(Updated 5/11/23) School districts and charter organizations can request an extra 14 months to spend down the second round of federal Covid-relief aid, but must still obligate the money to a contract or project by the September 2023 deadline, according to the latest U.S. Department of Education guidance.

The guidance, issued May 5, sets the same rules for liquidating the federal funds that were put in place for the first round of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds last year, as well as to other funds authorized in the first two rounds of federal legislation.

School districts and charters must submit a request for an extension in spending to the state education agency, which then submits a request to federal officials. If granted the extension, they local agencies would have until January 2025 to use the ESSER II money. The new guidance does not address September 2024 deadline for spending the largest share of ESSER dollars, the $122 billion in the American Rescue Plan.

Only seven states and the District of Columbia applied for extensions in spending their ESSER I provided in the CARES Act, K-12 Dive has reported. All of those requests were approved, adding up to a delay in spending down about $6.6 million.

[Read More: Progress in Spending Federal Covid Aid: State by State]

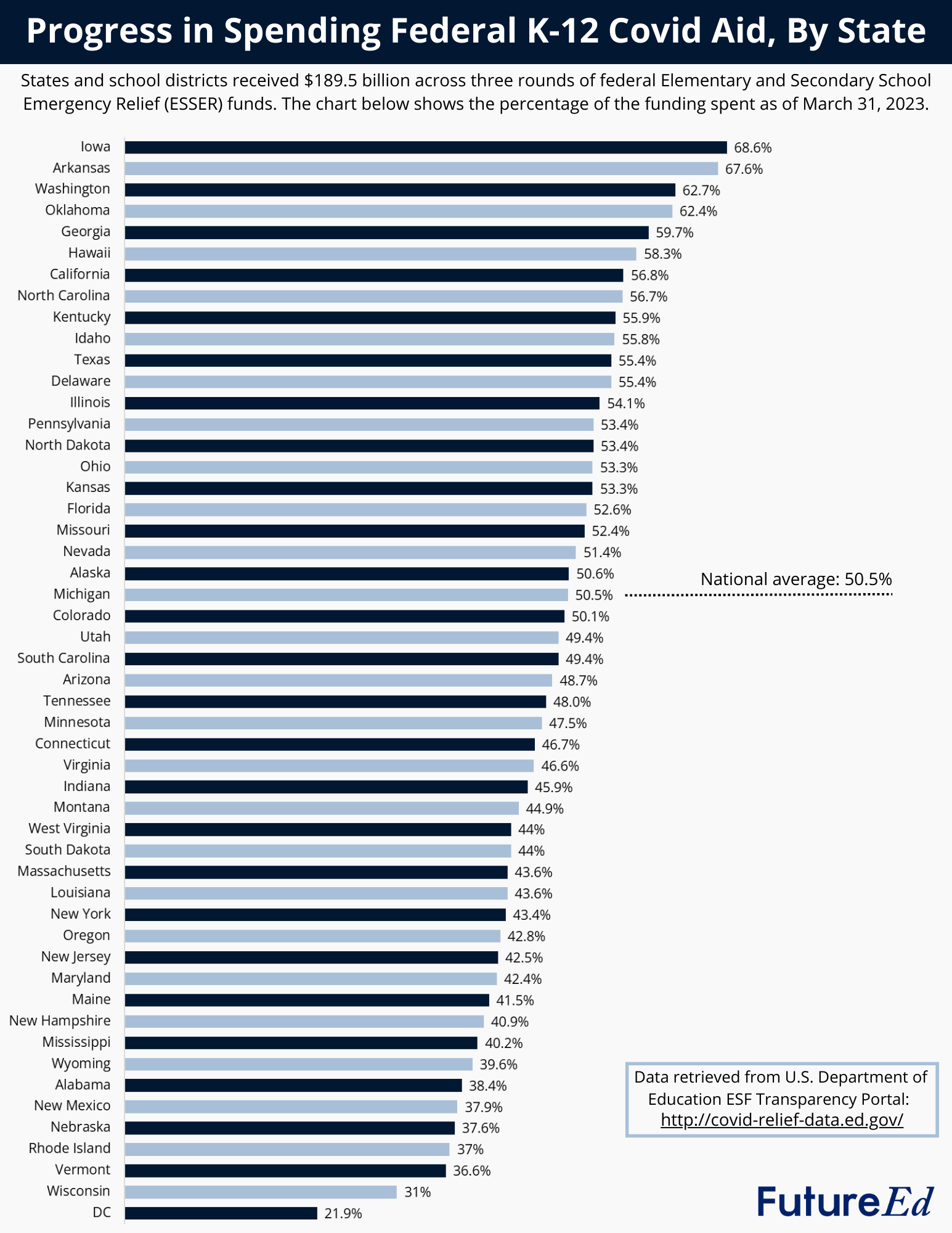

Overall, about 99 percent of the ESSER I funding has been spent and 74 percent of ESSER II, according to the latest federal data. For the third round of funding, states and districts have spent nearly 35 percent. FutureEd’s state-by-state breakdown of the data shows that spending is uneven. Schools in four states–Arkansas, Iowa, Oklahoma and Washington–has spent more than three fifths of their allotment, while Washington, D.C., has barely used one fifth.

Covid Spending in 2021

A federal analysis for fiscal year 2021, showed that states and districts spent about $14.2 billion in federal Covid-relief aid that year, with the bulk of the money going to address student academic and social needs and to pay personnel costs, according to a report from the U.S. Education Department.

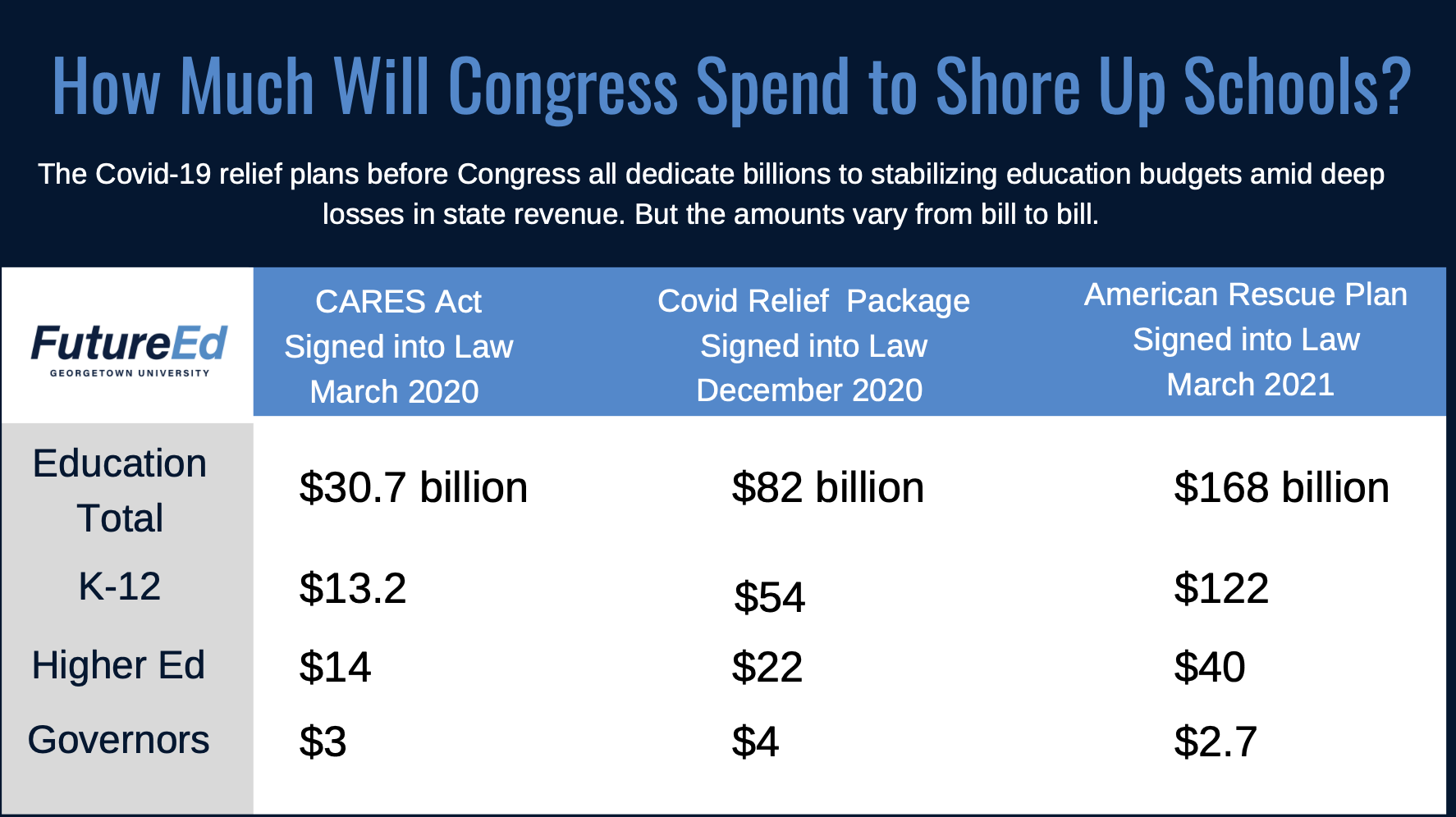

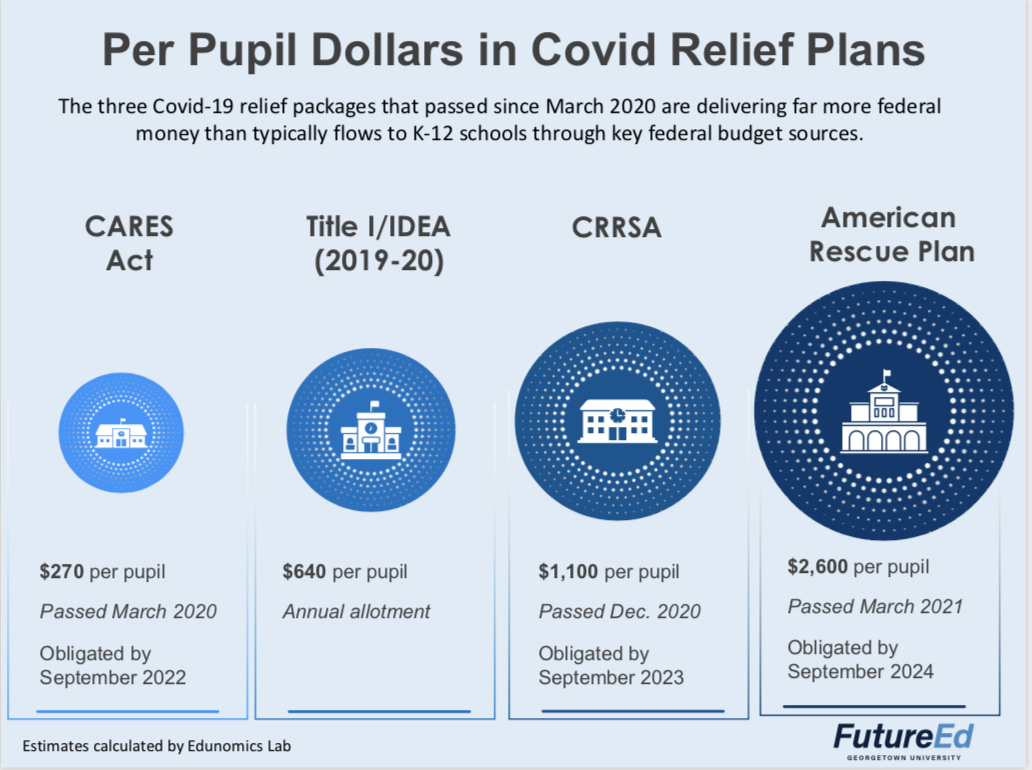

The report documents spending trends—and dollars earmarked—in the period from July 2020 to June 2021, the state fiscal year. By the end of that fiscal year, Congress has allocated nearly $189 billion for K-12 schools to spend in Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds. But the largest of those allotments, the American Rescue Plan, was approved in March 2021, and many local education agencies did not yet have access to the money or plans in place to spend it.

Nationally, about $6.1 billion or 43 percent of the money spent at the local level went to a category described as meeting student needs, the fiscal year 2021 analysis found. That includes spending on tutoring; summer and afterschool programs; rigorous curricula; additional school counselors, nurses, and school psychologists; and the implementation of community schools.

Broken down by accounting lines, personnel costs accounted for $6.2 billion or 44 percent of the spending. This overlaps somewhat with the spending on student needs as it includes hiring extra teachers, tutors and mental health professionals. It also encompasses providing bonuses for recruitment and retention and using federal funds to avoid layoffs.

[Read More: Financial Trends in Local School Covid-Aid Spending]

With many school districts reopening buildings during the 2020-21 school year, about $2.4 billion in ESSER funds went toward cleaning and equipping schools to prevent the spread of Covid, as well as upgrading school air quality and ventilation, the report found. A separate analysis by FutureEd shows that HVAC upgrades play a big role in plans for spending the third round of ESSER dollars, with at least half of districts earmarking money for such projects.

About 40 percent of school districts and charters also used the federal aid to give students greater access to the internet at home, with mobile hotspots being the most popular approach.

The 2021 report lags behind totals reported on the Education Department’s portal, which add up to about $67.5 billion as of September 30, 2022. Local and state education agencies have until September 2024 to obligate the remaining money

Education Spending in the Federal Budget

President Joe Biden is seeking a $10.8 billion increase in the U.S. Education Department’s budget in his 2024 spending plan, with extra money for preschool, high-needs schools, students with disabilities, and mental health support. The plan, released in March, would include $90 billion for education, the largest share of that–$20.5 billion–for Title 1 schools, which serve concentrations of students living in poverty.

The 2023 budget, approved, which Congress approved in December 2023, includes $79.6 billion for the education includes $18.4 billion in spending for schools serving students living in poverty–a 5 percent increase over last year’s budget but far short of the $36 billion President Joe Biden initially proposed for Title I spending.

The budget measure, which funds the federal government through most of 2023, also includes $28. 5 billion for school meal costs and provides more options for providing meals during the summer. It allots $15.5 billion for special education, $12 billion for Head Start and $8 billion for the Child Care and Development Block Grant. It did not include a tax credit that aimed at low-income families with children.

[Read More: 6 Ways to Breakdown How Districts are Spending Covid-Relief Aid]

About $2.2. billion will go toward career and technical education. Social-emotional learning programs will also receive a boost with $87 million set aside for innovation and research programs grants; $90 million to train teachers on SEL and “whole child” strategies; and $150 million–or double the amount from last year’s budget–to support full-service community schools.

At the higher education level, the omnibus bill before Congress provides more than $1 billion for institutions serving minority populations and would raise the maximum amount of money provided in a Pell Grant by $500 to $7,395.

The bill also calls on the U.S. Education Department to strengthen it support for the “timely and effective expenditure” of the nearly $190 billion in Covid-relief aid granted K-12 schools in three rounds of Congressional funding. The measure specifically students academic and mental health needs. And it calls for greater transparency in how the money is being spent at the local, state nd national level.

Guidance on Covid Spending

Earlier in December, the Education Department released expanded guidance on how school districts can spending billions in Covid-relief dollars in the next two years, but stopped short of providing any further extensions on the deadlines for spending later rounds of Congressional funding.

The 88-page document provides new and updated details on the rules for spending on construction projects, student mental health, chronic absenteeism, and other priorities that districts have identified as they spend down the unprecedented infusion of federal aid, most of it through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) fund.

The department provides expanded suggestions for how to use the money to stabilize the educator workforce, including increasing compensation, building teacher pipelines, recruiting substitutes and expanding support for educators’ well being. These funds can used in combination with other federal resources.

On the fraught issue of expanding timelines for spending the ESSER funds, the department agreed earlier this fall to allow districts extra time to spend the $13.2 billion that was approved in the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The money had to be obligated, committed to a contract, by September, but districts can continue using it for at least 18 months. In some instances, the new guidance states, spending can stretch longer in a multi-year contract.

[Read More: Getting to Yes on Covid Relief Spending]

A decision will come “at a later date” on extending deadlines for spending the $54 billion in ESSER funds allotted in the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSA) and the $122 billion in American Rescue Plan (ARP), the guidance states. In the meantime, the department encourages states and districts to spend “with urgency on activities that will support students’ academic recovery and mental health needs.”

Much of the new and updated material in the guidance relates to facilities projects. The department:

- Confirms that districts can use ESSER money for construction projects, but provides a series of requirements for such projects and repeats its cautions that facilities work may run up against the deadlines for spending the federal money.

- Clarifies that districts cannot use the federal money for athletic facilities–such as stadiums, playing fields and swimming pools–“unless there is a connection between the expenditure and preventing, preparing for, or responding to Covid.”

- Offers recommendations for state approval processes of district construction projects, including a checklist for local education agencies and provisions for historic preservation and protecting tribal lands. The projects do not require an environment impact assessment under federal law. If a state is pursuing capital projects with its share of the funding it must receive approval from the U.S. Department of Education.

- Provides detailed guidance and resources for districts renovating or replacing heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

- Allows the use of federal funds to keep schools open after floods, tornados and other natural disasters “in limited circumstances,” stressing that districts should rely primarily on FEMA funds.

- Allows for spending on gasoline and utilities when necessary to keep schools open and running.

- Provides details about how to dispose of equipment and supplies purchased with ESSER dollars but no longer needed.

- Allows the use of funds for purchasing and installing video security systems in limited circumstances “for promoting safe and secure schools.” But the department cautions districts to provide the necessary privacy protections and civil rights considerations.

In changes related to student academic and social-emotional needs, the guidance:

- Confirms that districts can include the costs of implementing an evidence-based practice in their calculation of spending 20 percent APR ESSER funds on academic recovery. These costs can include such things as professional development, cleaning the space where a program is held, snacks or meals for students staying late for an enrichment activity, or transportation.

- Allows the use of funding for art, theater and music classes “to help ensure equitable access to programs that meet students’ social, emotional, mental health, and academic needs.”

- Allows for providing food services or waive a student’s school meal balance, while recommending that districts tap other federal funding first.

- Provides additional guidance and resources on how to use ESSER funds for supporting student behavioral and mental health, as well as social-emotional learning.

- Provides detailed recommendations for using federal Covid aid to support multi-lingual learners, including assessing their progress and engaging with families.

- Provides detailed recommendation for using funds to reduce chronic absenteeism, including outreach to students and families; accelerating learning for students; and other intensive social, emotional, mental health, and academic supports. The guidance, however, specifically prohibits paying students and families directly for school attendance.

- Provides guidance for developing and implementing early warning indicator (EWI) systems, which can track attendance, assignment or course completion and credit accumulation, grades, and discipline rates.

- Confirms that a district cannot provide ESSER funds to another organization through a sub grant.

Extending CARES Act Dollars

Earlier this fall, the department outlined the following process for obtaining extensions for the CARES Act dollars, which had to be obligated by September 30. The department’s spending portal shows that most of the $13.2 billion had been obligated by that date, but there are concerns that some contracts may need more time.

.[Read More: How Local Educators Plan to Spend Billions in Federal Covid Relief Aid]

This is particularly true for construction and facilities work, which has been slowed down by labor and supply shortages. About half of school districts and charter schools are planning to invest some of the Covid-relief money in upgrades to HVAC systems, and a third are spending on repairs to prevent illness, a category that includes lead abatement and mold removal, according to a FutureEd analysis of spending plans for more than 5,000 districts and charters compiled by the data-services firm Burbio.

The process for requesting a CARES Act extension includes:

- Local districts and charter organizations submit extension requests to their state education agencies for spending that is obligated but not yet expended. The extensions apply to contracts that school districts have committed to, not salaries for school staff.

- States can request “any additional information and documentation they deem necessary to support the liquidation extension request and ensure proper oversight.”

- The states submit the request to the U.S. Education Department by December 31, 2022.

- States must agree to “continue to conduct oversight of the [local agencies], attest to the allowability of the expenses to be liquidated, maintain documentation to support the expenditures’ timely obligation, and attest that included subgrantees are low-risk entities.”

Neither that memo nor the Dec. 7 document offers extensions for the CRRSA aid, which must be committed by September 2023, or ARP funds, which must be obligated by September 2024.

Education Budget: 2022

In early 2022, Congress approved a spending plan that provided $42.6 billion for K-12 schools for the remainder of the fiscal year, an increase of $2 billion from the past year with extra funding for schools serving students living in poverty, for mental health services and Community Schools programs. the omnibus plan was far less ambitious than the budget proposed by President Joe Biden and approved by the House in fall 2021.

The largest share of the K-12 money in that measure, $17.5 billion, went to the Title I program serving disadvantaged students. That’s a $1 billion increase over the past year, compared to the $20 billion increase that Biden initially proposed. Another $13.3 billion went toward grants to support services for students with disabilities, which is more than the fiscal year 2021 budget but lower than the funding level provided during the pandemic. About $2.2 billion was to pay for educator professional development and support, and $1.2 billion for grants supporting school safety and student health.

Support for student mental health, which Biden stressed in his State of the Union address, received a boost with:

- $111 million budgeted for mental health professionals in schools, up from $16 million last year

- $55 million toward related demonstration grants, up from $10 million last year

- $56 million for support school-based mental health services grants, up from $11 million last year

- $82 million for social-emotional learning, up $15 million from last year

- $75 million for full-service Community Schools, up from $30 million in fiscal year 2021 but far below the $443 million sum Biden originally requested

- $120 million for Project AWARE, an increase of $13 million over last year in the Health and Human Services budget

The proposal did not include an extension of a waiver allowing schools to continue serving free meals to all students, but did provide $26.9 billion for child nutrition in the Department of Agriculture budget.

Overall, the Department of Education was to receive $76.4 billion for K-12 and higher education, out of the $1.5 trillion package aimed at keeping the government running and providing additional support for Ukraine. In fall 2021, Biden signed into law a $1.2 trillion infrastructure package that provides money for schools to remove lead pipe lines, expand broadband access and purchase electric school buses.

Covid Relief Funding

Congress has allotted nearly $190 billion in Covid-relief aid to public schools through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER). The U.S. Education Department has approved all 51 state plans submitted for spending the federal money, and districts have developed plans and begun spending their share of funding provided in the American Rescue Plan (ARP).

To help guide spending, the department released a frequently-asked-questions sheet laying out the rules for states to review local plans for spending the ARP money and other relief aid that will flow to school districts. It makes clear that state legislatures or departments of education cannot limit how localities use the money, as long as the uses are within the bounds of the federal law. And states and localities cannot use the relief aid to replenish “rainy day” funds. Further guidance clarified how districts can use the funding for transportation, including to address the school bus driver shortage that many places are facing.

[Read More: Financial Trends in Local Covid-Relief Spending]

The department’s guidance also reiterates the need for states and local districts to use “evidence-based” interventions to help students recover from lost instructional time during the pandemic and clarified that the definitions of evidence-based match those provided in the Every Student Succeeds Act. “Given the novel context created by the COVID-19 pandemic, an activity need not have generated such evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic to be considered evidence-based,” the guidance explains. A Education Department website features best practices for using the relief aid to reopen schools safely and support the academic and social emotional needs of students.

[Read More: How States Are Using Federal Funds for Learning Recovery]

The guidance document makes clear that schools can use the federal dollars to pay for health-related expenditures needed to reopen safely–including vaccinations and testing for students and staff members–as well as for any community outreach needed to persuade students and families that it’s safe to return to school.

School construction is an allowable use for Covid relief funds–including new projects, renovations to ventilation systems, and purchasing trailers. But the guidance cautions against large capital projects that will require too much money and entail not only approval from the state but complex requirements for using federal money for such purposes. “Remodeling, renovation, and new construction are often time-consuming, which may not be workable under the shorter timelines,” for the relief aid, which must be obligated by September 2024.

The money can be used to support nontraditional students, include 2020 graduates who have yet to connect to jobs or postsecondary opportunities and adult students, including English language learners.

In April 2021, the department released an interim rule laying out a process for states to develop and submit plans for spending their share of the $122 billion the American Rescue Plan reserved for public K-12 schools. The department also provided a template for state plans.

[Read More: Parsing the Evidence Requirement of Federal Covid Aid]

Local school districts and charter networks were required to develop spending plans and submit them to their state education agency. Like the state plans, these proposals included information on mitigation strategies for safe reopening, evidence-based interventions, other spending plans, and an explanation of how the spending will address the needs of disadvantaged students. Local districts were required to seek input from the broader community and review their plans every six months for possible revisions.

Also, the Education Department released complex guidance for how districts and states can navigate the so-called “maintenance of effort” clause designed to ensure that the federal cash will be used to expand educational opportunities, rather than just replace the state and local dollars that now support schools. The clause appears in all three Covid relief packages, and the guidance sorts outs differences among the pieces of legislation. It also offers rules for seeking waivers from this requirement.

[Read More: Education Department Perspectives on Covid Relief Spending]

Recognizing the differences in how state calculate school finance, the guidance offers overall principles for evaluating the maintenance of effort. States that do not meet the requirements could lose out on future dollars or have to return existing funds.

In addition, the department released guidance explaining how states and school districts can meet the requirements for using federal Covid relief money in ways that provide equitable support to schools dealing with concentrated poverty.

American Rescue Plan

The American Rescue Plan includes:

- $122 billion for K-12 schools to be distributed through the federal Title I formula for funding schools and districts with concentrated poverty. The K-12 dollars will be focused on helping schools reopen and helping students catch up on learning they have missed during the pandemic. Districts must spend at least 20 percent of the money addressing learning loss and must make public a plan for returning to in-person schooling safely. Another $2.75 billion is allotted for private K-12 schools, bringing the total to about $125 billion.

- State education agencies can hold on to about 10 percent of the allocation before distributing the remainder to districts. State agencies must spend at least 5 percent on learning loss, 1 percent on summer learning, and 1 percent on afterschool programs.

- $40 billion to support higher education institutions, most of which would go in direct grants to public and nonprofit colleges and universities, as well as vocational programs. Minority serving institutions would receive additional support.

- $2.75 billion for governors to share with private schools. This is the primary mechanism for supporting schools beyond the public sector.

- $7.2 billion for the E-rate program that makes it easier to connect homes and libraries to the internet.

- $3 billion in added funding to support students with disabilities

- $1 billion to expand national service programs to support response and recovery, including tutoring programs in schools and other priorities.

- $800 million to support education and wraparound services for homeless children, all of which has been released to states.

In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will give states $10 billion for COVID-19 screening testing for K-12 teachers, staff, and students in schools.

Congress pursued approval of Biden’s package through a process known as budget reconciliation, which can be achieved with a simple majority of votes. Biden, who called for bipartisan support for the measure, met in early February with 10 Republican senators arguing for their own scaled-down, $618 billion plan. Biden declined to accept the package, and no Republicans voted for the final version of the measure in either house.

[Read More: Why Investing in Ventilation Could Pay Dividends for Learning]

Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act

The December 2020 package, known as the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSA) provides:

- $54.3 billion for K-12 schools, largely delivered through Title I funding. That’s about four times what schools received in the CARES Act approved in March.

- $22.7 billion for higher education with $1.7 billion set aside for minority-serving institutions and close to $1 billion for for-profit colleges

- $4 billion for governors to spend at their discretion, with $2.7 billion of that for private schools

The U.S. Education Department released a breakdown of how much relief aid each state would receive for K-12 schools, as well as discretionary dollars for governors. The governors fund represents the primary mechanism for providing relief aid to private K-12 schools.

CRRSA also includes $7 billion to expand broadband access, $10 billion for child care, and continued funding for school meal programs. And it includes $2 billion for motor bus operators, some of which can be used for school buses. Separately, lawmakers agreed to lift a ban on Pell Grants for prison education programs, an agreement included in the bill funding the government through the fiscal year. The higher ed agreement would also simplify the FAFSA form required for applying for federal financial aid, expand Pell Grants support to 500,000 new low-income college students, and cancel $1 billion in debt at historically Black colleges and universities.

The December Covid relief deal was far smaller than the $2.2 trillion Democratic leaders had been seeking for much of the Fall but higher than the $500 billion that Senate Republicans favored. The measure left some education leaders disappointed. American Council of Education President Ted Mitchell released a statement calling the funding for higher education “wholly inadequate.” Alliance for Excellent Education President and CEO Deborah S. Delisle praised the overall effort but faulted Congressional leaders for failing to include $3 billion for the E-Rate program, money that had appeared in previous relief proposals. School choice advocates found little of the support for private schools contained in Republican-backed bills.

Uses For K-12 Dollars

The bulk of the money allotted to stabilize K-12 schools goes directly to school districts based on the proportion of funding they receive through Title I of the federal Every Student Succeeds Act.

The Congressional measures allow for a broad range of uses for dollars to stabilize schools. Districts can essentially use it for any activity allowed under other federal laws for education, including those for students with disabilities and those who are homeless. These include:

- Improving coordination among state, local, tribal and other entities to slow the spread of Covid-1

- Providing resources that principals need to address coronavirus at their schools

- Supporting school district efforts to improve preparedness

- Addressing learning loss especially among disadvantaged students, including those living in poverty, learning English, experiencing homelessness, dealing with disabilities or living in foster care

- Training staff on the best ways to sanitize schools and proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE)

- Purchasing PPE and the supplies needed to clean and disinfect schools. The CDC has provided an analysis of the costs of such resources.

- Planning for school closures

- Purchasing the hardware and software needed to conduct remote and hybrid learning

- Providing services to support student mental health

- Supporting afterschool and summer learning programs

- Using evidence-based approaches to address learning loss, which can include assessments and distance learning equipment

- Repairing school facilities, especially ventilation systems, to improve air quality and reduce spread of Covid

At least 20 percent of the money provided in the American Rescue Plan must be spent to address lost learning. The law specially mentions the need to administer high quality assessments to determine academic needs, implement evidence-based practices, support students and families in distance learning, track student attendance and engagement during remote instruction, and monitor student academic progress to identify students who need more help.

Under CRRSA, governors will divvy up about $4 billion in aid, $1.3 billion of that for public schools and for higher education institutions most significantly impacted by the pandemic. Another $2.75 billion can go to private and parochial K-12 schools for such things as equipment, training, staff and other expenses needed to keep schools running. The measure specifically prohibits using the new money to support private school vouchers or other mechanisms for spending public money on private school tuition. The only exception is for governors who used their first round of discretionary dollars for such purposes. The only money allotted to governors in the March stimulus package is a $2.75 billion fund for private schools.

State-by-State Breakdown for K-12 Funding

Here are U.S. Education Department estimates of the amount of money that state and local school districts should receive under December’s CCRSA measure, and the American Rescue Plan (ARP).

| CRRSA | ARP | ||||||

Total |

Local Share |

State Share |

Total |

Local Share |

State Share |

||

| NATIONAL | 54.3B | 48.8B | 5.4B | 121.9B | 109.7B | 12.1B | |

| ALABAMA | 899M | 809.5M | 89.9M | 2B | 1.8B | 202M | |

| ALASKA | 159.7M | 143.7M | 15.9M | 358.7M | 322.8M | 35.8M | |

| ARIZONA | 1.1B | 1B | 114.9M | 2.6B | 2.3B | 258.2M | |

| ARKANSAS | 558M | 502.2M | 55.8M | 1.2B | 1.1B | 125M | |

| CALIFORNIA | 6.7B | 6B | 670.9M | 15B | 13.5B | 1.5B | |

| COLORADO | 519.3M | 467.3M | 51.9M | 1.1B | 1B | 116M | |

| CONNECTICUT | 492.4M | 443.1M | 49.2M | 1.1B | 995.3M | 110.5M | |

| DELAWARE | 182.8M | 164.6M | 18.2M | 410.7M | 369.7M | 41M | |

| D.C. | 172M | 154.8M | 17.2M | 386.3M | 347.6M | 38.6M | |

| FLORIDA | 3.1B | 2.8B | 313.3M | 7B | 6.3B | 703.8M | |

| GEORGIA | 1.9B | 1.7B | 189.2M | 4.2B | 3.8B | 424M | |

| HAWAII | 183.5M | 165.2M | 18.3M | 412.3M | 371M | 41.2M | |

| IDAHO | 195.8M | 176.3M | 19.5M | 439.9M | 395.9M | 43.9M | |

| ILLINOIS | 2.2B | 2B | 225M | 5B | 4.5B | 505.4M | |

| INDIANA | 888M | 799M | 88.8M | 1.9B | 1.7M | 199.4M | |

| IOWA | 344.8M | 310.3M | 34.4M | 774.5M | 697M | 77.4M | |

| KANSAS | 369.8M | 332.8M | 36.9M | 830.5M | 747.7M | 83M | |

| KENTUCKY | 928.2M | 835.4M | 92.8.M | 2B | 1.8B | 208.4M | |

| LOUISIANA | 1.1B | 1B | 116M | 2.6B | 2.3B | 260.5M | |

| MAINE | 183.1M | 164.8M | 18.3M | 411.3M | 370.1M | 41.1M | |

| MARYLAND | 868.7M | 781.8M | 86.8M | 1.9B | 1.7B | 195.1M | |

| MASSACHUSETTS | 818.4M | 733.4M | 81.4M | 1.8B | 1.6B | 183M | |

| MICHIGAN | 1.6B | 1.5B | 165.6M | 3.7B | 3.3B | 371.9M | |

| MINNESOTA | 588M | 529.3M | 58.8M | 1.3B | 1.1B | 132M | |

| MISSISSIPPI | 724.5M | 652M | 72.4M | 1.6B | 1.4B | 162.7M | |

| MISSOURI | 871.1M | 784M | 87.1M | 1.9B | 1.7B | 195.6M | |

| MONTANA | 170M | 153M | 17M | 382M | 343.8M | 38.2M | |

| NEBRASKA | 243M | 218.M | 17M | 545.9M | 491.3M | 54.5M | |

| NEVADA | 477.3M | 429.6M | 47.7M | 1B | 964.7M | 107.1M | |

| NEW HAMPSHIRE | 156M | 140.4M | 15.6M | 350.5M | 315.4M | 35M | |

| NEW JERSEY | 1.2B | 1.1B | 123M | 2.7B | 2.4B | 276.4M | |

| NEW MEXICO | 435.9M | 392.3M | 43.5M | 979M | 881.1M | 97.9M | |

| NEW YORK | 4B | 3.6B | 400.2M | 8.9B | 8B | 898.8M | |

| NORTH CAROLINA | 1.6B | 1.4B | 160.2M | 3.6B | 3.2B | 360M | |

| NORTH DAKOTA | 135.9M | 122.3M | 13.5M | 305.2M | 274.7M | 30.5M | |

| OHIO | 1.9B | 1.8B | 199.1M | 4.4B | 4B | 447.2M | |

| OKLAHOMA | 665M | 598M | 66.5M | 1.5B | 1.3B | 149.3M | |

| OREGON | 499.1M | 449.2M | 49.9M | 1.1B | 1B | 112.1M | |

| PENNSYLVANIA | 2.2B | 2B | 222.5M | 4.9B | 4.5B | 499.6M | |

| RHODE ISLAND | 184.8M | 166.3M | 18.4M | 415M | 373.5M | 41.5M | |

| SOUTH CAROLINA | 940.4M | 846.3M | 94M | 2.1B | 1.9M | 211.2M | |

| SOUTH DAKOTA | 170M | 153M | 17M | 382M | 343.8M | 38.2M | |

| TENNESSEE | 1.1B | 996.8M | 110.7M | 2.4B | 2.2B | 248.7M | |

| TEXAS | 5.5B | 4.9B | 552.9M | 12.4B | 11.1B | 1.2B | |

| UTAH | 274M | 246.6M | 27.4M | 615.5M | 553.9M | 61.5M | |

| VERMONT | 126.9M | 114.2M | 12.7M | 285.1M | 256.6M | 28.5M | |

| VIRGINIA | 939.2M | 845.3M | 93.9M | 2.1B | 1.9B | 210.9M | |

| WASHINGTON | 824.8M | 742.3M | 82.4M | 1.8B | 1.6B | 185.2M | |

| WEST VIRGINIA | 339M | 305.1M | 33.9M | 761.4M | 685.2M | 76.1M | |

| WISCONSIN | 686M | 617.4M | 68.6M | 1.5B | 1.3B | 154M | |

| WYOMING | 135.2M | 121.7M | 13.5M | 303.7M | 273.3M | 30.3M |

The CARES Act

The first round of Congressional relief aid directly for K-12 schools came in the $2 trillion March 2020 stimulus package, known as the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act, which $13.2 billion for K-12 schools, although several other bills were considered.

The stimulus bill earmarked $30.7 billion under an Education Stabilization Fund for states to spend on education, including $13.2 billion for the Elementary and Secondary School Education Relief Fund and $14 billion for Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund. Another $3 billion went to the Governors Emergency Education Relief Fund, which governors can use for “significantly impacted” school districts or higher education institutions.

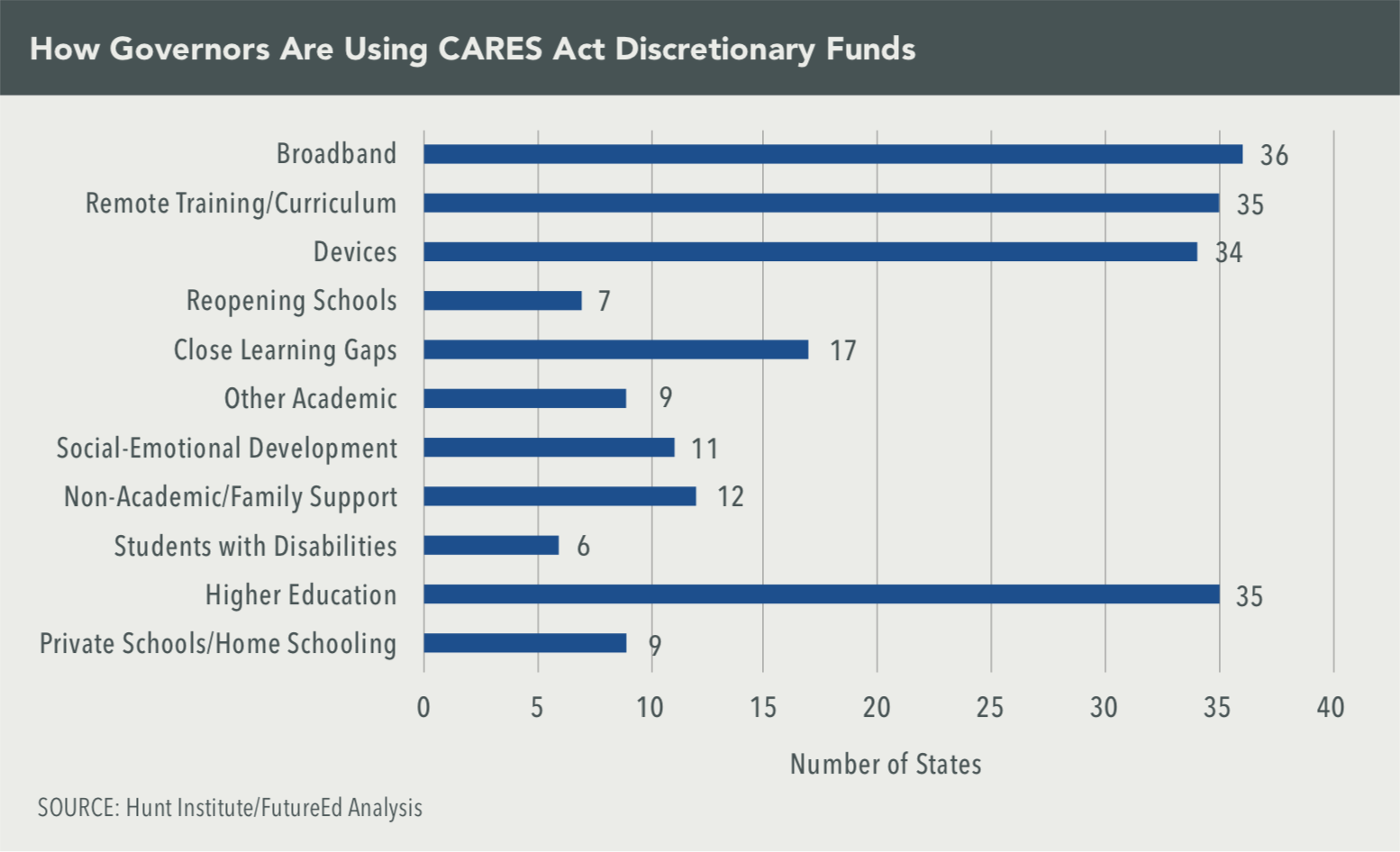

[Read More: How Governors Are Spending Their CARES Act Education Dollars]

The U.S. Education Department released estimates of how much money each state should receive, ranging from $32 million in stabilization funding for K-12 education in Wyoming to $1.6 billion in California. (see full chart below) Under the governors discretionary funding, New York will have $164 million to spend, while Rhode Island will have less than $9 million. In California, EdSource has calculated how much each of the state’s school district could receive. The CARES Act money must be obligated by September 2022. The department released a frequently asked questions sheet about the process.

The law list 12 allowable uses of the $13.2 billion in the package’s K-12 relief fund:

- Any activity authorized by the ESEA of 1965, including the Native Hawaiian Education Act and the Alaska Native Educational Equity, Support, and Assistance Act, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the Adult Education and Family Literacy Act, the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006, or subtitle B of title VII of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act.

- Coordination of preparedness and response efforts of local educational agencies with state, local, Tribal, and territorial public health departments, and other relevant agencies, to improve coordinated responses among such entities to prevent, prepare for, and respond to coronavirus.

- Providing principals and others school leaders with the resources necessary to address the needs of their individual schools.

- Activities to address the unique needs of low-income children or students, children with disabilities, English learners, racial and ethnic minorities, students experiencing homelessness, and foster care youth, including how outreach and service delivery will meet the needs of each population.

- Developing and implementing procedures and systems to improve the preparedness and response efforts of local educational agencies.

- Training and professional development for staff of the local educational agency on sanitation and minimizing the spread of infectious diseases.

- Purchasing supplies to sanitize and clean the facilities of a local educational agency, including buildings operated by such agency.

- Planning for and coordinating during long-term closures, including for how to provide meals to eligible students, how to provide technology for online learning to all students, how to provide guidance for carrying out requirements under IDEA and how to ensure other educational services can continue to be provided consistent with all Federal, State, and local requirements.

- Purchasing educational technology (including hardware, software, and connectivity) for students who are served by the local educational agency that aids in regular and substantive educational interaction between students and their classroom instructors, including low-income students and students with disabilities, which may include assistive technology or adaptive equipment.

