What are the most important talent gaps in the effective altruism community?

Fan art for the Disney Film, The Sword and the Stone, by Murph3

Note that this article is from 2017. For more up-to-date findings, see our new 2018 survey, which asked most of the same questions and some additional ones.

Update April 2019: We think that our use of the term ‘talent gaps’ in this post (and elsewhere) has caused some confusion. We’ve written a post clarifying what we meant by the term and addressing some misconceptions that our use of it may have caused. Most importantly, we now think it’s much more useful to talk about specific skills and abilities that are important constraints on particular problems rather than talking about ‘talent constraints’ in general terms. This page may be misleading if it’s not read in conjunction with our clarifications.

What are the highest-impact opportunities in the effective altruism community right now? We surveyed leaders at 17 key organisations to learn more about what skills they need and how they would trade-off receiving donations against hiring good staff. It’s a more extensive and up-to-date version of the survey we did last year.

Below is a summary of the key numbers, a link to a presentation with all the results, a discussion of what these numbers mean, and at the bottom an appendix on how the survey was conducted and analysed.

We also report on two additional surveys about the key bottlenecks in the community, and the amount of donations expected to these organisations.

Table of Contents

- 1 Note that this article is from 2017. For more up-to-date findings, see our new 2018 survey, which asked most of the same questions and some additional ones.

- 2 Key figures

- 3 Want to work at one of the organisations in this survey?

- 4 Full analysis

- 5 What do the results mean?

- 5.1 EA leaders report significant talent gaps

- 5.2 EA leaders believe that giving focussed on the EA community and long term future is more effective than that on global poverty or animal welfare

- 5.3 If it’s safe, you could consider moving forward some donations

- 5.4 What kinds of talent do we need more of?

- 5.5 How do the results compare to last time?

- 5.6 Weaknesses of the survey

- 6 What’s the key bottleneck for the effective altruism community?

- 7 How fast will donations to meta-charities grow over time?

- 8 Acknowledgements

- 9 Appendix 1 – How the talent survey was conducted and analysed

- 10 Appendix 2 – Answers to open comment questions

Key figures

Willingness to pay to bring forward hires

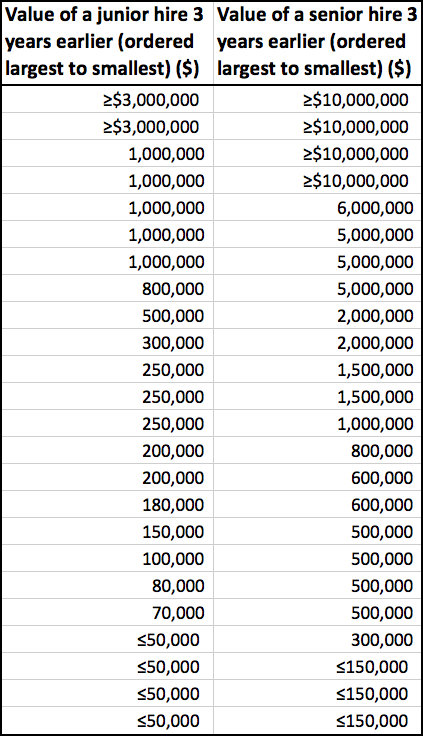

We asked how organisations would have to be compensated in donations for their last ‘junior hire’ or ‘senior hire’ to disappear and not do valuable work for a 3 year period:

| Average weighted by org size | Average | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senior hire | $12.8m ($4.1m excluding an outlier) | $7.6m ($3.6m excluding an outlier) | $1.0m |

| Junior hire | $1.8m | $1.2m | $0.25m |

Most needed skills

| Skill | My org | EA as a whole | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good calibration, wide knowledge and ability to work out what's important | 20 | 21 | 41 |

| Generalist researchers | 20 | 13 | 33 |

| Management | 15 | 18 | 33 |

| Government and policy experts | 6 | 23 | 29 |

| Operations | 10 | 13 | 23 |

| Machine learning / AI technical expertise | 9 | 14 | 23 |

| Movement building, public speakers, public figures, public campaign leaders | 8 | 14 | 22 |

- Decisions on who to hire most often turned on Good overall judgement about probabilities, what to do and what matters, General mental ability and Fit with the team (over and above being into EA).

Funding vs talent constraints

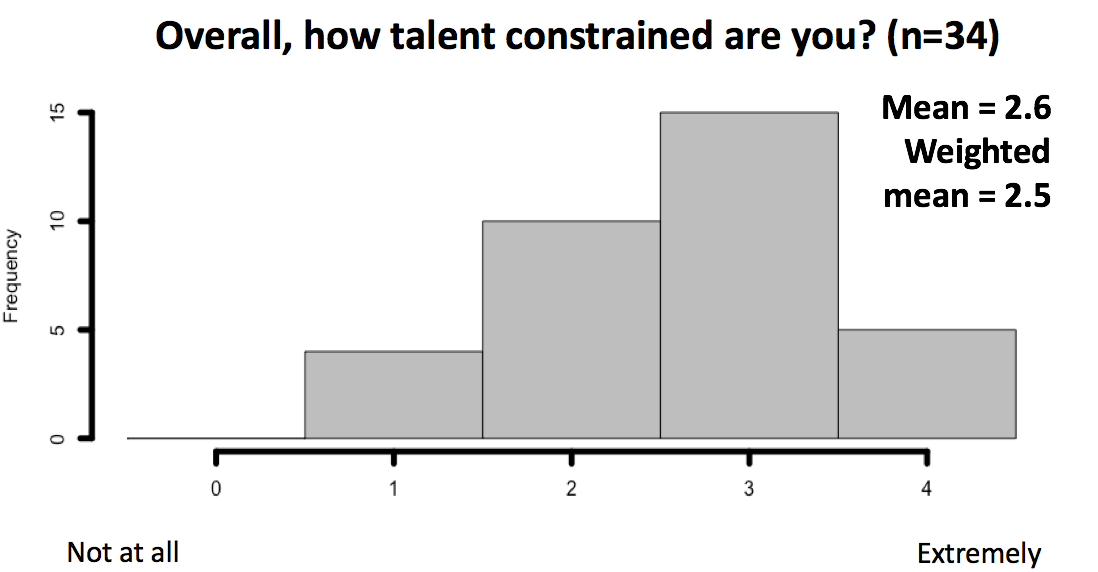

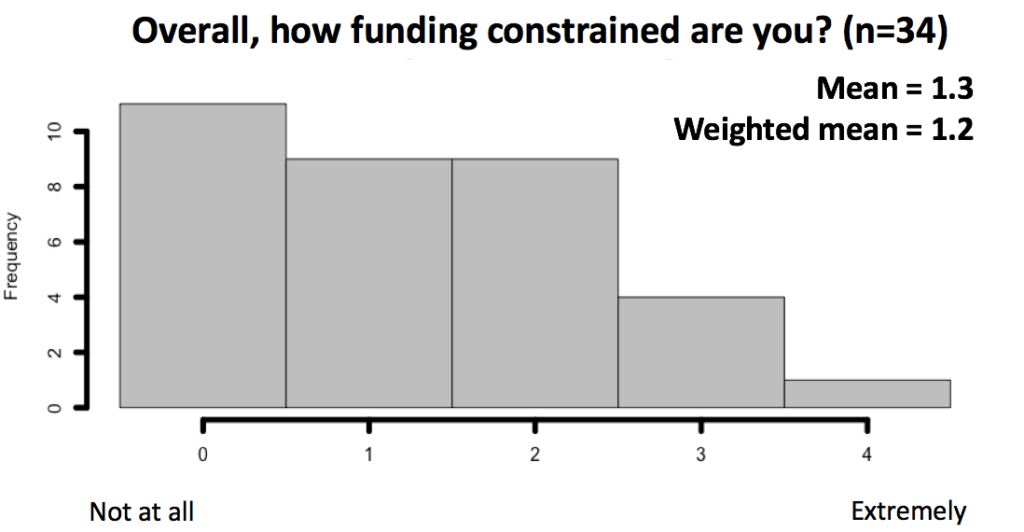

- On a 0-4 scale EA organisations viewed themselves as 2.5 ‘talent constrained’ and 1.2 ‘funding constrained’, suggesting hiring remains the more significant limiting factor, though funding still does limit some.

- We tried probing the same issue another way: organisational leaders thought doubling their funding over the next 3 years (relative to it staying constant) would allow them to do 28% more good while doubling their quality-adjusted pool of applicants would have allowed them to do 49% more good (relative to it staying constant). (Both figures there are for a size-weighted average).

- Considering the next 3 years, the median organisation had a time discount rate on donations of 14% per year. That is, they valued a $100 donation now as much as a $114 donation next year.

- 22 donors who are ‘earning to give’ were surveyed on how much they expect to give in future – their expected donation growth rate was 28% per year for the next five years.

Relative effectiveness of working to solve different problems

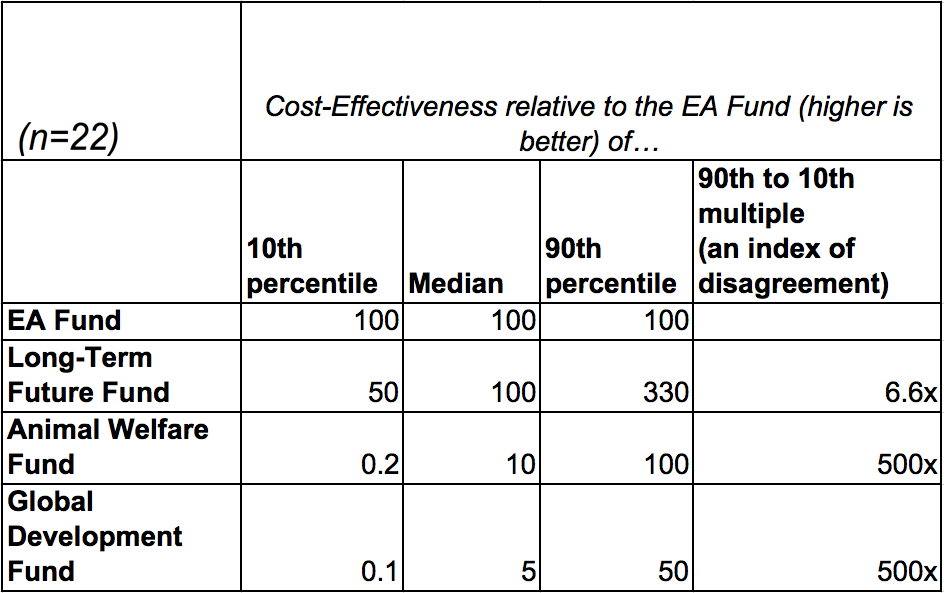

- We asked leaders their views on the relative cost-effectiveness of donations to 4 different funds being operated by the community – one focussed on Global Development, another on Animal Welfare, another on growing the Effective Altruism Community, and another on improving the Long-Term Future.

- The median view was that the EA Community and Long-Term Future funds were equally cost effective, and in turn 10 times more cost-effective than the Animal Welfare fund, which was twice as cost-effective as the Global Development fund. Views were similar among people whose main research work is to prioritise different causes – none of whom rated Global Development as the most effective. However, individual views on these issues varied over five orders of magnitude (see below for details).

Want to work at one of the organisations in this survey?

Speak to us one-on-one. We know the leaders of all of these organisations and current job openings, so can help you find a role that’s a good fit.

You can also read more about these kinds of jobs.

Or find top vacancies at many of these organisations on our job board.

Full analysis

Many of the results are shown below. All the resulting tables are available in the following presentation.

Our goal was to include at least one person from every organisation founded by people who strongly identify as part of the effective altruism community with full-time staff, which we largely accomplished. The survey includes (number of respondents in parentheses): 80,000 Hours (3), AI Impacts (1), Animal Charity Evaluators (1), Center for Applied Rationality (2), Centre for Effective Altruism (3), Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (1), Charity Science: Health (1), Foundational Research Institute (2), Future of Humanity Institute (3), GiveWell (2), Global Priorities Institute (1), Leverage Research (1), Machine Intelligence Research Institute (2), Open Philanthropy (5), Rethink Charity (1), Sentience Institute (1) and Other (6) (who were mainly researchers). The survey mostly took place at the EA Leader’s Forum in Oakland in August 2017 – we then emailed the survey to groups that didn’t attend that forum to fill in the gaps.

The reader should keep in mind this sample does not include some direct work organisations that some in the community donate to, including the Against Malaria Foundation, Mercy for Animals or the Center for Human-Compatible AI at UC Berkeley.

The methodology is described in detail in Appendix 1. The weaknesses of the method are also discussed below. I’ve tidied up and anonymised the free text responses to four questions and put them in Appendix 2.

What do the results mean?

EA leaders report significant talent gaps

Many organisations reported being willing to give up large donations to retain their most recent hires. For a three year period, some gave figures over $10 million for a senior hire. For junior hires, the median was $250,000, but about a third gave figures over $500,000.

Here is the exact question we asked:

For a typical recent Senior/Junior hire, how much financial compensation would you have needed to receive today, to make you indifferent about one of them not having been available for you or anyone to hire for a further 3 years?

Here are the full results, which show a great deal of spread:

What can we infer from this?

First, we need to question whether the estimates are accurate. It’s very hard to make estimates like these, and the respondents didn’t have long to analyse the figures. You can see more discussion of the weaknesses of the survey later.

This said, it’s hard to know how to get better data on this question, and there are lots of examples of high figures, so it’s not the result of a few answers skewing the results.

To sense-check the figures, we also asked about talent constraints from two other angles. The answers we received support the general idea that EA organizations are more talent-constrained than funding constrained:

| We’d do X% more good for the world if we had… | ||

| (n=18) | 2x funding | 2x talent pool |

| Average | 36% | 48% |

| Weighted average | 28% | 49% |

| 10th Percentile | 4% | 22% |

| Median | 28% | 40% |

| 90th Percentile | 71% | 86% |

Why don’t those organistions that have money but can’t hire the people they need just offer to pay more money until they can? Respondents gave a wide range of answers to this, which you can read in questions 3 in appendix 2.

Supposing the tradeoff figures are correct, what does this mean for the value of direct work at these organisations?

If you think these organisations are among the best donation opportunities, then these figures reflect the value of new hires measured in donations to top charities. This suggests that many of the workers are having much more impact than they could by earning to give.

When might someone be in such a position to do particularly valuable direct work?

- You have excellent personal fit for the role — if you’re only marginally better than the person who would have been hired otherwise, the organisation won’t be willing to pay much extra.

You have an offer to work at one of the more talent constrained organisations, which tend to be the larger ones.

You have an offer to fill a relatively senior role — the figures are several times higher for senior roles on average.

You won’t require much effort to train and select. New hires are less valuable to the organisation than their most recent hire, since recent hires have already been vetted and trained to some degree. This means the figures are an overestimate of the value of marginal hires, unless you’re in a position to “hit the ground running” at the organisation.

These positions aren’t for everyone, but if you’re unsure about your own situation, then these results suggest there’s huge value in finding out whether you might be a good fit. If you are, then it’s likely your highest-impact option.

As a first step to learn more, read our profile about these jobs.

EA leaders believe that giving focussed on the EA community and long term future is more effective than that on global poverty or animal welfare

The median response about the cost-effectiveness of the different EA funds was the following:

The results weren’t noticeably different for the 9 dedicated global priorities researchers in the sample.

Looking at the 90th to 10th percentile range, there was a 3,000x range of relative cost-effectiveness. While there was a lot of agreement that the value of EA Community Fund and Long-Term Future fund was similar – which makes sense, since they’re both run by Nick Beckstead – there were wildly varying views on the value of poverty reduction and animal welfare.

On the other hand, if we look at the median view, there’s only a 20x difference between the most and least cost-effective funds.

To look at the results another way, we can see how many people thought each fund was the most cost-effective of the four (votes are split in case of a tie):

| Fund | Votes for this fund being most cost-effective | Votes for this fund being most cost-effective among global priorities researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Long-term future fund | 11.75 | 5.75 |

| EA community fund | 6.75 | 2.75 |

| Global development fund | 2.75 | 0.25 |

| Animal welfare fund | 1.75 | 0.25 |

Again it’s clear that the group had quite a strong preferences for EA movement building and work to improve the long term future.

These answers contrast with a survey of 1,450 people in the community at large, of whom 41% gave poverty reduction as thier ‘top priority’.

How much should a donor adjust their view of cause effectiveness based on these survey results? If they generally accept the effective altruist view of the world, I think quite a bit.

In my opinion the group surveyed included many of the most clever, informed and long-involved people in the movement. Most people in the group did not start out their work to improve the world by favouring the first two options – rather they passed through a phase of focussing on global development or animal welfare and subsequently changed their minds (including me).

Furthermore, as a rule of thumb, people are too reluctant to update based on the stated views of others rather than too enthusiastic.

However, there are a few reasons for caution. Firstly, the survey is not only about the four different cause areas, but also about four specific donor funds – the results may in part reflect people’s confidence in the fund managers themselves. Nick Beckstead has less other funding to support long-run future and effective altruism community building than either of the other two fund managers have to support their areas, which may make his marginal donations seem more valuable. Secondly, the survey is about marginal donations rather than average donations across the cause as a whole – it also doesn’t directly ask about the value of sending talented people into a field. Thirdly, the EA Leaders Forum necessarily had a high representation of people working to build the EA community as this was the main topic of discussion. A group that has chosen to work on community building can be expected to have an unusually positive view of the value of that work.

Explaining away the strong result for the long-term future fund is harder. One of the largest organisations – GiveWell – only gave one submission to this question, which may have suppressed support for their cause area (global development). On the other hand, many people not working in long-term focussed organisations nonetheless rated it as most effective.1

On balance I think these results are informative. But they would be even more persuasive if asked of a wider range of people conducting research within the EA community without any bias towards selecting people interested in a particular cause.

If it’s safe, you could consider moving forward some donations

While the size-weighted average discount rate for donations was 12%, a number of respondents replied suggesting that their organisation’s discount rate on future donations was quite high (>20%). That is to say, they benefit significantly more from a donation now than the same donation guaranteed to arrive in a year’s time.

| List of all the donation discount rates given by respondents in the survey ordered from largest to smallest |

|---|

| 44% |

| 26% |

| 26% |

| 22% |

| 21% |

| 14% |

| 14% |

| 14% |

| 14% |

| 14% |

| 10% |

| 8% |

| 6% |

| 6% |

| 6% |

| 5% |

| 3% |

The highest discount rates were for early stage projects which could run out of money and are looking for the nonprofit equivalent of ‘venture capital.’

Giving sooner could be straightforward for people with existing savings, or the ability to borrow cheaply, for instance by expanding their mortgage.

If respondents are correctly estimating their discount rate, our results suggest that donors who are earning the market return on their savings (3-7%) or able to borrow at low interest rates could do more good by moving their donations to cash-poor organisations sooner rather than later.

The larger the gap between the organisation’s discount rate and the rate of investment returns, the greater the potential gains for the charity or donor by bringing forward donations.

Two downsides to be considered are that:

- Giving organisations very large reserves right away may make them less responsive to the views of donors, as they will not have to regularly show impressive results in order to continue attracting donations.

- If you borrow or draw down your savings, then you expose yourself to risk if your expected future income never materialises. This could occur if you get sick or lose your job. For this reason I would only recommend this strategy to people who will remain financially secure even after donating early.

What kinds of talent do we need more of?

People were asked both about what skills they wanted to see more in the community as a whole, and which skills they needed to attract for their own organisation. The results were widely dispersed:

| Skill | My org | EA as a whole | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good calibration, wide knowledge and ability to work out what's important | 20 | 21 | 41 |

| Generalist researchers | 20 | 13 | 33 |

| Management | 15 | 18 | 33 |

| Government and policy experts | 6 | 23 | 29 |

| Operations | 10 | 13 | 23 |

| Machine learning / AI technical expertise | 9 | 14 | 23 |

| Movement building, public speakers, public figures, public campaign leaders | 8 | 14 | 22 |

| Administrators / assistants / office managers | 10 | 6 | 16 |

| Biology or life sciences experts | 2 | 9 | 11 |

| Economists | 7 | 8 | 15 |

| Marketing & outreach (including content marketing) | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Other math, quant or stats experts | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| People extremely enthusiastic about effective altruism | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Communications, other than marketing and public figures | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Web development | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| People extremely enthusiastic about working on x-risk | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Developing world experts | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Software development | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Philosophers | 1 | 1 | 2 |

The most in-demand roles are researchers and managers, but we’d also like to highlight increasing demand for subject specialists, especially experts in policy, biology/life sciences, economics and mathemathics. Many people in the community think that these skill sets are needed to solve the highest-priority problems, but they’re also in short supply in the community.

We’d also like to highlight significant demand for people doing operations, administration and executive assistant work. These staff do things like create hiring processes, design office spaces to maximise productivity, and manage budget tracking processes. These roles are vital for running all of the organisations surveyed, but many are not able to hire as many good candidates for these roles as they would like. In particular, since this work is a little unglamorous, we think its value gets underappreciated, which makes these roles especially high-impact. We intend to write more about these roles in the future.

How to improve your judgement

The most requested skill-set was generalist research ability and great judgement about what’s true and what’s important. These are frustratingly vague descriptions though, similar to saying ‘we want really smart people’. Can we say a bit more about what EA organizations are after here?

