Social media’s recent embrace of #BlackLivesMatter was a long time coming

The groundwork has been laid for years.

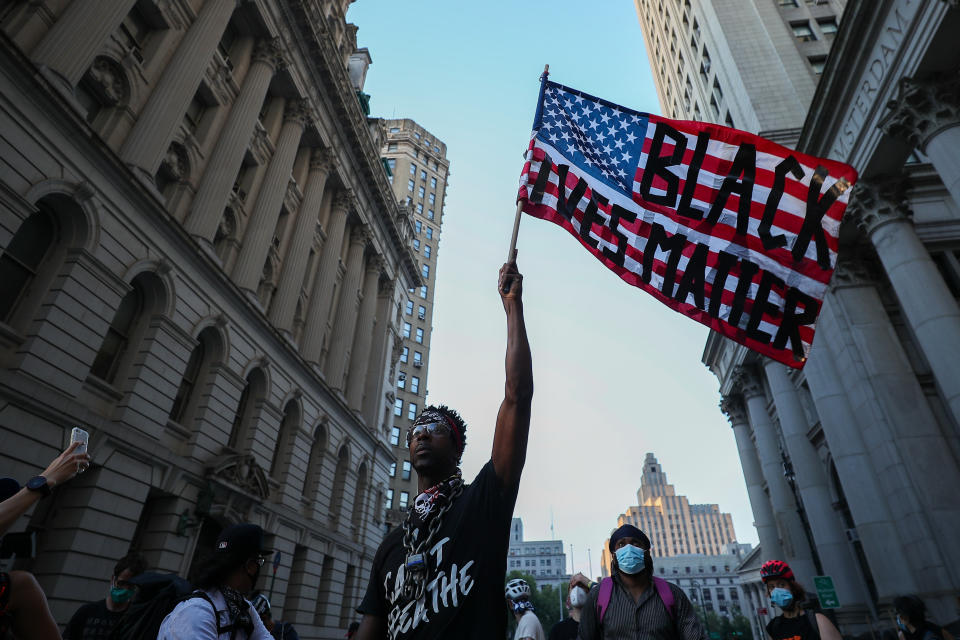

Since the murder of George Floyd on May 25th, the country has seemingly undergone a collective awakening. Not only have protests erupted across the US, but social media has become a hotbed for activism and education on systemic racism. It’s not unusual to see posts on Twitter and Instagram that share everything from the history of Juneteenth to a list of anti-racist books one should read. The latter has become so popular, in fact, that on June 5th, five of the top 15 titles in the New York Times list of best-selling nonfiction books address racism. At a time of this writing, there are 12.

But while this all seems to have exploded in just the past few weeks, the truth is, the rise of Black Lives Matters activism on social media has a long history. It started back in 2013, when Alicia Garza, a labor organizer, used the phrase in a Facebook post after George Zimmerman was acquitted for shooting and killing Trayvon Martin. Patrisse Cullors, another community organizer, added a hashtag to it. A fellow organizer, Opal Tometi, bought the domain name. In an interview with The New Yorker, Tometi said that was the start of the movement:

“And we start to use this hashtag as our umbrella language, and we share it with other community organizers in our network. And then 2014 happened, when Michael Brown was murdered. We are reeling and shocked and seeing how different people in Ferguson are met with a militarized police force, and that gets us going again and we do a Black Lives Matter Freedom Ride. So hundreds of us are on the ground and from that point we develop a network, because people are like, Hey, Fergusons are everywhere, and we don’t want to just go back home and act like this was a one-off act of solidarity. We want to do something. And that was essentially the beginning of our network.”

The hashtag is, therefore, mostly used as a slogan, and as a way to spread awareness of the movement. “While some people may think that the hashtag comes first, most research shows that organizing and on-the-ground activism is what galvanizes the movement,” said Allissa Richardson, a professor at the University of Southern California who recently authored Bearing Witness While Black, a book about social media use in Black Lives Matter activism. “Think of the civil rights movement, for example, who had activists who were saying ‘We shall overcome.’ That would have been their slogan, their hashtag.”

Richardson said that in some ways, the entire #BlackLivesMatter movement sits on top of the shoulders of the Black online activists that came before. “It should be clear that Black people have always been early adopters of the Internet,” she said, adding that one of the earliest social networks was Black Planet. It was founded in 2001, and would eventually form the basis of MySpace’s architecture. “Web 2.0 began with Black people, it began with Black engineers, and Black bloggers who were telling stories. You would hear murmurings of outrage for Sean Bell, who was shot the day before his wedding, and the protests for Amadou Diallo’s death. As we begin to laud Facebook and Twitter for being a platform of openness, we have to credit the Black predecessors who paved the way.”

In 2014, the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag grew to national prominence. According to the Pew Research Center, the hashtag was used 1.7 million times on Twitter in the span of three weeks after a Ferguson grand jury decided not to indict police officer Darren Wilson, who shot and killed Brown. Since then, the hashtag would spike in use several more times, such as when Alton Sterling was shot by police officers in Louisiana on July 5th 2016, and when Philando Castile was killed in St. Paul, Minnesota the very next day.

But as the hashtag grew in popularity in 2016, there were questions as to whether it was really useful. “A lot of people asked me, ‘What’s the magnitude of the Black Lives Matter hashtag? Were laws changed?’” said Charlton McIlwain, a media professor at New York University who co-authored a report for the Center for Media and Social Impact entitled “Beyond the Hashtag: #Ferguson, #Blacklivesmatter, and the online struggle for offline justice.”