- Providing mental health services and supports.

- Planning and implementing activities related to summer learning and supplemental afterschool programs, including providing classroom instruction or online learning during the summer months and addressing the needs of low-income students, students with disabilities, English learners, migrant students, students experiencing homelessness, and children in foster care.

- Other activities that are necessary to maintain the operation of and continuity of services in local educational agencies and continuing to employ existing staff of the local educational agency.

The CARES Act includes an additional $100 million in grants under Project SERV, which is dedicated to helping school districts and post-secondary institutions recover from “a violent or traumatic event that disrupts learning.” That pot of money can support distance learning, as well as mental health counseling and disinfecting schools.

Microgrants and Private Schools

In addition, then Education Secretary Betsy DeVos launched a $180 million “Rethink K-12 School Models” competitive grant program, designed to focus on helping states and families with virtual learning and the needed technology particularly during the Covid emergency. She encouraged states to develop innovative models “not yet imagined” for providing remote education. Congressional critics slammed the grant program as a backdoor approach to providing vouchers to parents who want to educate their children at home or in private institutions.

DeVos acknowledged as much in a May 2020 interview on SirusXM radio, saying the funding could allow parents to send their children to faith-based schools. “For more than three decades that has been something that I’ve been passionate about. This whole pandemic has brought into clear focus that everyone has been impacted, and we shouldn’t be thinking about students that are in public schools versus private schools.”

In July 2020, Devos awarded $180 million in grants to 11 states to support virtual coursework, training for remote instruction, and electronic devices. DeVos announced grants ranging from $6 million to $20 million to 11 states: Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, North Carolina, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas. Several states, including Rhode Island and Texas will enhance their virtual coursework offerings, which could benefit students from shuttered schools as well as homeschoolers. New York will put the bulk of its money toward training teachers in remote instruction, while Louisiana sets aside some of its grant providing devices and internet hotspots for 12,000 students. South Carolina is exploring a way to deliver remote instruction without internet access.

[Read More: The Challenge of Taking Attendance in Remote Learning]

Private school funding was also a point of contention after the Education Department developed guidance and then an interim rule explaining how CARES Act dollars should be shared with private schools. Typically Title I dollars can flow to private school students for “equitable services,” such as tutoring, if the students are deemed low achieving and live in an attendance zone for a Title 1 public school. The initial guidance called for school districts to provide these services, including materials and equipment, to any students and teachers in non-public schools, regardless of whether the students are low-achieving or live in the right attendance zones. The share for private schools would have to be proportionate to the share of all students in the district attending such schools. The interim released in July gave school districts more flexibility, but ultimately directed more federal dollars to private institutions.

In addition, at least four governors have devoted some of CARES Act discretionary funds to tax-credit scholarships for private schools, and other allow private schools to compete for grants.

In addition, at least four governors have devoted some of CARES Act discretionary funds to tax-credit scholarships for private schools, and other allow private schools to compete for grants.

In August 2020, a federal judge in Washington state put a temporary hold on DeVos’s rule, agreeing with state officials that sharing more federal aid with private schools could cause “irreparable harm” to public schools. “The Department’s claim that the State faces only an economic injury, which ordinarily does not qualify as irreparable harm, is remarkably callous, and blind to the realities of this extraordinary pandemic and the very purpose of the CARES Act: to provide emergency relief where it is most needed,” Judge Barbara Rothstein wrote in her opinion.

Later that month, a federal judge in the Northern District of California issued a similar ruling blocking implementation in a lawsuit filed by Michigan, California, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin; the District of Columbia; an school districts in New York City, Chicago, Cleveland and San Francisco. “The Department may prefer to give CARES Act funds to private schools more generously than Congress provided, but it is Congress who makes the law, and an ‘agency has no power to ‘tailor’ legislation to bureaucratic policy goals by rewriting unambiguous statutory terms,’” U.S. District Judge James Donato Donato wrote in issuing his temporary injunction.

And in September, a federal judge in Washington, D.C. issued a summary judgment effectively invalidating DeVos’s interim rule nationwide. U.S. District Judge Dabney Friedrich ruled that the education secretary overstepped her authority and misinterpreted what Congress intended for the CARES Act funding.

“In enacting the education funding provisions of the CARES Act, Congress spoke with a clear voice…,” wrote Friedrich, a Trump appointee to the court. “Contrary to the Department’s interim final rule, that cannot mean the opposite of what it says.”

Other 2020 Legislation

For months in 2020, negotiations in Congress snagged over a provision that would protect companies and other entities from liability in coronavirus-related lawsuits, something that Democrats opposed. Republicans, meanwhile, objected to money going to state and local governments, concerned that the federal dollars would simply pay off past debt or go to pension funds.

The House approved the $3 billion HEROES Act in May and a scaled down version in October, which includes $175 billion for stabilizing K-12 schools, $27 billion for higher education, $2 billion for Bureau of Indian Education-funded schools and Tribal Colleges and Universities, and $4 billion for governors to split. Another $5 billion in grants would have gone toward improving K-12 facilities, including school ventilation systems. And $11.9 billion was intended to help colleges and universities address pandemic-related challenges. That bill garnered no support from GOP House members, and despite White House negotiations, Senate Republicans said they had little interest in a deal larger than $1 trillion.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell focused instead on a smaller “highly targeted” $500 billion package, which failed to muster the needed votes on Sept. 10 and again on Oct. 21. That measure would have provided about $100 billion for education, with two thirds of K-12 aid reserved for schools and districts with in-person classes. The December measure has no such restrictions. The Republican package would also have supported private schools with proposals for a two-year pandemic tax credit program to pay tuition scholarships, extra dollars to expand state tax credit voucher programs, and permission for parents to use 529 savings accounts to pay for homeschooling costs. None of these provisions were included in the final package approved in December.

[Read More: How the Federal Government Can Help School Reopen Safely]

Beyond Capitol Hill, courts have weighed in on coronavirus relief by blocking a a controversial Education Department rule requiring public school districts to share more of the federal Covid aid with private schools. On Sept. 4, U.S. District Judge Dabney Friedrich in Washington, D.C., ruled that then-Education Secretary Betsy DeVos misinterpreted Congress’s intent when she drafted an interim rule for how CARES Act dollars should be spent.

Students with Disabilities

The American Rescue Plan dedicates $3 billion toward funding the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Beyond the new money allotted, The Education Department has been offering states more flexibility in how they spend their existing money, with release of a template for requesting waivers. This could allow schools to spend more of the federal dollars on technology for distance learning.

While the CARES Act gives the DeVos broad authority for waiving accountability requirements, lawmakers stopped short of allowing waivers for special education rules and gave DeVos a month to report her recommendations to Congress. In an April 2020 report, she did not recommend any waivers for the “core tenets” of the federal law that requires providing services for students with disabilities. She did suggest flexibility on time lines for evaluation to ensure that toddlers with disabilities don’t lose the support they need.

Schools are grappling with how to deliver services—such as physical or occupational therapy—or meet timelines set in individualized education plans (IEPs) required under federal law. Or even how to get the required signatures for IEPs. Some districts initially declined to provide instruction to any students because they could not address the needs of those with disabilities. The U.S. Education Department discouraged that sort of thinking.