One reason we think people request this skill set is that the community faces a great deal of uncertainty about questions in very ‘messy’ areas, where it’s hard to give a solid answer (e.g. which global problem is most pressing; what strategy the movement should take). This means that people who are able to do the following are extremely valuable: (i) synthesise many different types of information (ii) use that to create a practical recommendation (iii) which is well calibrated (i.e. neither over nor under-confident) and (iv) generated in a way that it can be explain to others so they can check it for themselves. A further reason to care about judgement is that it helps to avoid damaging errors in strategy or communications.

How can you cultivate these skills? One option might be to study a serious quantitative subject as an undergraduate or at grad school.

What if you’re not able to study now? We’ve compiled a list of ways to improve your rationality and decision-making.

More generally you will want to spend a lot of time talking to other people who think in a careful and reasonable way. Julia Galef has described this process of coming to use statistical reasoning in your everyday life like so:

“Bayes’ Rule is probably the best way to think about evidence. In other words, Bayes’ Rule is a formalization of how to change your mind when you learn new information about the world or have new experiences. … After you’ve been steeped in Bayes’ Rule for a little while, it starts to produce some fundamental changes to your thinking. For example, you become much more aware that your beliefs are grayscale, they’re not black and white. That you have levels of confidence in your beliefs about how the world works that are less than one hundred percent but greater than zero percent. And even more importantly, as you go through the world and encounter new ideas and new evidence, that level of confidence fluctuates as you encounter evidence for and against your beliefs.”

One approach for prompting this shift in thinking is to read the book Superforecasting by Philip Tetlock and then participate in prediction competitions like the Good Judgement Project Open Tournament. These will require you to think in gradations of certainty, compile conflicting pieces of evidence, and respond to feedback about your accuracy.

Which skills were less mentioned?

- People extremely enthusiastic about effective altruism

- Communications, other than marketing and public figures

- Web development

- People extremely enthusiastic about working on x-risk

- Developing world experts

- Software development

- Philosophers

Sorry to our many philosopher readers!

In most cases what’s driving the low scores is the preponderance of people with the skills on this list, though in some cases the organisations recently hired people in these categories (reducing the short-term need), and many of the organisations have recently deprioritized marketing.

However, the situation could easily change within a couple of years. Just last year, there was significant demand for web developers and engineers, and this demand could return equally quickly.

Moreover, if you have sufficiently high personal fit in one of these skill sets, it can still be a great option. For instance, the Global Priorities Institute is still hiring philosophers and philosophy is still one of the most frequent paths into global priorities research. We’ve also heard about some demand for freelance web developers.

How do the results compare to last time?

We changed the questions to make them more informative than last year’s survey, which makes direct comparison quite hard. However, the results seem in general quite similar.

The most likely shift is a higher willingness to pay for talented hires than a year ago.

Weaknesses of the survey

- The survey included 38 people from a range of organisations, but they did not all answer every question (see the presentation for sample sizes on each question). People without an organisation affiliation could not answer questions about e.g. their organisation’s willingness to pay for hires. The question with the fewest responses had 15 answers.

- For the org-size weighted means, some individuals’ answers could end up being very influential. This occurred if only one person from an organisation with a large budget answered a question. Each staff member from GiveWell could get a 10% sway over the weighted average, or 20% if only one answered. For this reason we report both the weighted and unweighted averages. Fortunately, in most cases they did not differ much.

- I expect many people answered difficult questions quite quickly without doing serious analysis. As a result the results will often represent a gut reaction rather than deeply considered views. As evidence of this, many people answered one of the trickier questions in reverse (giving 1/x rather than x). In other cases answers may reflect large amounts of thought over many years. We should update our views on these answers, but not treat them as the final word on the relevant questions.

- I tested the questions in an attempt to make them clear and unambiguous. However, some of them remain vague. For instance, one question asks about “If your quality-adjusted pool of applicants doubled for the next 3 years (vs staying constant)”. Different people may have interpreted this doubling quite differently.

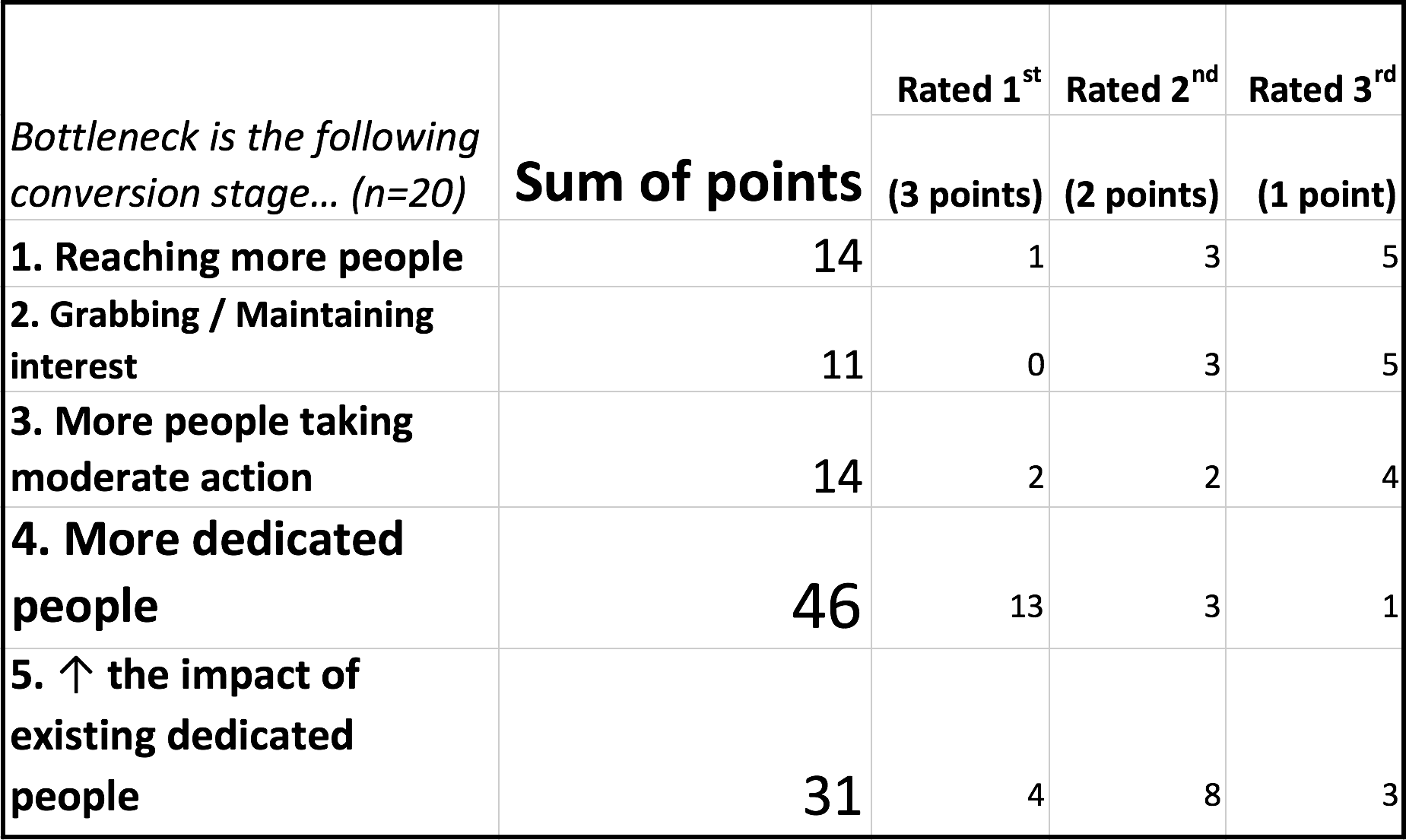

What’s the key bottleneck for the effective altruism community?

At the same event, we ran another survey (with a very similar methodology) asking what attendees believed is the key factor limiting the community’s ability to do more good. We broke stages of involvement down into five parts, which follow sequentially from each other, and asked where people thought the key bottleneck lay. The results are in the table below.

Note that each stage is a “conversion rate” from the previous stage. So if you answer stage (3), “more people taking moderate action”, it means that the key bottleneck is taking people from (2) to (3).

The key finding was that attendees believed the main bottleneck in the pipeline wasn’t reaching new people, but rather i) advancing people involved to the point where they’re taking the highest-impact opportunities, ii) and then helping those people accomplish more, with e.g. better training and access to information.

Because we agree with this view, 80,000 Hours has reoriented its material over the last year from the first 3 stages – which we previously felt were the bottleneck – towards the last two.

How diminishing are returns in the community?

We also asked about the rate of declining returns from extra funding across the community. We asked respondents to imagine that a well-informed donor in the community wins either a $1bn lottery, or a $100m lottery, and has to donate all of their winnings.

We then asked them to guess how many times more good they would do with $1bn rather than $100m. Across 20 respondents the median guess was 4.5, and the average was 5.1.

How fast will donations to meta-charities grow over time?

In summer 2016, we carried out another survey of 22 EA meta-charity donors who are earning to give, about their expected donations over time. The donors were all people who have donated to CEA/80k in the past, and who we thought might give over $50,000 per year (total) within the next five years. This group captures most of the large donors to other EA meta-charities, though will miss some. Over 90% of the people we asked responded, including all of the largest donors.

Here are the original aggregated results (updated results follow):

- Total donations per year, now: $5.6m

- Expected donations in five years: $16.3

- Annual growth rate: 23%

Across the sample, the donors gave a 75% chance of still being engaged in earning to give and donating in five years, which has already been taken into account in the expected donations figure.

Note that not all of these donors will donate everything to meta-charities. Rather, they expect to give to a range of EA areas, such as international development. The most popular alternative is direct efforts to mitigate existential risks. So, we’d guess that the amount available for meta-charities is about half of the total, or perhaps less.

In the year since the survey:

- Open Philanthropy project started funding EA meta-charities, in some cases covering up to 50% of their budgets, effectively doubling the total available funding.

- Two respondents have left earning to give and switched into direct work — we changed their expected donations in 5 years to zero.

- One large donor dramatically increased how much they intend to give.

This gives the following updated figures:

- Total donations per year, now: $11.1m

- Expected donations in five years: $38.7m

- Annual growth rate: 28%

Again, note that probably only around a half of these are available for meta-charities.

This is a significant amount of funding, but note that many of the organisations have grown their budgets at over 50% per year, and it seems likely this could be maintained. If this happens, then the funding available from existing donors will grow more slowly than the funding needed by the organisations.

This suggests the organisations could become funding constrained if they can’t find new donors in the next five years. In particular, there is a need to find donors who can “match” Open Philanthropy, which could provide much more funding, but generally doesn’t provide more than half of an organisation’s budget.

If the past track record of finding new donors continues, then this should be achievable with some effort.

Also note that the current donations are only just about enough to cover the large meta-charities that already exist. This suggests there may not be a large funding pool ready to go for new projects.

There are, of course, many reasons to be skeptical about these figures, and they should only be treated as highly approximate estimates. The donors might be biased upwards by excessive optimism about their future income or commitment to doing good. In the past however we have found people have underestimated their donations.

The estimate was significantly affected by 3 respondents, who each shifted that figure 4% or more. In a few cases the expected giving was based on highly volatile returns on startups the donors had founded.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to everyone who filled out the survey, and to Ben Todd and Peter McIntyre for help developing the survey.

Appendix 1 – How the talent survey was conducted and analysed

You can see exactly how the survey was taken here.

38 people filled out the survey, though not all people answered every question. 6 people who were asked to take the survey did not fill it out, yielding a response rate of 86%. Where necessary they were replaced with the next most senior person in their organisation. The following organisations had one or more respondents in the survey (usually senior staff):

- 80,000 Hours (3)

- AI Impacts (1)

- Animal Charity Evaluators (1)

- Center for Applied Rationality (2)

- Centre for Effective Altruism (3)

- Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (1)

- Charity Science: Health (1)

- DeepMind (1)

- Foundational Research Institute (2)

- Future of Humanity Institute (3)

- GiveWell (2)

- Global Priorities Institute (1)

- Leverage Research (1)

- Machine Intelligence Research Institute (2)

- Open Philanthropy (5)

- Rethink Charity (1)

- Sentience Institute (1)

- Unaffiliated (5)

The unaffiliated respondents were three EA researchers who are currently not working at EA organisations, and two major donors were also asked their opinions where relevant. DeepMind was a slightly odd inclusion, but the person working there recently left a job at another of these organisations, so we used their response.

Most people who filled it out requested that their answers be anonymised before being shared with anyone else. Unfortunately, for privacy reasons, we can’t share individual survey responses.

A median, mean, 10th percentile, and 90th percentile were calculated for each question’s results. For questions about organisations, a size-weighted mean was also calculated – i.e. if an organisation that made up 20% of the total budget of all the included organisations had two people fill out the survey, each of those would be given a 10% weight in this size-weighted average. If only one person answered a question from that organisation their answer would be given a 20% weighting.

The survey was checked for outliers that massively changed the answers, and only one was found. The answer was not an error, so an average with that answer excluded was also reported.

The survey on the biggest bottleneck and declining returns to extra donations was just a sample of 22 people present at the EA Leaders Forum 2017 who chose to fill out the survey (approximately 60% of attendees).

The survey on donors’ future giving expectations was conducted by personally contacting 22 donors who we knew to be planning to give substantial sums to effective altruist organisations.

Appendix 2 – Answers to open comment questions

(Totally optional) Any other comments on what we need more of in the community, or what characteristics or lack thereof most often hold people back from usefully contributing?

Operations (4)

“Applied skills, so being able to execute on projects. Taking action, so having a better thinking to doing ratio. ”

“Willingness to do whatever is most needed, extreme conscientiousness and attention to detail.”

“We need more general operations people, and people who would be excited to work in the same job >5 years (I’m worried we’re selecting too heavily for people with super steep growth trajectories, which are unreliable for building a org’s foundation).”

“Tendency to just keep volunteering and trying to find a way to make things go better/faster/more helpfully, without need of encouragement/permission.”

Communication and ability to welcome new members (2)

“People who, in addition to their enthusiasm about and deep familiarity with EA, also have the ability to see value in, and communicate with people doing relevant work. It can often be imposing for a newcomer to engage in the EA community; I would support taking steps to lower the entry point for the average person.”

“More concrete missions for newcomers/more efficient use of early enthusiasm”

Quality of thought (5)

“Really sharp people with good judgement”

“I’d guess we especially need people with “Good calibration, wide knowledge and ability to work out what’s important.” There’s so much stuff to look into and try to figure out, for EA cause prioritization/discovery and some other topics”

“The ability to be corrected and improved.”

“The other abilities that seem most important to me are reviewing evidence and coming to good conclusions, social skills, focusing on the object level, and creativity.”

“Ambitious experimentalists; people who enjoy rigorously examining unconventional ideas; people who prefer academia or industry over nonprofit work”

Different kinds of people (3)

“Ethnic and gender diversity.”

“I agree with the standard critique that we need to extend beyond the tech/macho culture and demographics so others, e.g. mainstream policy/activism leaders, feel more welcome.”

“I would love more older people with experience who are as flexible in their thinking and willing to update as most current talented EAs”

(Optional) Which problems beyond those already addressed by the four EA Funds above do you think are highest-priority for the community to research and work to solve?

Politics, collective decision-making and coordination (7)

Improving collective decision-making

Political cooperation

Global coordination

Politics

Mainstream values spreading, e.g. high-leverage anti-Trump work.

Improving public institutions, e.g. public discourse, etc, infrastructure, science

Political action and lobbying

Specific approaches to existential risk (3)

“…a separate fund focused on pathway changes that might affect the far future for the better: generally improving governmental/intergovernmental processes, thinking about the risks / benefits of fast vs slow technology improvement, how economic changes in the developing world might be expected to overall affect pathways.”

General x-risk research (figuring out what we’re missing)/global priorities research

Biosecurity

S-risks (3)

Reducing s-risk (in cooperative ways).

