The Shrinking of the American Lawn

As houses have gotten bigger, yard sizes have receded. What gives?

The American house is growing. These days, the average new home encompasses 2,500 square feet, about 50 percent more area than the average house in the late 1970s, according to Census data. Compared to the typical house of 40 years ago, today’s likely has another bathroom and an extra bedroom, making it about the same size as the Brady Bunch house, which famously fit two families.

This expansion has come at a cost: the American lawn.

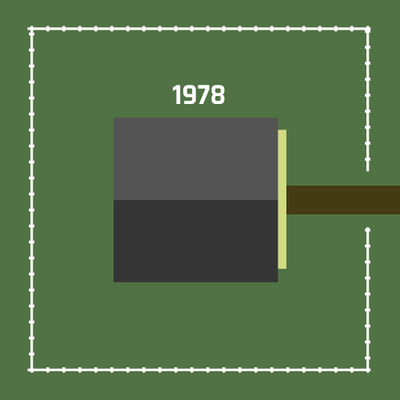

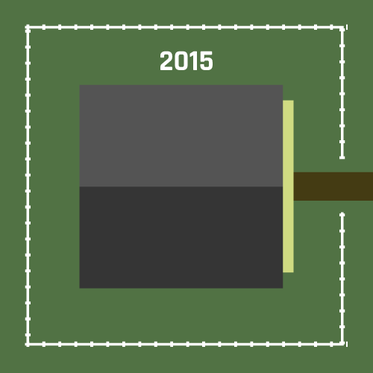

The first diagram shows what the average house looked like in 1978, when it measured 1,650 square feet and sat on 0.22 acres. The second shows its counterpart from 2015.

As homes have grown larger, the lots they’re built on have actually gotten smaller—average area is down 13 percent since 1978, to 0.19 acres. That might not seem like a lot, but after adjusting for houses’ bigger footprints, it appears the median yard has shrunk by more than 26 percent, and now stands at just 0.14 acres. The actual value lies somewhere between those two numbers, since a house’s square footage could include a second (or third) floor. Either way, it’s a substantial reduction.

And this is data on new homes. No one is going door-to-door and lopping off front lawns (well, except for where they are). The truth is far more sinister: Americans are voluntarily buying houses with smaller yards. What does the United States stand for, if not the right to a fertile, springy carpet of turf thicker than the Bradys’ wall-to-wall shag?

At first, I wondered if lawn shrinkage could be due to a growing interest in building “attached” homes—townhomes, duplexes, any residence that shares a wall with a neighbor. These residences, popular in cities and inner-ring suburbs, offer far less yard space than stand-alone houses, though plenty of square footage. Alas, Census data indicates that 90 percent of new homes sold in 2015 were “detached,” indicating almost all growth came from more traditional structures. Theory dashed.

Could this be a regional thing? Perhaps cramped lots are the result of more construction in the crowded Northeast, where land is expensive. Nope: New-home construction fell sharply in the northern I-95 corridor during the recession and hasn’t recovered since. It’s the South that has seen the biggest building boom, and land there is still pretty cheap. And indeed, a 2015 Zillow report found that yards are shrinking across the southern states and the Great Plains, despite a surplus of room to expand.

That same report posits the shrinking lawn is actually an economic compromise. Americans want bigger houses, but since every additional square foot balloons the cost, homebuilders are keeping prices affordable by cutting off lawn acreage.

From Svenja Gudell, the chief economist at Zillow:

“We still want our big homes with ample bedrooms and bathrooms, but increasingly, we’re having to make a tradeoff to keep those kinds of homes accessible—namely, smaller lots. Americans want both space and convenience, but the land available relatively close to job centers is expensive. This trend of larger homes and smaller lots represents the compromise between what builders can profitably build and what consumers will actually buy.”

Forced to choose between having a bigger lawn and a bigger house, Americans who live near economic hubs are picking the house.

The cultural primacy of the lawn has other enemies, too. As my colleague Megan Garber noted last year in “The Life and Death of the American Lawn,” a mix of drought-conscious environmentalism and shift in social mores has made spending money and effort on perfectly tufted turfgrass seem a bit simpering, even selfish. “Maybe, as the billboards dotting California’s highways cheerily insist, ‘Brown Is the New Green,’” she wrote. Witness the rise in rock gardens and drought-resistant yards.

An inflection point approaches. For now, a lawn is still an end in itself, a place to play and garden and stick pink flamingos. But if the shrinkage continues, the lawn is in danger of becoming merely symbolic. That’s nothing new to city dwellers, who count themselves lucky to have a patch of grass and have made public parks their front yards for centuries. But it would signal a profound change in suburbia, and not an altogether attractive one, as McMansions squeeze ever tighter together, hulking and lonely.