms of

gender.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion