Leilah Babirye is describing what it’s like to go on a pride march in her native Uganda. “It never ends peacefully,” she says, laughing grimly. “It’s always police raids, everybody scattering.” The artist and LGBTQ+ activist made costumes for one event in 2012, including masks for friends too frightened to show their faces. “But as soon as we step on to the beach, there’s police everywhere. So we have to go back home.”

Babirye talks to me over Zoom from the place where she spends most of her time: her basement studio in Brooklyn. It’s populated by her artworks: boldly coloured, sensuous paintings of imaginary heroes; giant ceramic sculptures of faces glazed in jewel-like shades; and her signature pieces, chiselled wooden figures a bit like totem poles, lovingly painted and buffed, decorated with objects Babirye has found in the street ranging from bike chains to an old chandelier. They are bold (as tall as 15ft), idiosyncratic, and full of personality. She points her camera at one, which she hopes is heading to a prestigious New York museum.

More work can currently be seen in two locations in the UK. Babirye has a green and cream ceramic head in the biennale rounding off Coventry’s year of culture; meanwhile a nine-foot figure will preside over the London flagship store of fashion house Celine, commissioned by its creative director Hedi Slimane, the first work Babirye has ever made to order. “I wanted it to be very simple,” says Babirye. “I just put a little bit of sheet around it – and it’s the first piece where I didn’t attach wooden ears. I just used metal.” With closed eyes, a strong nose, and chain and rope hanging from head to toe, the sculpture radiates gentleness and peace.

Babirye was born in 1985 and brought up in Kampala, the capital of Uganda, a nation where gay sex carries a life sentence, public attitudes are overwhelmingly hostile, and LGBTQ+ activism is illegal: “You can be in prison if you’re even caught with a person talking about gay issues.” Not that this stopped Babirye, a lesbian active in the underground LGBTQ+ (known in Ugandan as “kuchu”) scene. In a clandestine gay bar, she says, “you have a back door so if you hear that police are coming you all rush out. We always knew how to get away.”

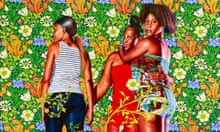

By 2015, however, Babirye was running out of options. She had been outed in Uganda’s virulently homophobic press, and when she told her tutors on her masters course at Makerere University that she wanted to explore her sexuality in her art, they refused to supervise her. A working artist by then, she applied for residencies in the UK, Sweden and the US, and got one in Fire Island, the gay holiday enclave 60 miles from New York. The artist Kehinde Wiley paid for her ticket. “By then I wasn’t talking to my father any more, so it didn’t make any sense going back home after the residency,” says Babirye, whose family have since disowned her. Do they know she’s a successful artist? “I don’t know, probably they’re watching somewhere. I don’t bother looking for them.”

Babirye applied for asylum in the US, got it in 2018, and has lived in New York ever since. She tells me she works five days a week, and takes weekends off to watch TV (her current favourites are Queen of the South and “Squid”). She says she hasn’t got many friends – “People here are a little bit crazy” – and avoids going to other art shows. “There’s a lot of artwork in New York and a lot of galleries. I don’t want it to get into my mind – it’s a lot.”

Like all her sculptures, the Celine piece carries the name of a Ugandan clan – in this case the crested crane. There are 52, named after “animals, plants, mountains, objects”. Babirye is from the antelope clan. The point is, she explains, that every LGBTQ+ person in Uganda has been given a clan name at birth – and even if those clans disown them, they still can’t take away their names. In other words, her sculptures represent Uganda’s queer community, who continue to be born, exist and aren’t going anywhere, no matter how much they’re persecuted.

There’s an irony Babirye relishes in showing her work in the UK. Before the British colonised Uganda in 1894, bringing Victorian Christianity with them, no one cared about same-sex activity. Even King Mwanga II, who was ruling before the British protectorate, was bisexual. It’s tempting to think that Babirye’s work alludes to a pre-colonial, indigenous Ugandan sculptural tradition, but she says there isn’t one: “The only sculptures we have are just ceramic ware for cooking, or spears for fighting wars.” The masks, meanwhile, are a West African thing (Uganda is in the east) used in her work to nod to those friends forced to hide behind them, for fear of hostile exposure. “You’re always running, trying to be safe,” she says of her life being a lesbian in her home nation.

An expert with a chisel, Babirye aspires to make sculptures from the wood of the jacaranda tree, as she says it’s the best to carve with, but her sculptures are mainly made from pine bought from New York lumber yards, usually used in building construction. “You don’t want to tell them you’re an artist,” she says, “or they’ll increase the price.”

The fact that such imposing sculptures have been made from lumber and scrap is significant. Queer people are often referred to in Uganda as “ebisiyaga”, the husk of a sugarcane – in other words, worthless rubbish. With her magnificent monuments to Uganda’s hidden LGBTQ+ community, Babirye shows that trash can have power, and be beautiful.

Leilah Babirye’s sculptures are at Celine, 40 New Bond Street, London, and Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry.