Snapshot of financial health during peak COVID-19

We are two and a half months into the global Coronavirus crisis. Confirmed cases exceed seven million, and at least four-hundred thousand lives have been lost. Billions of people around the world have accepted restrictions on movement and business as the surreal “new normal” as health services struggle to flatten the curve. The secondary effects are starting to pile up, with estimates for the number of individuals falling back into poverty ranging between 50M to 500M, undoing decades of socioeconomic gains.

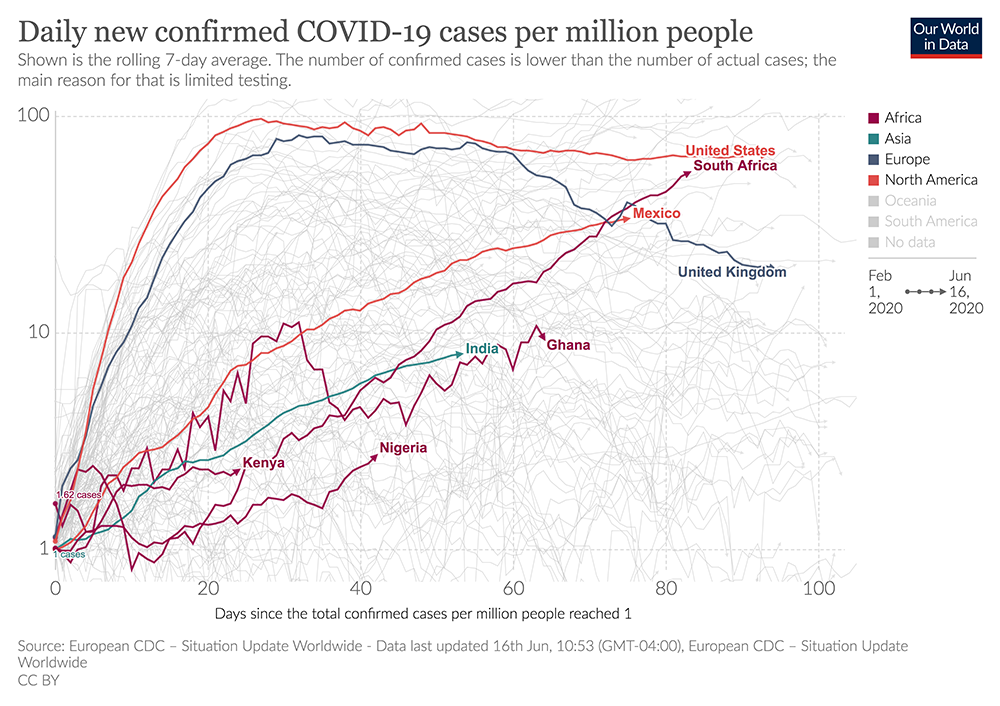

Today, the debate rages across countries on how to relax restrictions before livelihoods are irrevocably decimated, even though the pandemic was not quite under control yet (Figure 1). It is in this context that we conducted the third wave of our rapid online “dipstick” surveys in nine countries, polling 1,813 low- and lower-middle-income respondents in Ghana, India, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, South Africa, the UK, the US, and Vietnam [1].

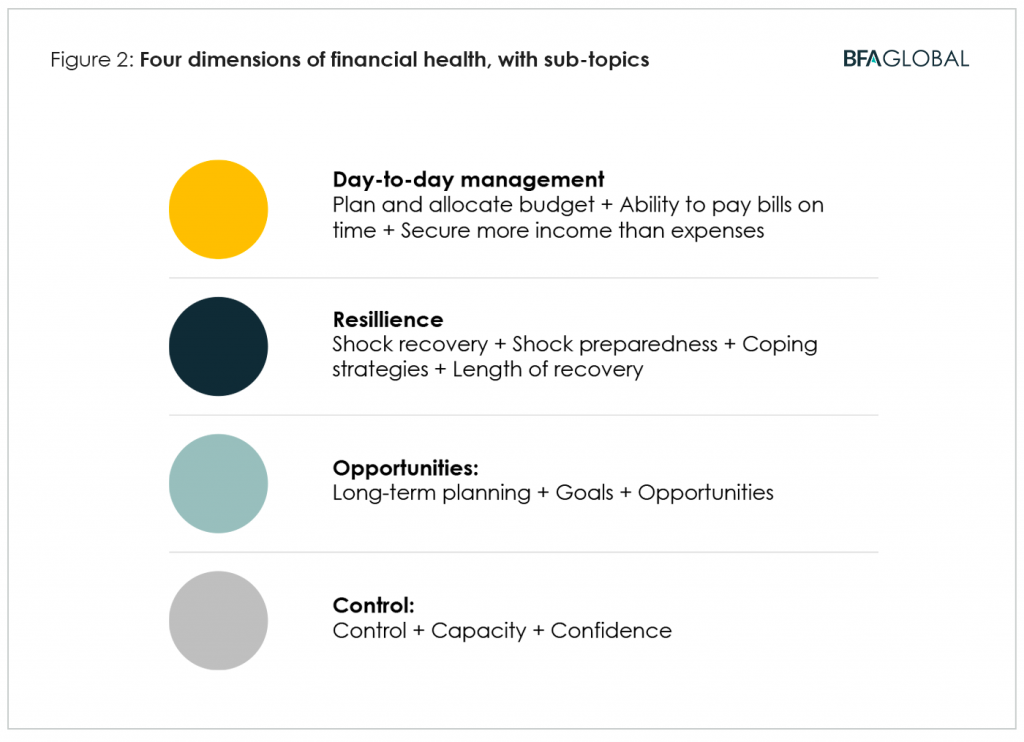

In this blog post, we present the summary findings from Wave 3, as well as comparisons to Wave 2, utilizing the financial health lens (Figure 2) to map the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on financial lives. We find that:

- Income has decreased and expenses have increased for half of the respondents. Most who have loans indicate current and future inability to service outstanding debt.

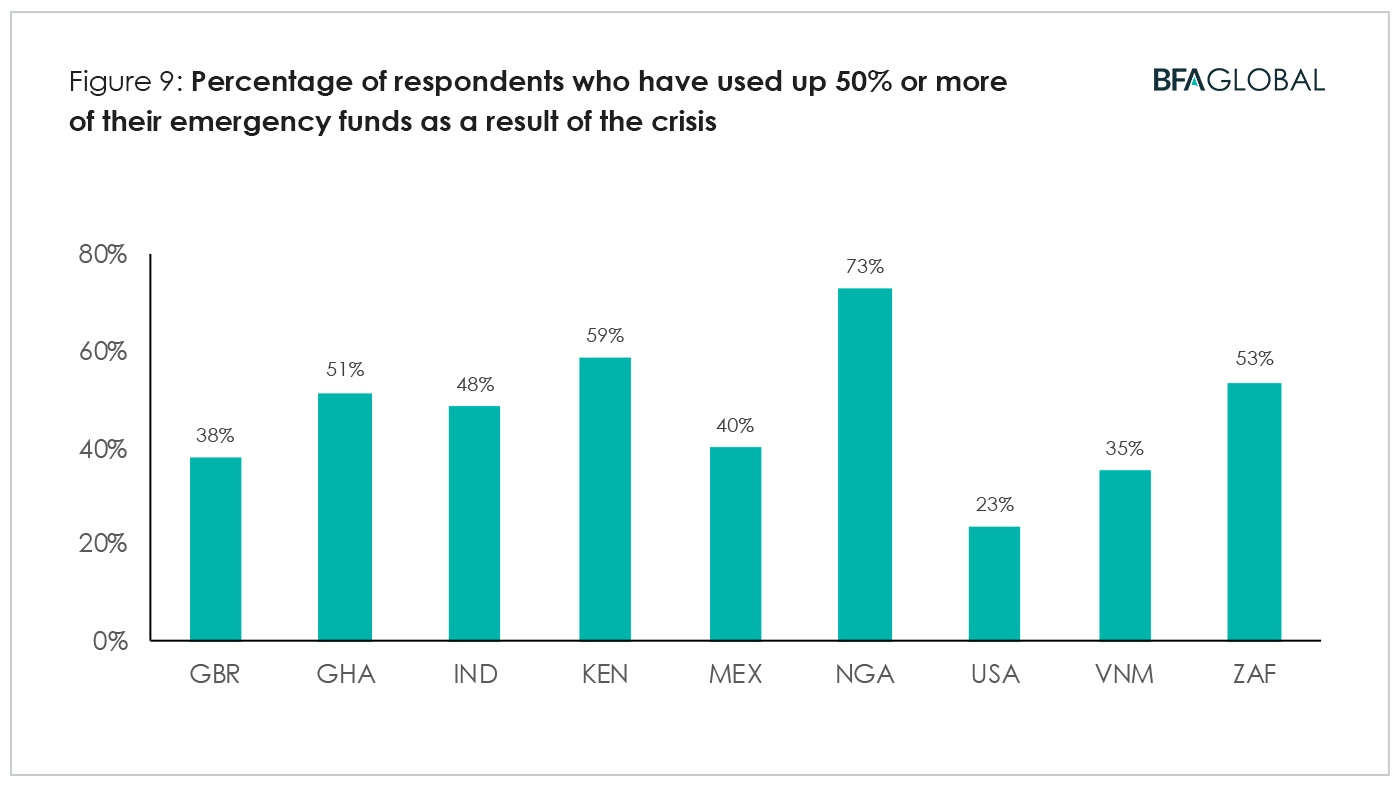

- Respondents in Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa, Ghana and India are running out of their financial cushion quickly, having used up more than half of what they had put away as emergency funds, as a result of the crisis.

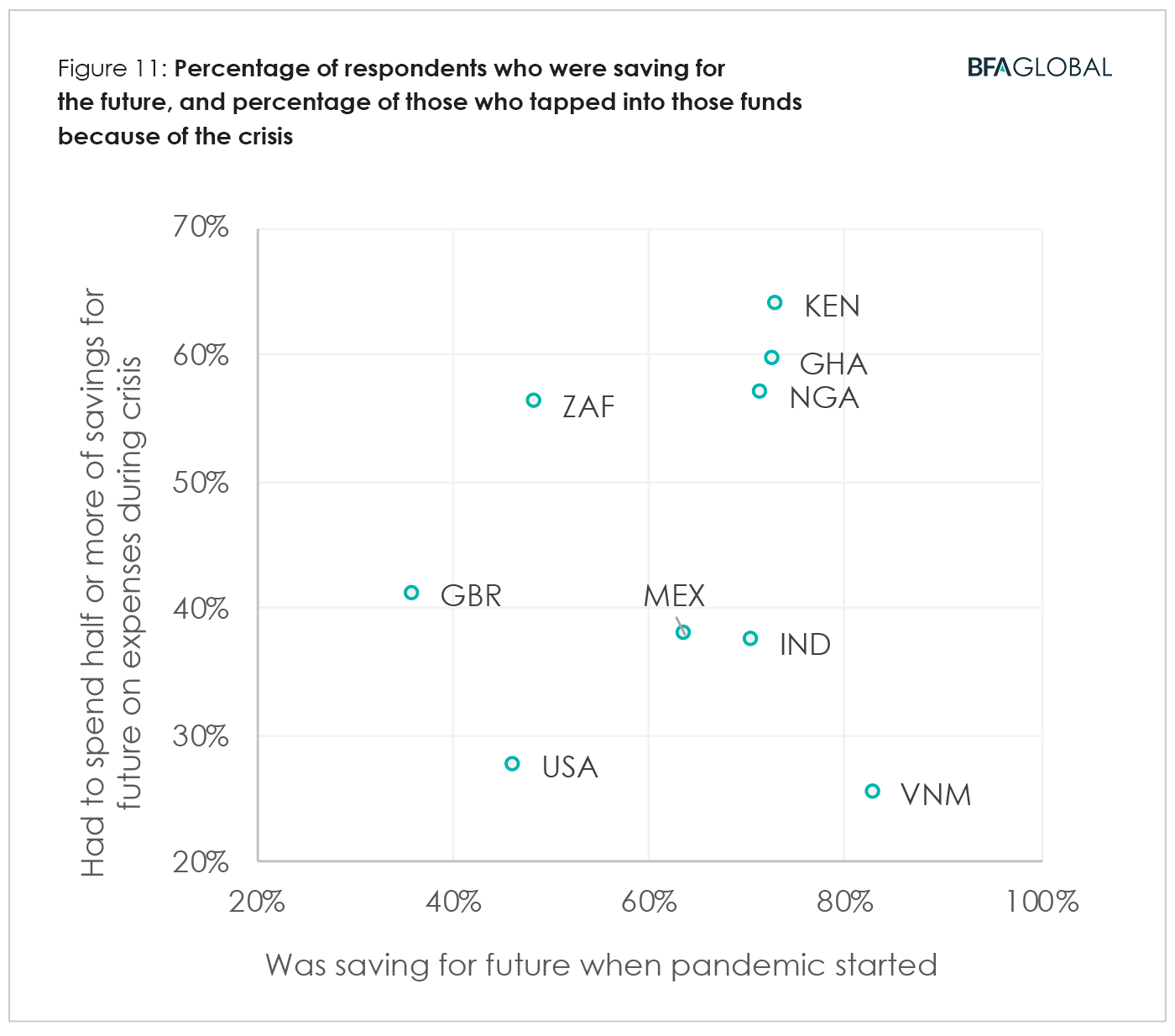

- About two-thirds of respondents in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa have tapped into funds that were earmarked for future planned or opportunistic use, and used up more than half of it.

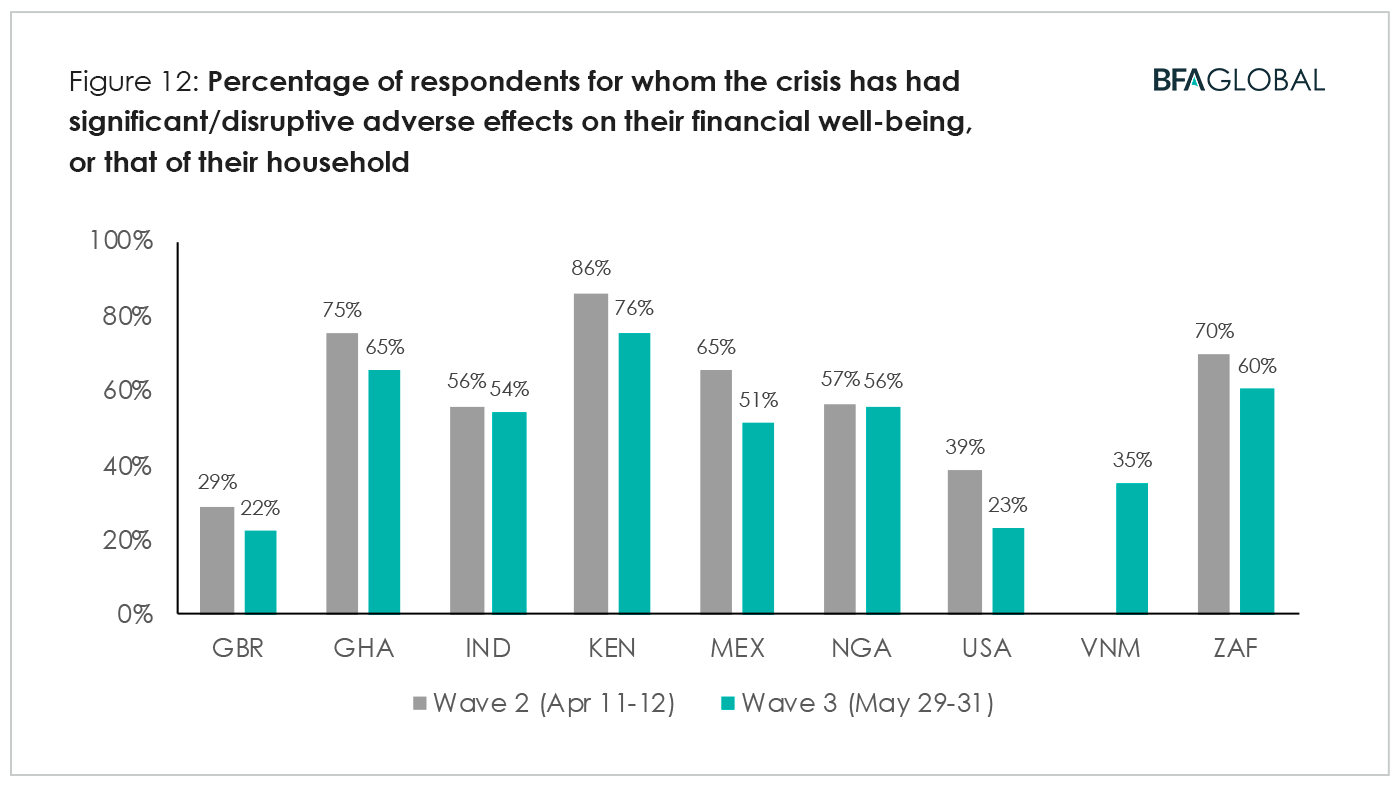

- More than half of the respondents in six of the nine countries believe that the crisis will have significant/disruptive adverse effects on their financial well-being, or that of their household, though the proportion has decreased since Wave 2.

Countries with the most severe lockdown measures, therefore, seem to have been significantly adversely affected.

Day-to-day financial management

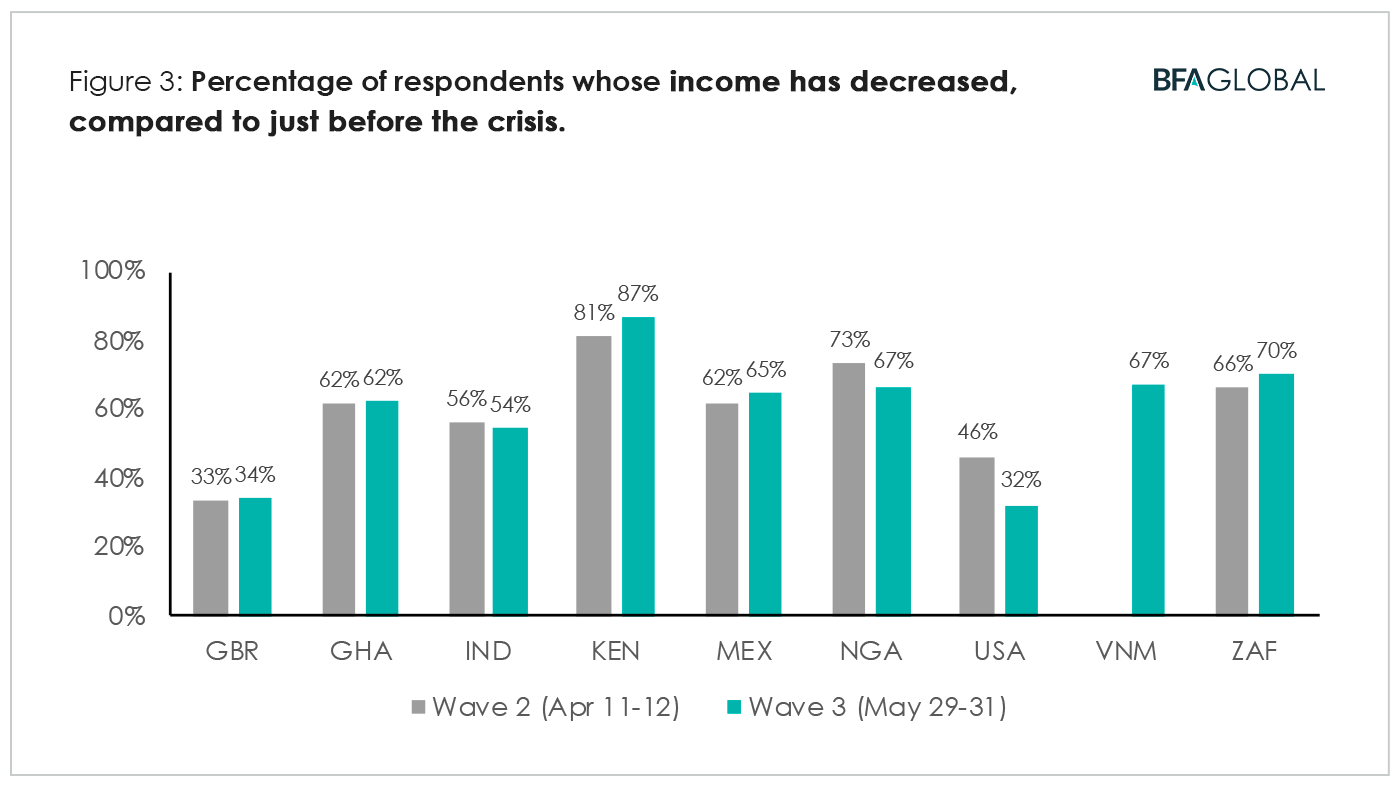

On a day-to-day basis, financial health is in part the ability to align expected incomes and expenses. COVID-19 has thrown households’ net income into disarray. Apart from the UK and the US, income has decreased for over half of the respondents (Figure 3). Kenya has the highest proportion of individuals whose income has decreased (87%). Incomes are still down today, as compared to pre-crisis levels, for just as many respondents as was the case in mid-April. Only the US has seen a meaningful improvement in this measure.

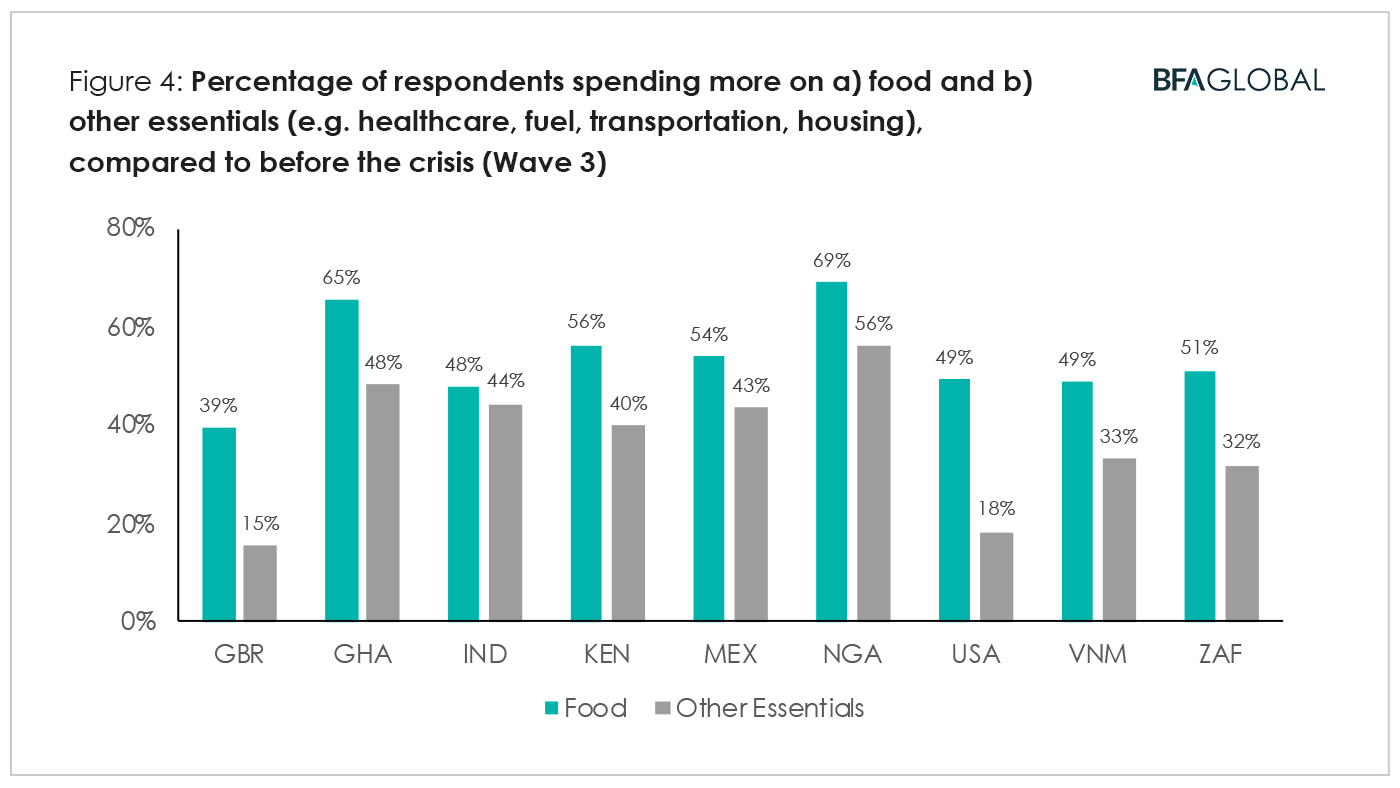

Expenses have increased for about half the respondents, too (Figure 4). About half to two-thirds of respondents in most countries spent more on food, compared to before the crisis. Most of this was a result of stocking up at higher levels. About a third to half of the respondents also increased spending on other essentials, such as healthcare, fuel, transportation and housing.

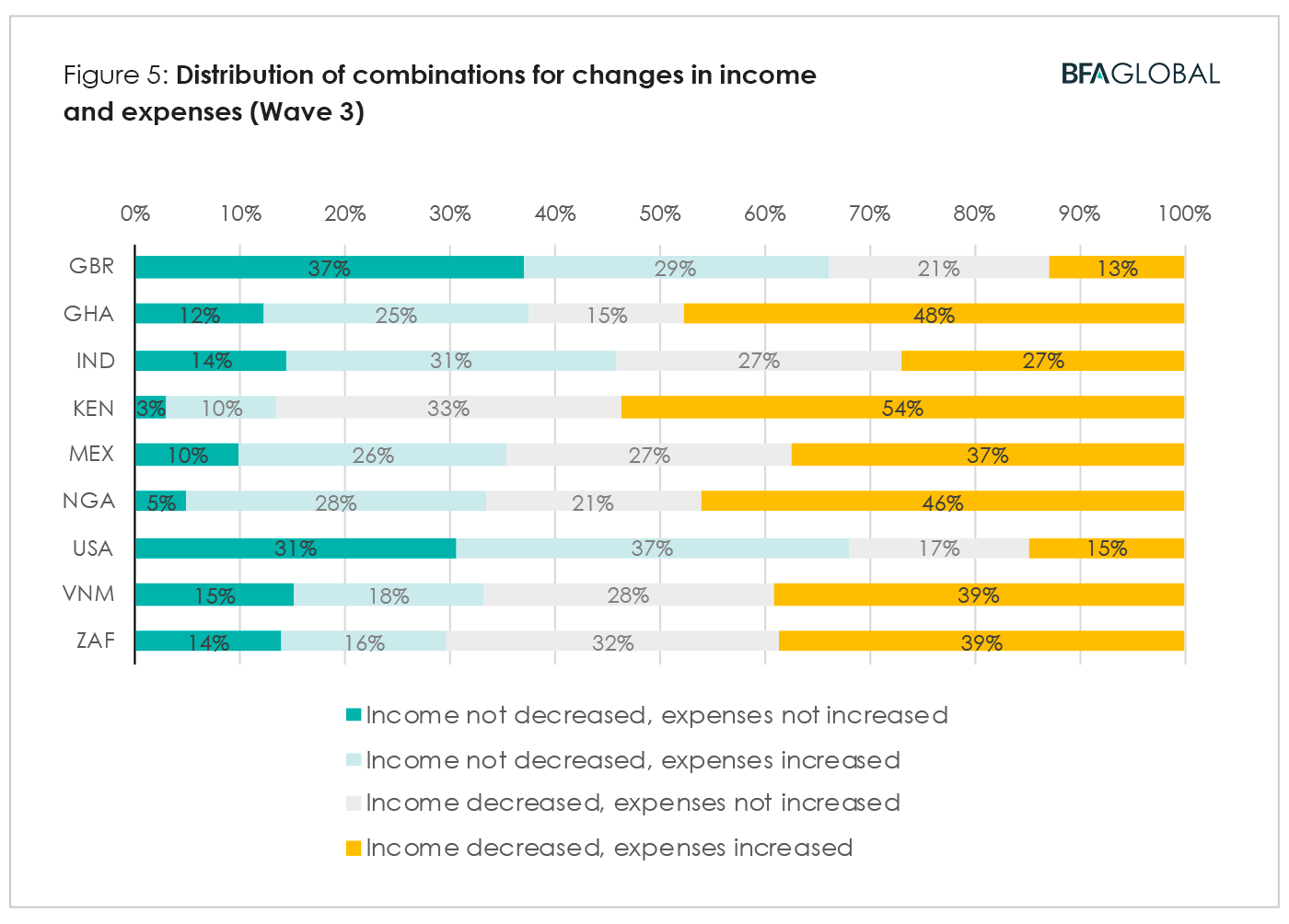

We can think of the net impact on the household budget as facing pressure from reduced incomes, from increased expenses, or both. The dual pressures from declining incomes and rising expenses are most acute in Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria, where roughly half of the respondents report both (Figure 5). More than a third of the respondents in Mexico, South Africa and Vietnam share the same fate.

Even in the UK and the US, stable or rising incomes and flat or declining expenses are enjoyed by only a third of respondents. Very few, therefore, seem to have escaped the downward pressure of COVID-19 on day-to-day finances.

The ability to service one’s debt obligations regularly and on time is an important determinant in financial health. COVID-19 has had a range of impacts on this dimension.

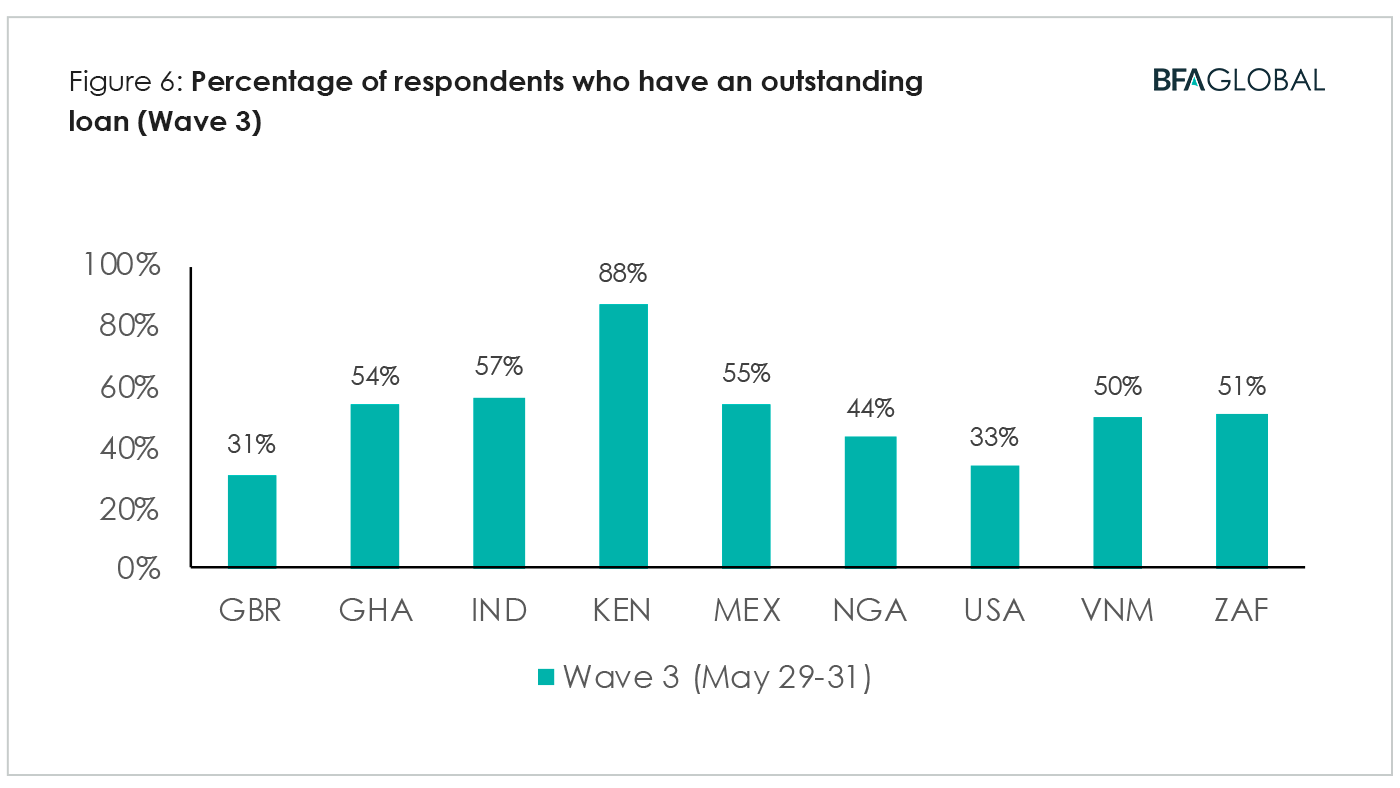

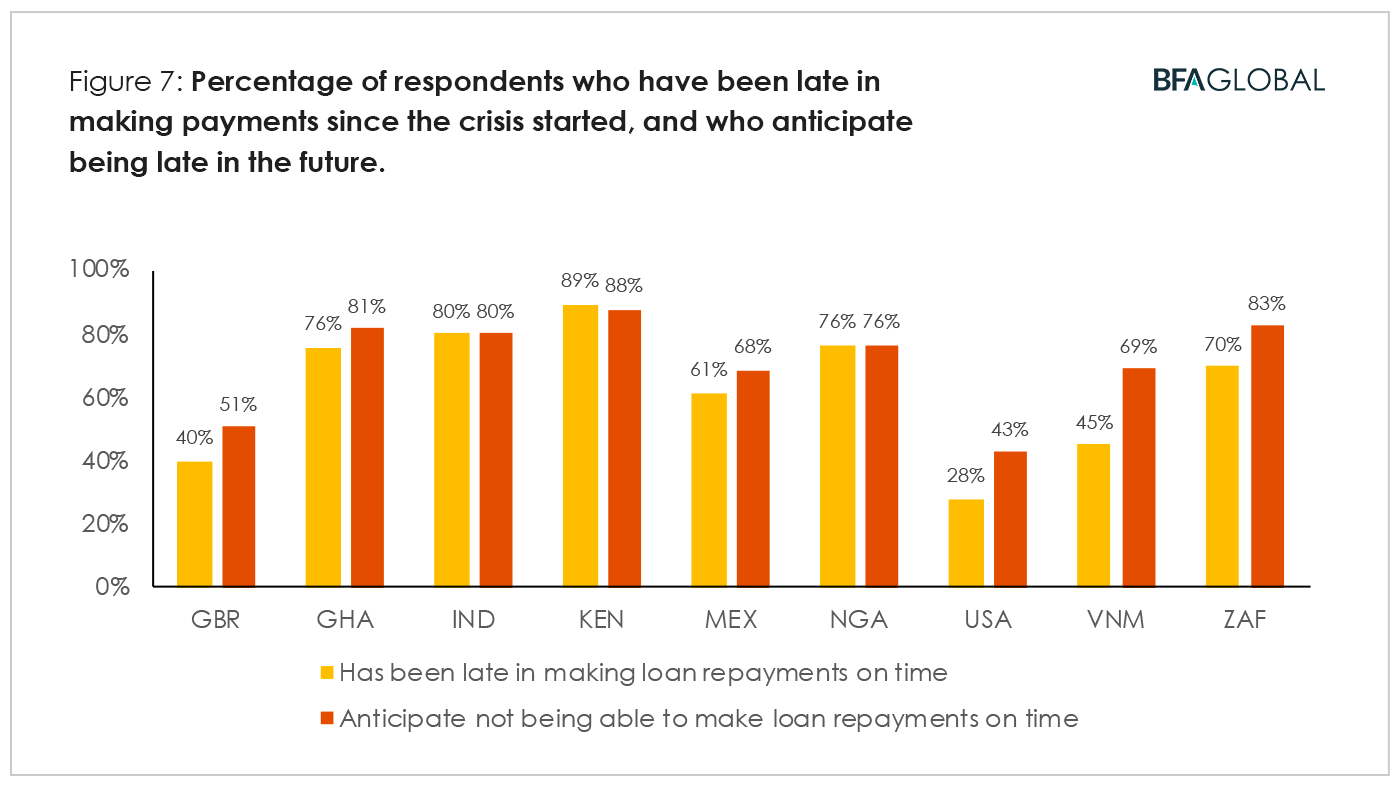

Kenyans are the most distressed by debt, with 88% reporting that they have an outstanding loan (Figure 6). Late payments are commonplace among borrowers, with approximately 88% also reporting that they have been late in making payments since the crisis started, and anticipate being late in the future as a result of it (Figure 7).

Consumer loan delinquencies will rise in the coming months, according to our respondents. Half of the respondents in Ghana, India, Mexico, Nigeria, Vietnam and South Africa have outstanding debts, and two-thirds or more indicated chronic delays in loan servicing during the times of COVID-19 (Figure 7). This points to the need for loan forbearance programs, and also paints a dire picture for financial service providers lending to the low- and lower-middle-income segments.

Financial resilience

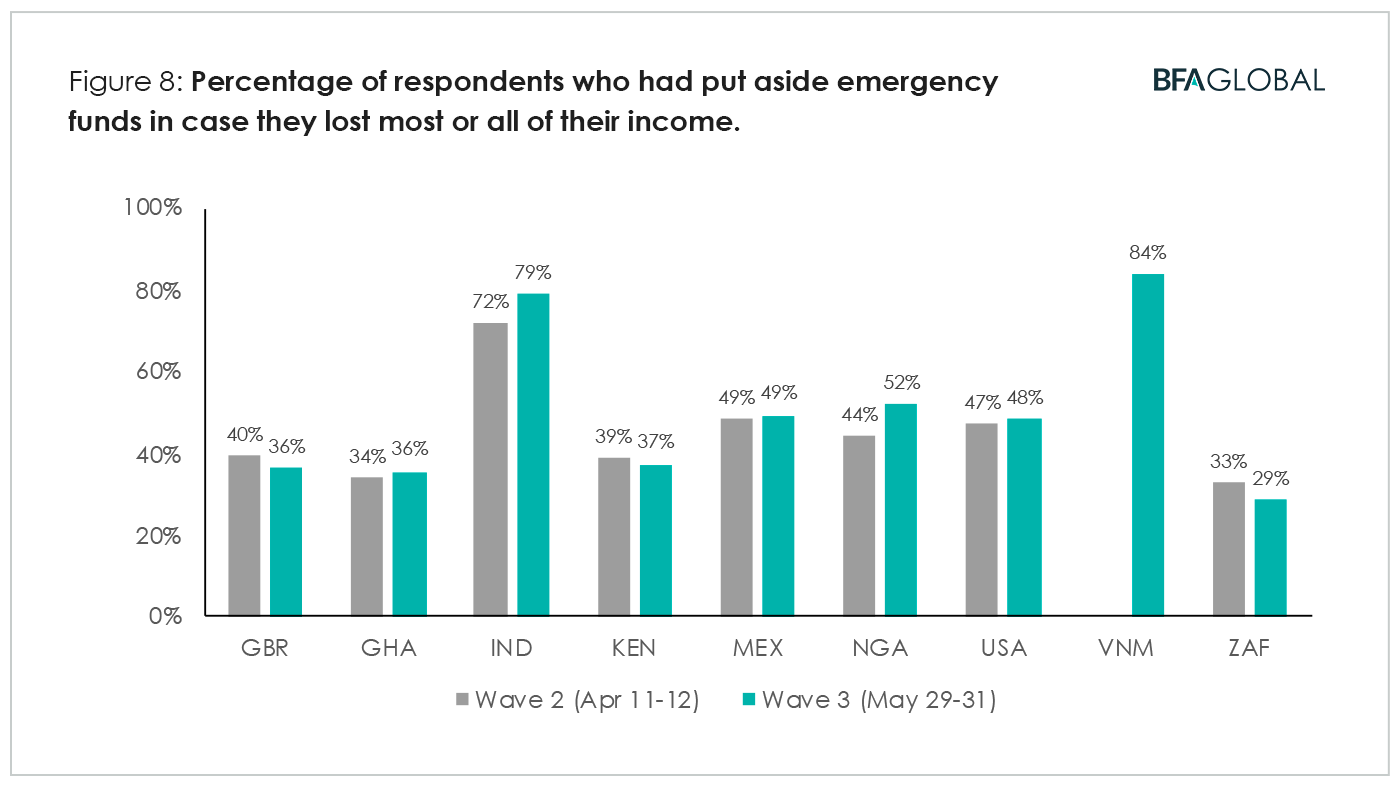

Resilience with regards to financial health assumes that one has built a meaningful lump sum to hedge against shocks. Vietnamese and Indian respondents were most likely to have put aside emergency funds in case they lost most or all of their income; South African respondents were least likely (Figure 8). Interestingly, there is very little change to this figure over the six weeks between Waves 2 and 3.

The degree to which these funds were drawn down to deal with the crisis varies by country.

Nigerian respondents had spent the most, with 73% of respondents noting that they have used up to half or more of their emergency funds (Figure 9). At the other end of the spectrum, only a quarter of the respondents in the US noted spending at least half of their emergency funds.

Overall, populations in Ghana, India, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa seem to be running out of their financial cushion quickly.

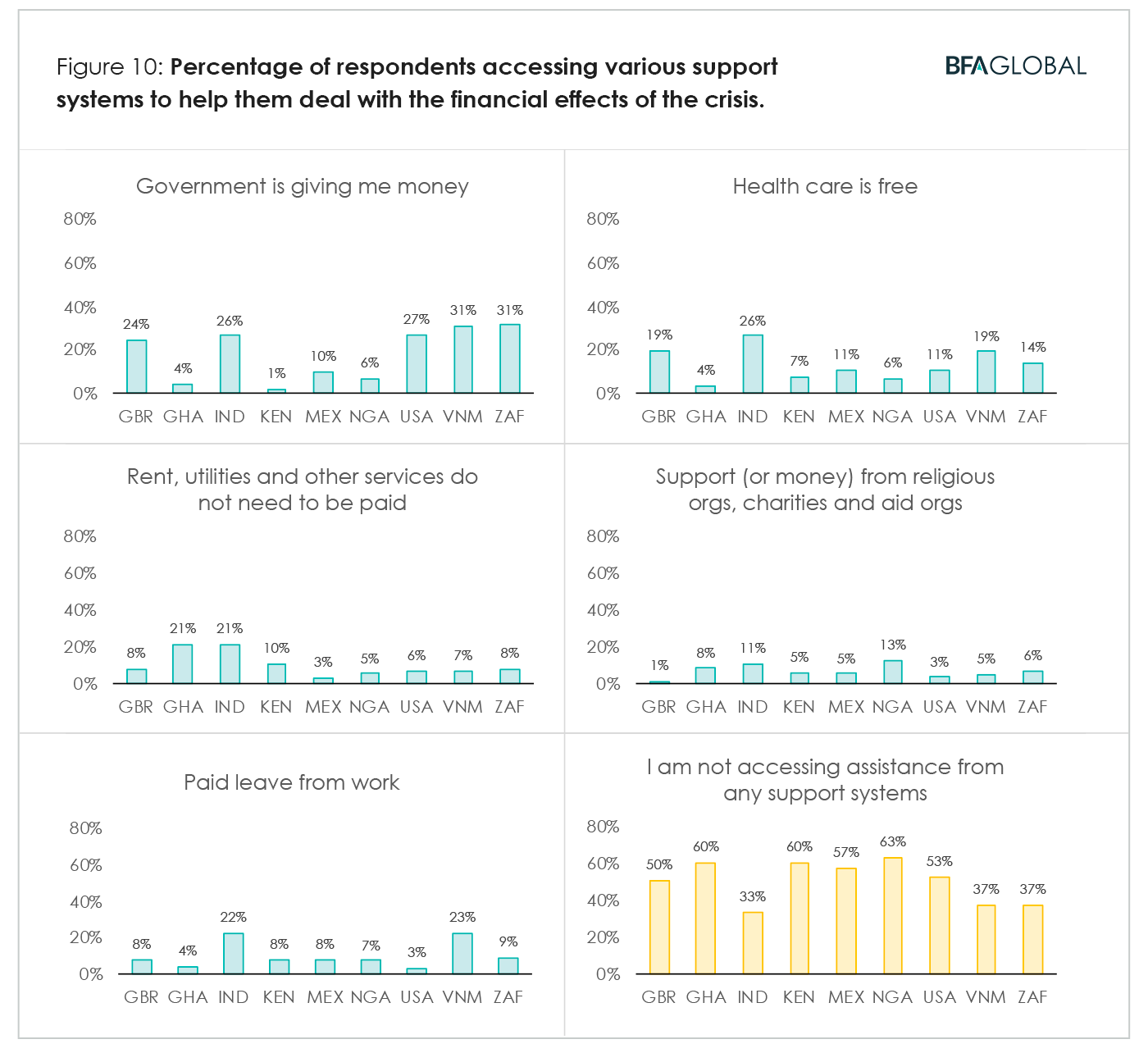

Given the global scale of this crisis, various government, non-government, and private sector players have come forward to provide assistance to the distressed. In many cases, this can take the form of financial safety nets, such as cash transfers, covering of expenses for essentials, and deferment of financial obligations. We find that two-thirds of respondents in India, Vietnam, and South Africa are receiving some form of assistance – the majority of the respondents in other countries are not (Figure 10).

Diverting funds for the future

Money is fungible. As a result of the crisis, many are being forced to tap into funds they had saved up to take advantage of investment opportunities or to pay for significant planned expenses in the future (Figure 11).

About two-thirds of the respondents in Kenya, Ghana and Nigeria were saving up for the future – about two-thirds of those have tapped most of those funds as a result of the crisis. Vietnam has the lowest incidence of use of funds earmarked for the future, very probably because the crisis was least acute there, compared to the other eight countries.

However, while money may be fungible, the impact of liquidating funds mentally mapped to fulfilling future goals represents a disruption in financial planning, unlike liquidating funds earmarked for emergency use, where the use is as intended. Will it be children’s education that will be impacted? Or the opening or expansion of a business? Or the purchase of livestock and farm inputs? Because it is exceedingly difficult for lower-income households to maintain the discipline to build a lump sum, it will be important to identify which investment objectives were disrupted once the worst of the crisis passes, and to facilitate getting them back on track toward those goals.

Staying in control

At a personal level, a financial crisis is as much a test of mental fortitude, as it is of pecuniary means. A feeling of agency is necessary to maintain that fortitude. Reliance on one’s agency, in turn, is affected by how they assess their status within the context of the crisis, as well as their prognosis for recovery. It is, therefore, encouraging to see that in the last six weeks, the proportion of respondents who think the crisis will have significant/disruptive adverse effects on their financial wellbeing has gone down, or stayed the same (Figure 12). Despite this, more than half of the respondents in six of the countries still feel that there will be significant adverse effects, so there is no room to be complacent.

The plight of the self-employed

The differences between those who are self-employed and those who have jobs are not numerous, other than for Nigeria (Table 5). This may very well be because job-holders may no longer be getting paid, or may even have lost their jobs, adding to their own distress from income-shock. Note that we excluded retirees, students, and homemakers from this comparison.

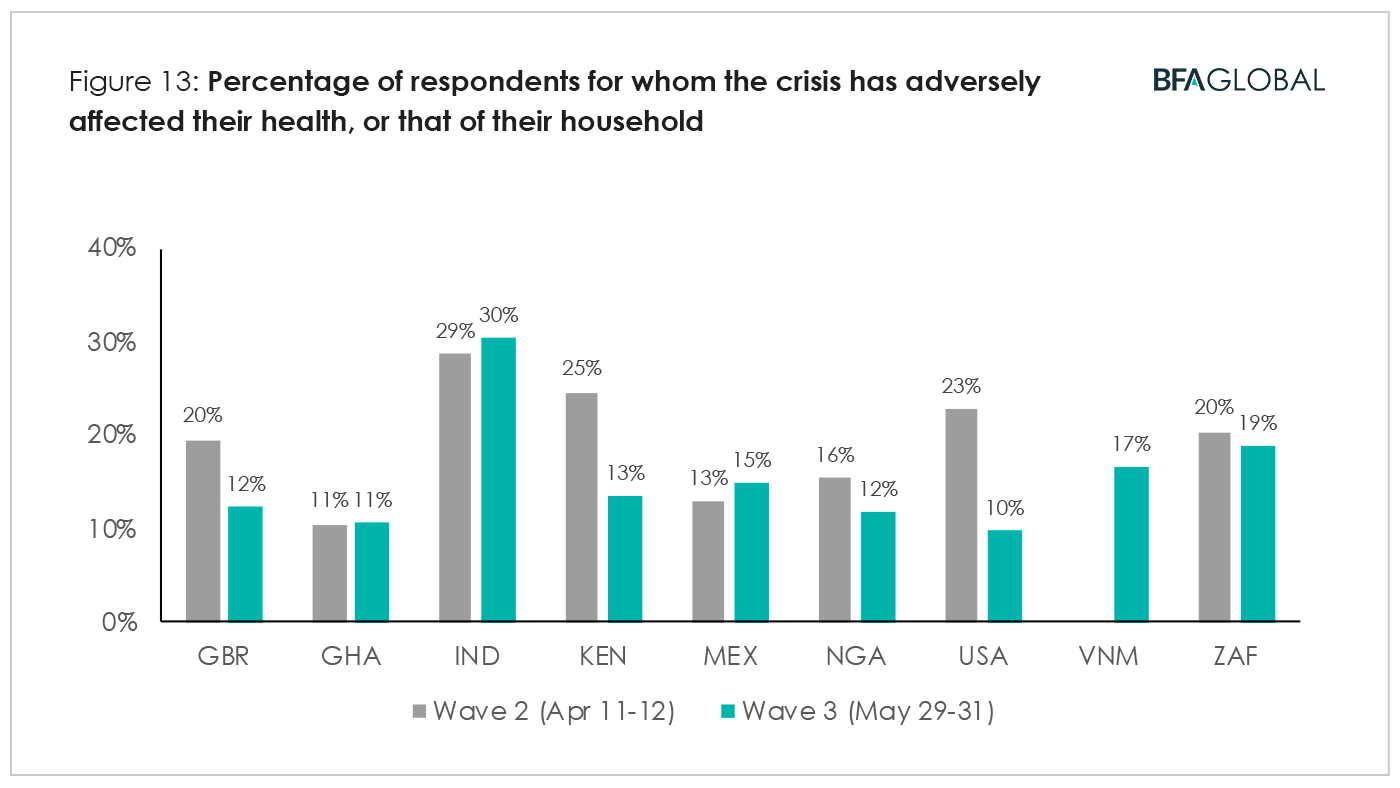

In comparison, the proportion of respondents who believe that their physical health has been adversely affected is in the teens, except for in India (Figure 13). There has been a marked decrease in concerns in Kenya, the UK and the US, with about half as many respondents registering concern during Wave 3, compared to Wave 2. Note that this query refers to any physical health, and is, therefore, picking up effects from an overburdened health system, unavailability of elective or routine procedures, and possibly even side effects of being in lockdown.

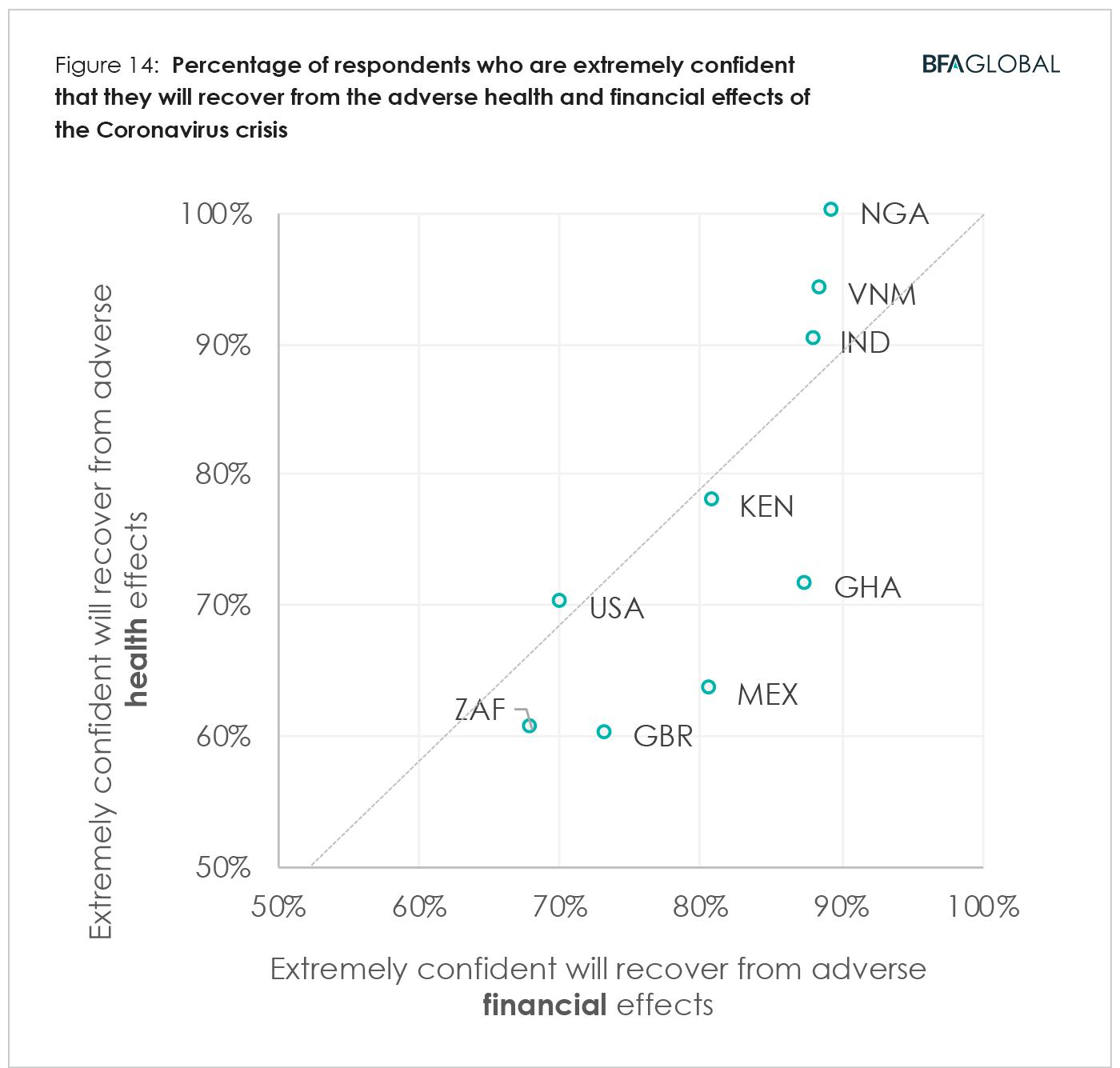

Expectations on recovery from significant adverse effects seem to go in lock-step, with respondents in Nigeria, Vietnam and India being most confident (Figure 14). Respondents in Ghana, Mexico and the UK are more confident about recovering from financial effects, than from health effects.

Utility of financial health as a framework during COVID-19

The pandemic has had far-reaching implications for financial health in these nine countries after just two months, and we have found that all four dimensions of financial health are under pressure. Income has decreased and expenses have increased for many, and most with outstanding loans indicate difficulties in servicing that debt. Respondents are running out of emergency funds to tap into, and are also liquidating funds earmarked for the future. And most respondents continue to expect significant adverse financial effects, though the proportion of that has not worsened. On average, then, it seems that the lines are holding in some areas of financial health while being significantly stressed in others.

At the conceptual level, the three survey waves over two months allowed us to test the applicability of financial health as a framework within a rather novel context. Over the last couple of years, the financial inclusion industry embraced financial health as a preferred customer-centric approach to ensure that benefits followed inclusion, leading to improvements in quality of life. In contrast, COVID-19 is quite like a natural disaster, where the focus is on preservation and resilience, to prevent a deterioration in the same quality of life. Despite this change in focus, we find that the four dimensions of financial health continue to provide great utility, as we adapt the questions we ask and the implications we explore to the reality of COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The deployment of Wave 3 in Mexico and Vietnam and overall analysis was supported by the Metlife Foundation. We are grateful for the Foundation’s support as we continue to apply financial health as a framework to understand financial lives under a variety of circumstances.

[1] Wave 3 was conducted during the last week of May and the first week of June. The samples were balanced by age and gender. Vietnam was added to Wave 3, and therefore does not have data from prior waves. Wave 2 was conducted a month and a half earlier, roughly two weeks after stringent restrictions were imposed in India, Kenya, Mexico, and South Africa, and one week before, for Nigeria.