“And I had to say, well, no,” McIlwain continued. “But that’s not the domain where we should access it. It’s a media campaign, in a sense. And the barometer was really about the movement being able to garner sustained attention to issues of racial justice over a long period of time.” In short, to him, the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag movement was more about raising awareness about police brutality than, say, actually changing public policy.

That’s partly why he said the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag didn’t really get much traction between 2016 and 2020. “The social media space was not the only battleground, nor was it the most important one,” said McIlwain. “The leaders of the movement began to say, you know, our real battle is in the courthouse, the state house, the local legislatures and so forth. And that work is, you know, invisible. It’s not sexy or as attention-grabbing as viral memes.” Plus, McIlwain said that social media also became less appealing during that time. “Twitter became very toxic… it seemed to be driven by trolls and all kinds of terrible things. There was a sense that people didn’t want to continue to create a movement on these platforms.”

But, in the last month or so, that seems to have changed abruptly. Following the death of George Floyd, the use of #BlackLivesMatter practically exploded. According to the Pew Research Center, the hashtag has been used around 47.8 million times on Twitter from May 26th to June 7th. On May 28th, the Pew Center said it noted a huge spike of 8.8 million tweets with the hashtag, which is the highest number of uses of the hashtag in a single day.

What’s especially surprising this time around, is that the activism hasn’t just resided online. From in-person protests to real-life debates in Congress, the Black Lives Matter movement has transcended the hashtag. “It’s had very real, tangible outcomes,” said McIlwain. He cited police departments making dramatic changes and policy shifts, and companies changing their hiring practices. “The outpouring of all of this all at once, is at a magnitude that I have not ever seen, particularly as it pertains to racial justice.”

According to McIlwain, none of the online activism we’ve seen in the past few weeks would’ve happened without the extensive groundwork laid by #BlackLivesMatter activists since 2013. “As soon as all of this started, there was no mistake,” he said. “Black Lives Matter was back in the headlines in a very real way. That was the mantra for the movement. There was no hesitation. There was no debate. That was the rallying cry. And it was because that’s what we knew.”

Richardson said that one of the reasons the Black Lives Matters protests have taken off in such a big way is due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “You have a captive audience that for the first time is saying, hey, I know what it feels like to be shut out of something,” she said. “I’ve been shut out of society. I can’t work. There’s this invisible monster. I don’t know how to fight for the first time. Maybe most Americans began to see a little bit of what it’s like to be Black in America, to have that loss of control. That sensation of not controlling one’s destiny. Maybe that has made them more sensitive to this movement now.”

Aside from the sheer speed and magnitude of the current Black Lives Matter movement, online activism also seems to be offering more points of view this time around. “The framing is different now about what’s being filmed, and what’s being talked about,” said Richardson. For example, she said that we’re seeing an amplification of white disruptors and white agitators vandalizing property in a way that wasn’t really seen before. “When we think about the Rodney King riots, for example, we think of African-Americans destroying their own property. But now, for the first time, we have proof that this is not true; that there are infiltrators in the movement that run the gamut of who's out there.”

Another factor that’s different is that people are much more tech savvy. “People are talking about what are the things we should be thinking about when we expose this video,” Richardson said. “Like, should we [be] putting this out there? There’s a real attention to AI and how machine learning has accelerated the police’s ability to harass you for exercising your First Amendment rights.” As a result, there’s an explosion of apps and different features that people can use to blur their faces, for example, or use of encrypted text messages.

Richardson also appreciated that the social media conversations about systemic racism aren’t just about Black and white anymore. “Racism can come not just from white people,” she said. “You can have White Karens and Asian Karens and Latino Karens. Blackness as a whole is a sentiment that many people hold [...] The fact that there are so many anti-racism books at the top of the bestseller list means that not just white people are buying them. I’m assuming many people from different groups are examining their own biases as well.”

Of course, social media activism has its downsides, too. There’s the danger of so-called slacktivism, which is a way of showing support for a cause with minimal effort, often as a way to soothe egos or boost your own profile. An example of this is the Black Out Tuesday kerfuffle, where Instagram users posted black squares on their feed with the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag. Critics said that not only is it pointless, it also drowned out the hashtag search page with black squares, making it harder to find valuable information about the movement. Recently, several white celebrities were also called out when they participated in a rather vapid video montage where they “took responsibility” for perpetuating racism.

The reason such slacktivism is harmful is that it speaks to white privilege. “My problem with slacktivism is that it does not give credence to what everyday racism is like, in the weight of that debt to Black people,” she added. “I would encourage everybody not to just post or read tweets or Instagram posts, but to find some ways to get involved. Whether it’s donating to an organization or listening to a friend of color, but asking them questions like ‘Have I been a friend to you?’ or ‘Are there times where I may have made an off-color joke that didn’t sit well with you?’ These are the kinds of conversations that will move us forward. There are so many different ways that activism takes form that doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the hashtag.”

On top of that, social media platforms can be venues for harm as well as good. “It depends on the platform’s willingness to deal with users who spread misinformation or incite violence,” Richardson said, though she does commend Twitter for its recent actions to fact-check the president. “The more neutral they are, the more harmful they become.”

Still, there are signs of hope. Not only has social media activism resulted in real awareness about police brutality and racial justice issues, it has also sparked off its own unique brand of protest, such as when K-pop stans drowned out White Lives Matter hashtags and, along with TikTok teens, inflated attendance expectations of Trump’s Tulsa rally.

It remains to be seen, however, whether all of this can last. “I think it’s possible that it can be sustained,” said McIlwain. “But as life goes back to business as usual post-pandemic, it gives me caution that we’ll go back to life as usual as well.”