Child Nutrition

Another important aspect of student health is nutrition. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, approved in mid-March, provides greater flexibility for schools to serve free meals beyond the school grounds. Some schools are allowing families to pick up food at community centers or using school buses to deliver meals. The measure also allows student who qualify for free and reduced-price meals to receive benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The U.S. Agriculture Department has granted districts considerable flexibility and extended those waivers through June 2022. In addition:

- The American Rescue Plan includes more than $5 billion to extend the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program throughout the school year and summer, giving students uninterrupted access to meals during the pandemic.

- The December relief package included $13 billion for increased SNAP and other child nutrition benefits. It increased SNAP benefits by 15 percent and provided federal dollars to support food banks.

- A continuing resolution that Congress passed in the Fall to keep the government running provides another $8 billion for child nutrition programs

- The CARES Act provided $18.5 billion toward SNAP and $8.8 billion for child nutrition programs.

Student-Based Health Care

With many schools still shuttered, millions of students have lost access to an important source of health care. As school districts and health providers cobble together solutions, Congressional funding and new regulatory flexibility could deliver some needed support.

A key source of funding for the school-based health care is Medicaid, which covers 37 percent of school-age children and reimburses $4 billion to $5 billion in services at schools annually. That figure has increased in recent years after a 2014 regulatory change allowed schools to seek reimbursement for services provided to all eligible children.

The Families First Act temporarily increases the federal match to states for Medicaid. To receive those extra dollars, states must commit to maintain current eligibility standards and premiums and to limit disenrollment. The American Rescue Plan provides incentives for more states to expand Medicaid to low-income adults, expansions that have led to more students being enrolled in other states. In addition, the stimulus plan created more affordable insurance option through state marketplaces.

Read More: How the Health and Education Sectors Can Collaborate]

Beyond legislative efforts, federal authorities are granting wide latitude on billing Medicaid for using telehealth to deliver services and urging states to expand offerings. This allows students to receive special education services or visit health providers virtually, using a smart phone or computers, without risking a visit to an office or hospital.

State Medicaid programs can reimburse these providers for telehealth services just as they do for in-person visits without obtaining federal approval, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) explained in a recent release. That said, some states have restrictions on what services must be delivered in person, especially for students with disabilities.

The legislation passed so far will hardly be Congress’s last word on education funding. Members of Congress and education leaders are already contemplating how to support K-12 schools in future stimulus bills.

[Read More: Tracking State Legislation on the Coronavirus]

CARES Act Allocation

The CARES Act requires that at least 90 percent of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund flow to local education agencies, with no more than 10 percent reserved for the state agency, and a fraction of that for administrative costs. The totals in the chart below are rounded.

| State | Total for School Relief | Minimum for LEA | Maximum for SEA | Maximum for Administration | Total for Governors Fund |

| U.S. | 13.2 B | 11.9 B | 1.3 B | 66 M | 2.9 B |

| Alabama | 217 M | 195 M | 22 M | 1 M | 49 M |

| Alaska | 38 M | 35 M | 3.8 M | 192,000 | 6.5 M |

| Arizona | 227 M | 249 B | 27 M | 1.3 M | 69 M |

| Arkansas | 129 M | 116 M | 13 M | 643,800 | 31 M |

| California | 1.6 B | 1.5 B | 165 M | 8.2 M | 355 M |

| Colorado | 121 M | 109 M | 12 M | 604,900 | 44 M |

| Connecticut | 111 M | 100 M | 11 M | 555,300 | 27 M |

| Delaware | 43 M | 39 M | 4.3 M | 217,500 | 7.9 M |

| D.C. | 42 M | 38 M | 4.2 M | 210,000 | 5.8 M |

| Florida | 770 M | 693 M | 77 M | 3.9 M | 174 M |

| Georgia | 457 M | 411 M | 46 M | 2.3 M | 106 M |

| Hawaii | 43 M | 39 M | 4.3 M | 216,900 | 9.9 M |

| Idaho | 48 M | 43 M | 4.8 M | 239,300 | 15.7 M |

| Illinois | 569 M | 513 M | 57 M | 2.8 M | 108 M |

| Indiana | 214 M | 193 M | 21 M | 1 M | 61 M |

| Iowa | 72 M | 64 M | 7.1 M | 358,100 | 26 M |

| Kansas | 85 M | 76 M | 8.4 M | 422,600 | 26 M |

| Kentucky | 193 M | 174 M | 19 M | 965,000 | 44 M |

| Louisiana | 287 M | 258 M | 29 M | 1.4 M | 50 M |

| Maine | 44 M | 39 M | 4.3 M | 218,900 | 9.3 M |

| Maryland | 208 M | 187 M | 21 M | 1 M | 46 M |

| Massachusetts | 215 M | 193 M | 21 M | 1 M | 51 M |

| Michigan | 390 M | 351 M | 39 M | 1.9 M | 89 M |

| Minnesota | 140 M | 126 M | 14 M | 700,700 | 43 M |

| Mississippi | 170 M | 153 M | 17 M | 849,400 | 35 M |

| Missouri | 208 M | 187 M | 20 M | 1 M | 55 M |

| Montana | 41 M | 37 M | 4.1 M | 206,500 | 8.8 M |

| Nebraska | 65 M | 59 M | 6.5 M | 325,400 | 16 M |

| Nevada | 117 M | 105 M | 12 M | 585,900 | 26 M |

| New Hampshire | 38 M | 34 M | 3.8 M | 188,200 | 8.9 M |

| New Jersey | 310 M | 279 M | 31 M | 1.5 M | 69 M |

| New Mexico | 109 M | 98 M | 11 M | 542,900 | 22 M |

| New York | 1 B | 933 M | 104 M | 5.2 M | 164 M |

| North Carolina | 396 M | 357 M | 40 M | 1.9 M | 96 M |

| North Dakota | 33 M | 30 M | 3.3 M | 166,500 | 5.9 M |

| Ohio | 489 M | 440 M | 49 M | 2.4 M | 105 M |

| Oklahoma | 161 M | 145 M | 16 M | 804,800 | 39 M |

| Oregon | 121 M | 108 M | 12.1 M | 605,500 | 33 M |

| Pennsylvania | 524 M | 471 M | 52 M | 2.6 M | 104 M |

| Rhode Island | 46 M | 42 M | 4.6 M | 231,800 | 8.7 M |

| South Carolina | 216 M | 195 M | 22 M | 1 M | 49 M |

| South Dakota | 41 M | 37 M | 4.1 M | 206,500 | 7.9 M |

| Tennessee | 260 M | 234 M | 26 M | 1.3 M | 64 M |

| Texas | 1.3 B | 1.1 B | 129 M | 6.4 M | 307 M |

| Utah | 68 M | 61 M | 6.8 M | 339,100 | 29 M |

| Vermont | 31 M | 28 M | 3 M | 155,700 | 4.5 M |

| Virginia | 239 M | 215 M | 24 M | 1.2 M | 67 M |

| Washington | 217 M | 195 M | 22 M | 1 M | 57 M |

| West Virginia | 86 M | 77 M | 8.6 M | 433,200 | 16 M |

| Wisconsin | 175 M | 157 M | 17 M | 873,900 | 47 M |

| Wyoming | 33 M | 29 M | 3.3 M | 162,800 | 4.7 M |

| Puerto Rico | 349 M | 314 M | 35 M | 1.7 | 47 M |