S-risk?

S-risks

Rationality (3)

Rationality

Improving epistemics

Individual and group rationality

Improving science research (2)

Improving science

Improving science? Pretty uncertain about this.

Other (4)

What institutions do we need to identify, sort, train, and efficiently incorporate new talent?

Basic research

Maybe mental health

Wild animal welfare

(Optional) Only answer this question if you answered 4 or 5 on the previous question: If you tried to spend more money on attracting talent what might you do? Would you raise salaries? Would there be negative side effects which stop you from doing whatever those things are (e.g. increasing costs for existing employees)?

“I think raising salaries 50% might boost hiring about 10% (e.g. it would make the difference for 1 in 10 candidates). Maybe existing staff would become 5-10% more productive, and more likely to stay. But we’d probably want to raise all salaries, so total costs would increase about 30%.”

“I don’t really know anything we could reasonably do with money to get more qualified people to join. They just don’t really exist.”

“We face institutional limits on how much we are able to pay. Also there is just simply a lack of people with the relevant skills.”

“Staff moves time from fundraising to recruiting. I’m pessimistic about standard approaches such as raising salaries or working with headhunters due to the extremely idiosyncratic requirements we have.”

“It is difficult to simply offer higher salaries; in that situation, your current staff would be unhappy unless you raised their salaries to meet the new standard. If you don’t raise their salaries then you risk losing them, and if you do raise those salaries then you risk increasing the burn rate of your organization in a significant way.”

“Raise salaries and invest in recruiting, since many good candidates likely aren’t aware of opportunities”

“Would like to be able to raise salaries, but have commitments that make this non-trivial. Would perhaps make efforts to create a particularly attractive work situation/role/give particular freedom or authority. Downsides include possibly fairness/bitterness among veteran employees.”

“The money would go to figuring out (and setting up the institutions to) identify, sort, and train the talent.”

“More training programs with proper salaries.”

“I’d endow chairs and fellowships.”

“I think the bottleneck is more about something like coming to trust and train people rather than a shortage of people who could eventually do the work.”

“I don’t think salaries has been a bottleneck to getting great people.”

“I’d consider providing bounties for referrals.”

“Could raise salaries, but then we would do it for existing employees which makes it more expensive – a bit reluctant to do that. Expect it would worsen the culture a bit. Could also offer better benefits or more flexibility in what people work on.”

“Raising salaries can cause fairness concerns if salaries of the rest of the team remain unchanged, can make us look worse to donors, and is unlikely to be very helpful for attracting top talent since the most suitable candidates are also the most altruistic ones. I’m not sure how we’d spend more money to attract talent. The main thing would be reducing senior staff time allocated to fundraising and increasing senior staff time allocated to hiring.”

“There are various things we might do, including raising salaries, hiring a recruiter, doing more outreach (e.g., establishing prize funds), and running more researcher trials in cases where we’re relatively uncertain about a researcher’s fit”

(Optional) Are there any ways in particular that CEA/80K could help you get the talent or funding you need?

“We would very much like to find an excellent, established career economist. Would guess that kind of person wouldn’t come through 80k though. Most likely, would like to meet people doing Philosophy/Econ PhDs at top schools, who seem extremely smart and EA-aligned.”

“get people to complete [relevant] PhDs ;)”

“We desperately need top-notch operations people.”

“We aren’t hiring much right now.”

“I often direct recent graduates to 80K. Increasing the amount of attention given to [cause of choice] would be helpful, but I understand that the same would be said by the leadership of other respective causes as well.”

“Connecting us with high-power marketing talent, or nudging such talent toward us—we’ve done our own search and came up dry because the quality we need carries a price tag we couldn’t hit (so finding the right person within the network of personally/intrinsically motivated EAs is high value).”

“Push more wannabe political/policy people my way, for coaching and/or direct assistance.”

“Probably. We’re trying to build [x] field, and that’s going to require pretty close coordination between orgs.”

“You could help by recommending donor prospects to us.”

“CEA could run test projects in research-writing/one-on-one/marketing/operations-assistant, and send us the best people. I’m not sure if this would be worth the cost for CEA, but I could see it being a decent boost to us.”

“Test more people so that others benefit from the information. Focus on growth with groups that have relevant skills.”

“Talk to me about what goes wrong and help me figure out who I need to hire.”

“Not much for our current hire, who will probably be someone we know due to the need for domain knowledge, but next year, when we’re more interested in just “bright young person with good writing skills and a strong interest in social change,” that seems like it could come from 80k’s pipeline.”

“Yes, finding good administrative, operations, and diplomatic staff”

“It would be great to collaborate more to improve funneling [x]-speaking EAs through 80K’s guide and advice, and putting them in touch with us if they’re good fits. There maybe further ideas, I’d have to think about it more.”

“Maybe build up organizations / events / side-communities that are more strictly oriented toward “discuss and collaborate on interesting unconventional questions in a really technically demanding way”.

If you’re still reading, you might be a good fit for a job at one of these organisations. Read more here and then get in touch.

Notes and references

- I wanted to check if projects in some cause areas got many more votes than others given the size of their budget. The four most overrepresented projects in terms of votes/budget were Sentience Institute, Global Priorities Institute, 80,000 Hours and Charity Science Health. The least represented were GiveWell, CSER, Animal Charity Evaluators and the Center for Applied Rationality. Overall while it was unfortunate to not get a broader sample, the submission for this question were spread across people working on a wide range of cause areas.↩